Jeffrey Vinik Thinks He Can Beat the Stock-Picking Bots

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Stock pickers are striking back.

Jeffrey Vinik, who rose to fame as manager of the Fidelity Magellan Fund in the 1990s, told CNBC last week that he was getting back into the stock-picking game. He will resurrect Vinik Asset Management, a hedge fund he closed in 2013.

Only this time, Vinik won’t just be competing with the market and other managers. He will also have to outmaneuver the computers that are increasingly displacing stock pickers.

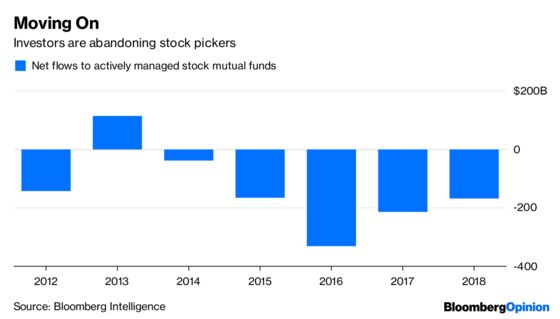

It’s a brave move. Stock pickers have struggled to perform in recent years and investors are abandoning them. Actively managed stock mutual funds have experienced net outflows for five consecutive years, a total of $918 billion from 2014 to 2018, according to estimates compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence. Hedge funds managed to hang on to their assets for most of that period, but after a disappointing 2018, investors are pulling money from them, too.

While others bemoan a profession in decline, Vinik sees a resurgence. “I think this is an incredible opportunity for old-fashioned stock picking,” Vinik told CNBC. “We’ve had decades, maybe 10 or 20 years, of active managers underperforming passive managers.”

It’s fashionable to blame a bad environment for stock picking for active managers’ woes, but it’s not entirely true. Sure, value investing has lagged the broad market over the last decade, but other styles of active management, such as growth, quality, momentum and low volatility, have beaten the market. In other words, active managers have underperformed, not active management.

In fact, Vinik’s self-described style of stock picking, “growth at a reasonable price,” has been among the winners. The MSCI USA Prime Value Index, a collection of high-quality, low-valuation stocks, has outpaced the S&P 500 Index by 0.3 percentage points a year over the last 10 years through 2018, including dividends, and by 2.9 percentage points over the last 20 years. Those numbers belie the notion that Vinik’s style of investing has been out of favor and thus ripe for a comeback.

But Vinik faces an even bigger challenge: Investors no longer need a stock picker to invest in his style of stock picking. They have many more options today than they did in the 1990s. Back then, investors had a choice between broad-market index funds, such as an S&P 500 fund, and actively managed funds; there were few other alternatives. Now, there’s an index for nearly every style of investing and lots of low-cost index funds that track them.

The difficulty for stock pickers is not only that they must now compete with robots offering similar strategies for a fraction of the price, it’s that indexes allow investors to better gauge whether managers are delivering the returns achievable from their style of investing.

Had those options existed when Vinik led the Magellan fund, he most likely would have faced greater competition, or at least more scrutiny. The numbers for the MSCI index don’t stretch back to the beginning of Vinik’s tenure at Magellan, but according to numbers compiled by Dartmouth professor Kenneth French, an equal-weighted assortment of high-profitability, low-valuation stocks would have returned a whopping 32.6 percent a year from July 1992 to May 1996, almost double the 16.9 percent a year Vinik achieved during his time at Magellan. And the risk, as measured by annualized standard deviation, would have been comparable (12.1 percent for the equal-weight portfolio and 10.2 percent for Magellan). His subsequent track record at Vinik Asset Management isn’t publicly available.

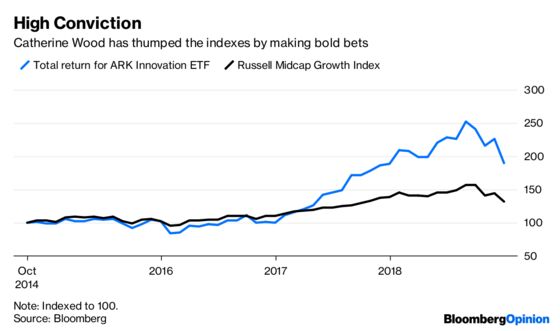

Stock pickers don’t have to play the indexes’ game, however. One thing index funds don’t do is make big, high conviction bets, and that’s where stock pickers still have an edge. Catherine Wood, manager of the ARK Innovation ETF, is doing exactly that. Just 20 stocks account for 82 percent of her fund’s holdings.

With that kind of concentration, the performance of Wood’s ETF isn’t likely to resemble an index, and it hasn’t. Wood has a penchant for high-growth U.S. mid-cap stocks, and her bets have paid off big so far. The fund returned 16.5 percent a year since November 2014 through 2018, compared with 6.8 percent for the Russell Midcap Growth Index. Her fund has also been nearly twice as volatile as the index, but that’s to be expected of a highly concentrated portfolio.

Of course, Wood’s bets could also go the other way, but win or lose, she’s in the game. It’s an example Vinik would do well to emulate when picking his growth stocks at a reasonable price. If he wants to beat the bots, he’ll have to wager big on his best ideas.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.