Lloyd Blankfein Leaves $40 Million on the Table

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Lloyd Blankfein, who is exiting the CEO suite at Goldman Sachs this week, once called the performance targets in his compensation agreements “hardly aspirational.”

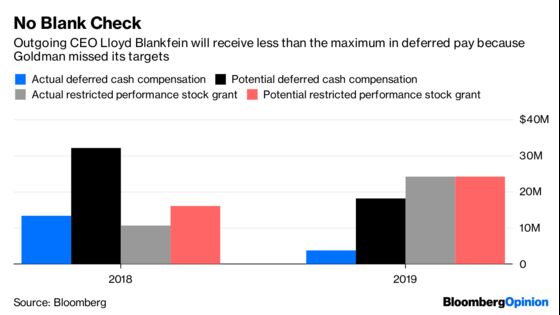

It turns out they were tougher than he thought. When Blankfein departs, he will miss out on at least $40 million, and possibly much more, in deferred compensation, the majority in cash, because he did not achieve those targets, underscoring the bank’s recent struggles and how badly he misjudged opportunities for the firm.

Most of the lost potential pay dates to 2011, when Goldman put in place what became a rolling eight-year incentive plan. The first payment is scheduled early next year. The amount that Blankfein will be ineligible to collect will most likely grow over the next few years as his deferred compensation agreements mature, which could take until 2024.

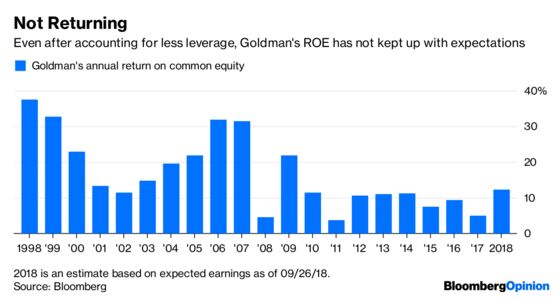

Nonetheless, Goldman has struggled to hit the original goal of 10 percent ROE, let alone the revised 12 percent. Since 2011, Goldman’s annual ROE has topped 10 percent just three times. The highest it reached was 11.2 percent in 2014, though the firm is expected to top 12 percent this year for the first time since 2009. Still, even if it does, Goldman’s ROE over the past eight years would average only 9 percent, short of what would appear to be needed for Blankfein to collect his long-term bonus payout. Blankfein’s compensation agreement, however, allows the board to calculate an adjusted ROE, excluding what it calls non-operating expenses to determine executives’ bonuses. Goldman doesn’t disclose those adjustments or what that adjusted ROE is.

At the very least, though, Goldman is likely to exclude charges related to last year’s tax law changes. It is also likely to exclude the $3 billion it paid to the government in 2015 to settle charges related to mortgage fraud in the run-up to the financial crisis, which amazingly Goldman says it can ignore when making compensation decisions for its top executives. Exclude those two items, and Goldman’s ROE increases to 10.3 percent, enough for Blankfein to earn a long-term bonus but below the 15 percent that would be needed to earn the maximum. (I shared my calculations of what Blankfein could have made, and what he likely will receive, under the long-term incentive plan with Goldman; the firm declined to comment.)

ROE tends to be a closely watched metric on Wall Street. While Goldman’s ROE has risen lately, so have the returns of its competitors. JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s ROE is expected to reach 13.5 percent this year. By next year, Goldman’s ROE is expected to fall behind both JPMorgan’s and Morgan Stanley’s.

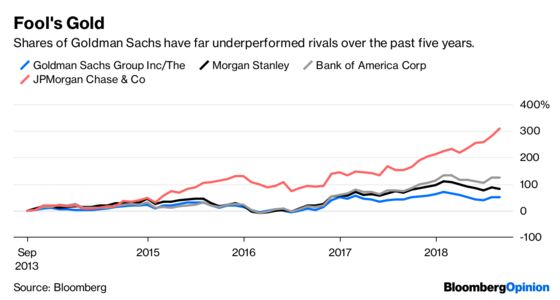

Blankfein’s compensation was also based on the firm increasing its book value per share by an annual average of 7 percent, which it didn’t do. Goldman’s shares have also far underperformed those of Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan and Morgan Stanley during the past five years, though that metric is not part of the compensation plan.

Goldman scrapped the 2011 long-term compensation plan six years later because the bank determined it was too complicated and lacked transparency, but Blankfein will continue to be paid under it. He could have received as much as $32 million early next year and $18 million the next year. Instead, Blankfein will likely receive just more than $13 million in January. His payment a year later will shrink to just less than $4 million. All told, factoring in restricted stock grants under a separate three-year incentive plan, Blankfein could have collected at least $90 million in deferred pay over the next two years. Instead, his payout will likely be just more than $50 million.

Still, $50 million is a lot of money, and the fact that Blankfein will get that much, on top of the other compensation he has received over the years — he’s a billionaire, according to Bloomberg’s calculations — is just another sign of the heads-I-win, tails-you-lose compensation scheme on Wall Street. David Solomon, who takes over as Goldman’s CEO on Monday, has already started to make changes, replacing a number of top executives and seemingly reorienting the firm toward investment banking and away from trading. But if Solomon wants to make a real change at Goldman, and indeed the rest of Wall Street, reconsidering its pay practices would be a good place to start.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Stephen Gandel is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and equity markets. He was previously a deputy digital editor for Fortune and an economics blogger at Time. He has also covered finance and the housing market.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.