Sanjeev Gupta and Greensill Became Their Own Worst Enemies

Their shared financial woes illustrate the danger of relying too heavily on one key client or funding relationship.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Greensill Capital filed for insolvency this week and its biggest client, steel magnate Sanjeev Gupta’s GFG Alliance, is scrambling to avoid a similar fate. A relationship that benefited both firms has been torn asunder. Greensill has stopped funding GFG, and the metals conglomerate has in turn defaulted on monies owed to the London-based finance firm.

Their shared financial woes illustrate the danger of relying too heavily on one key client or funding relationship. They also underscore the riskiness and opacity of the type of financing both embraced: short-term invoice-based lending.

With Greensill’s help, GFG was able to piece together a globe-spanning network of steel, aluminum and energy assets with $20 billion in annual revenue and 35,000 employees. Gupta reinvigorated unloved industrial sites and promised to lower their carbon footprint, which is admirable. But he’s taken substantial risks, in particular by not obtaining sufficiently diverse and long-term sources of finance.

Losing the Greensill cash spigot threatens to do to GFG what the loss of credit insurance did to Greensill. A February letter from GFG cited in Greensill’s U.K. insolvency filing warned that if Greensill ceased to provide working-capital finance to GFG, the latter would also “collapse into insolvency.”

GFG now says it has adequate funding for its current needs, while acknowledging that Greensill’s demise has created a “challenging situation.” It is busy, however, trying to secure alternative long-term finance. That won’t be straightforward because of the esoteric nature of its existing loans. GFG declined to comment for this column.

Greensill’s core business of invoice-based lending — where it arranges for early payment of a client’s suppliers at a discount and receives the full amount from the client later — makes very low profit margins. There’s fierce competition from big banks for blue-chip businesses, which forced Greensill to embrace riskier customers to seek better returns.

Non-investment grade companies contribute 90% of Greensill’s revenues, and of these GFG was the largest, court documents show. For a time Gupta was even a Greensill shareholder. The finance firm has about $5 billion in exposure to GFG, Bloomberg News has reported.

Diligent news reporting about these deep ties prompted GFG to pledge greater transparency and a more balanced capital structure. There was talk of public listings for its Liberty Steel, Alvance (aluminum) and SIMEC (energy) assets. “Whether it’s the steel, aluminum or energy companies ... all the companies will be made ready in terms of governance, reporting and transparency, so they’ll be ready in every way to go for a listing as and when they want to,” Gupta told Reuters in October.

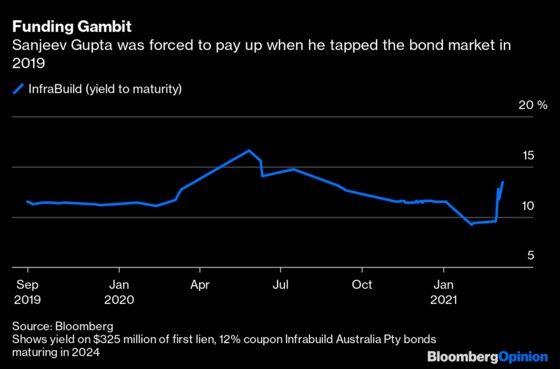

However, Liberty Steel still hasn’t published the group accounts it promised and GFG hasn't made much visible progress in tapping the capital markets, other than a poorly received junk bond.

The financing provided by Greensill to Gupta was often pretty unusual. One analyst slide deck describes how the firm helped him buy a Scottish aluminum smelter from Rio Tinto Plc by securitizing 25-years of future payment flows owed by the smelter to a hydropower plant.

Gupta was able to acquire both the power plant and the smelter while injecting little of his own cash upfront. The deal’s structure was underpinned by a Scottish government guarantee, allowing the payment promises to be packaged into bond-like securities and sold to investors, including Switzerland’s GAM Holding AG. (These illiquid assets were among those that contributed to the ouster of GAM fund manager Tim Haywood.)

Greensill also provided day-to-day invoice financing for GFG’s metals assets. Remarkably, this included funding for steel GFG hadn’t made or sold yet.

GFG has become increasingly reliant on Greensill’s “future accounts receivable” finance program where the latter provided funding against expected future invoices, Greensill’s insolvency filing states. As long as GFG could show a customer purchase agreement, Greensill had no qualms about extending credit. This effectively pulled forward those future cash flows so GFG could make use of them today. “Nothing wrong in funding from receivables. They are a safe mode,” Gupta told an Indian newspaper last year.

Arranging such borrowing was doubtless much more profitable for Greensill than its plain-vanilla business but it led to big problems. A special audit by Germany’s banking supervisor, BaFin, was unable to find evidence for some of the future receivables. Greensill’s German bank has been shuttered. Greensill said it received extensive legal advice on the accounting and complied immediately when BaFin objected.

Selling these future receivables will also leave a hole in GFG’s finances now that the funding tap has been turned off. I’ve written before about how the sudden withdrawal of invoice-based lending can exacerbate cash flow problems. Anxious suppliers demanding shorter payment terms can compound these issues.

Greensill creditors also have security over certain Gupta assets in the event GFG doesn’t honor its agreements, as does the Scottish government. All this could hamper GFG’s efforts to secure alternative finance. Gupta-related assets aren’t expected to be included in any sale of what’s left of Greensill’s firm. GFG is attempting to secure a debt standstill on the money it owes Greensill and has hired PJT Partners Inc. and Alvarez & Marsal Inc. to advise on plugging the financing gap, Bloomberg reported this week.

Only last month Gupta was still trying to enlarge his steel empire even further. ThyssenKrupp AG rejected an approach from Liberty Steel for its European steel assets after German trade unions queried how the takeover would be funded.

It’s a pity others weren’t as cautious before agreeing to sell, finance or guarantee assets for Gupta. If his sprawling empire implodes, taxpayers in various countries will be left holding the bag.

Produced by an external analyst, not by Greensill or GFG.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.