(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When they’re not busy bemoaning a shambolic Brexit, Brits now have another embarrassment to lament. London’s 17.6 billion pound ($22 billion) Crossrail project was meant to open this month, but it won’t.

On Monday, London’s authorities confirmed that the railway connecting Heathrow Airport in the west with Canary Wharf in the east will need up to 2 billion pounds more funding (lifting it from the 15 billion pounds or so initially expected). An already revised autumn 2019 opening date might not be met. Critics have branded Crossrail’s missteps as a “catastrophe” and a “shambles.” The project’s chairman, Sir Terry Morgan, has stepped down. But is Europe’s biggest construction project really such a big failure? So far, it’s not even close.

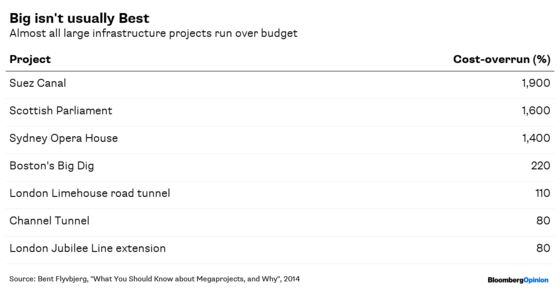

Railways, airports, bridges and concert halls, often costing upward of a billion dollars, are so frequently tardy and financially disappointing that academics say they obey an iron law: “Over budget, over time, under benefits, over and over again,” is how Oxford academic Bent Flyvbjerg puts it. With some justification. The probability of cost overruns on these ventures is about 90 percent. That doesn’t mean we should just give up on major building plans, though.

Of course, big infrastructure projects provide plenty of fodder for the cynics. Modern regulatory and planning systems mean slowness is preordained, while construction can be hugely expensive partly because of low productivity and rent-seeking. Rail projects typically cost 40 percent more than budgeted, according to Flyvbjerg, while dams tend to cost about twice as much as planned. Sometimes even that feels like a bargain.

Consider Berlin’s new international airport — BER — which was meant to open in 2012 but won’t start handling passengers until 2020. Costs first estimated at 2 billion euros have ballooned to more than 7 billion euros. Germany, whose international reputation for precision and efficiency is sometimes baffling to those of us who live here, shows that Britain’s struggles with expensive infrastructure are hardly unique.

A list of recent German white elephants include the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie concert hall, Stuttgart railway station and the BND intelligence agency headquarters. In the U.S., Boston’s Big Dig tunnel program surely merits a place in the mega-project hall of infamy.

By comparison, Crossrail’s problems — the ones we know about, at least — appear manageable. So far the total budget has risen 11 percent compared to the target agreed a decade ago. That’s no small feat in view of its engineering complexity and the number of stakeholders involved. Since tunneling started in 2012, eight giant boring machines have dug 42 kilometers (26 miles) of new rail tunnels up to 40 meters below the capital. Engineers have also almost completed 10 new stations in one of Europe’s mostly densely populated areas, yet kept business disruption to a minimum.

Digging the tunnel turned out to be the easy bit. Getting trains to recognize three different signalling systems along the route has been more trying, and testing hasn’t been completed. That’s not so unusual. A mega-project’s “uniqueness” is often what causes it to run into trouble because engineers can’t copy what they’ve done before. Seemingly run-of-the-mill details can end up derailing the whole thing. At BER, a poorly designed fire safety system was the chief problem.

Smaller, less sexy public works are often safer financially than those that win architecture prizes or set records. The same’s true for the private sector, where Airbus SE and Boeing Co. have learned that incremental innovation — giving existing aircraft new engines — is less perilous than massive clean-sheet projects such as the A380 and 787.

Still, while it would be unwise to rule out further delays and cost-overruns at Crossrail, it would be a pity if its missteps became another nail in the coffin of ambitious infrastructure investment. Eurotunnel’s investors probably regret that France and Britain built a crossing under the English Channel; the construction costs were 80 percent over budget. But the rest of us are glad it exists. Ditto, the Sydney Opera House, which cost 1,400 percent more than it should have and was worth every cent.

Rather than shrinking from grand dreams, we should learn from the mistakes. Flyvbjerg recommends breaking up large projects into less risky chunks. Being transparent about costs, and any overruns, is essential to preserve public trust. The shaky-looking case for a high-speed rail link connecting London with Birmingham and Manchester has, for example, been undermined by claims it could end up costing double the already eye-watering forecast of 56 billion pounds.

If we’re to meet the expectations of the planet’s 7.6 billion inhabitants while curtailing and adapting to climate change, we’ll need trillions of dollars more infrastructure this century. And some of it will have to be big. Crossrail shows that with political will and ample capital, humans can do pretty extraordinary things. Sadly, though, it’s usually not as quick or cheap as we might wish.

The "funding envelope" has now increased to17.6 billion pounds. In 2007 it was estimated at 15.9 billion but in 2010 this was lowered to 14.8 billion pounds. Later it was revised upwards again.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.