Powell Fights to Walk Back Fed’s Inflation Fear

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell made an almost lawyerly case last month that the sharp pickup in U.S. inflation was temporary. Judging by the central bank’s latest decision, he hasn’t yet managed to persuade his fellow Fed officials.

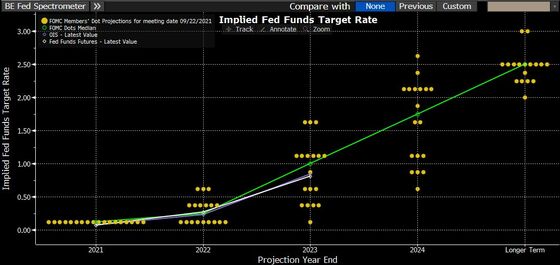

Policy makers signaled through their updated “dot plot” forecast of the fed funds rate that they’re evenly divided about whether to raise the short-term benchmark next year. That’s a shift from June, when 11 of 18 officials expected to leave it unchanged in the current range of 0% to 0.25%. What’s more, the median expectation is now for the rate to climb to 1% and 1.75% at the end of 2023 and 2024, respectively. Depending on when liftoff from the zero lower bound actually happens, that implies a tightening path that isn’t much different from the gradual pace of the last cycle, even though the Powell-led Fed has gone to great lengths to emphasize its new policy framework and its stringent requirements to raise interest rates.

The reason for this shift is straightforward: Just look at expectations for the core personal consumption expenditures price index. The median forecast among Fed officials for core PCE is 3.7% in 2021, 2.3% in 2022, 2.2% in 2023 and 2.1% in 2024. That’s not vastly higher than the central bank’s 2% target — but that’s not the criteria that the Federal Open Market Committee has described. To raise rates, as Powell has outlined countless times, inflation must reach 2% and be “on track to moderately exceed 2% for some time.” Current projections fit the bill. While “maximum employment” is less clearly defined, policy makers see the unemployment rate falling to the lowest estimate of the longer-run rate, 3.5%, by 2023 as well.

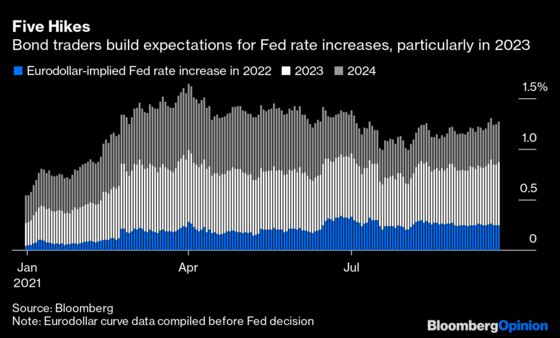

This all leans hawkish. Heading into the Fed decision, eurodollar futures were pricing in about five quarter-point interest-rate increases from now until the end of 2024. Expectations continued to climb after the decision. In the Treasury market, yields on three- and five-year notes increased while those on 10- and 30-year securities fell, flattening U.S. curves.

Powell, as is customary at his press conferences, sought to downplay any concerns about tighter policy. “Those are very modest overshoots,” he said of the inflation forecasts. “I don’t think households are going to notice a couple of tenths of an overshoot.”

That could prove to be too flippant. Inflation far in excess of 2% certainly seems to be influencing Americans’ views on price growth. As I noted last week, the New York Fed’s August survey of consumer expectations showed the median expected inflation rate over the next three years — that is to say, through mid-2024 — is 4%, the highest ever in data going back to 2013. The outlook over the next year is for crucial categories such as rent, medical costs and gasoline to increase in price by more than 9%. Powell was directly asked about this survey and mostly downplayed it.

Of course, Powell may have it right. In his speech at the Jackson Hole economic policy symposium, he highlighted the lack of broad-based inflation pressure as well as moderating price growth in goods such as used cars, sweeping measures of wage growth not yet overheating and the general global disinflationary forces over the past 25 years as reasons to expect a reversion back to modest inflation. Consistent with this, the Fed’s unanimous policy statement says elevated price growth is “largely reflecting transitory factors.”

Still, the dot plot is so firmly hawkish that it made the central bank’s move closer to reducing its $120 billion of monthly bond purchases something of an afterthought. “If progress continues broadly as expected, the Committee judges that a moderation in the pace of asset purchases may soon be warranted,” the statement said. The word “soon” is often code for “next meeting,” and, indeed, Powell made clear that all he’d need to see is a “decent employment report” for September to get him to the point at which he’d be ready to start tapering in November. He added that the process could end by the middle of next year.

After the Fed’s meeting in June, I questioned why bond traders care so much about the dot plot, given that the central bank’s new framework purportedly uses outcome-based decisions. It’s possible — and perhaps even likely, judging by the last cycle — that officials are too quick to start penciling in interest-rate increases.

For now, it’s hard to read the move higher in the dot plot as anything other than many policy makers acknowledging the risk that they could be wrong about inflation reverting back to form. If it does, then Fed officials will again look too eager to tighten. If this period of price growth is longer-lasting, however, the dots might not be quite as useless as they seem.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.