Japan's Labor Market Is Still Rigged Against Women

Despite a push from the government, hiring and promotions work in favor of old men and against women.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In many respects, Japan’s economy is doing better than at any time since the boom years of the 1980s. The employment rate is at all-time highs. Women have flooded into the labor force, and immigration is helping to cushion the blow of an aging society. Japanese companies, once known for low margins, are learning how to increase profits, helped by corporate-governance reforms and a burgeoning private-equity industry. The country has managed to reform some of its more dysfunctional sectors, including agriculture and retail. Exports have risen strongly, and despite an ill-advised trade war with South Korea, Japan has generally been proactive in pushing for free-trade agreements.

Despite this positive news, however, Japan isn't close to being out of the economic woods. The fundamental problem is population aging, which is putting pressure on the pension system and forcing each worker to support an increasing number of retirees. With a relatively low total fertility rate of 1.42 children per woman – 2.1 is considered replacement level – the country will need to increase productivity rapidly to stay competitive, and to keep government programs funded.

Meanwhile, despite improving gender equality in the raw employment numbers, Japan is still struggling with equality in the workplace. Despite declaring that 30% of management positions would be held by women by 2020, the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has had to content itself with only 13%. That is probably holding down both productivity – because women’s talents are being wasted -- and the fertility rate, thus compounding the country’s long-term economic challenges.

For the sake of the country’s future, Japanese corporate culture must evolve. One key change is to switch from an effort-oriented culture to a results-oriented one. Instead of monitoring how long employees are at their desks, companies should allow them to take their work home with them (which will also help them raise families while holding down jobs). A greater fraction of promotion and pay should be based on skill and results rather than seniority. A few companies are beginning to make these changes, but the trend needs to accelerate.

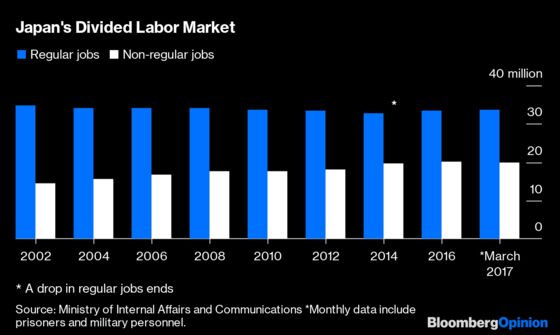

A second important step is to reform Japan’s sclerotic employment system. There now are two types of jobs – full-time jobs and contingent work. Full-time workers typically enjoy seniority-based raises and promotion, while contract and part-time workers are excluded from that track. In order to cut costs, companies have been hiring more of the latter in recent years:

Unsurprisingly, women bear the brunt of this unequal system. Of the women hired in 2018, almost three-quarters were shunted into irregular work. Fewer than half of working women hold full-time positions, compared to almost four out of five men.

This disparity is made much worse by the difficulty of switching between tracks. Traditionally, most Japanese companies hire their workers directly out of college, a system known as shukatsu. Companies have traditionally been reluctant to switch irregular workers to full-time positions, while the lifetime employment system meant that the opportunities for mid-career job switching are low. Thus, shukatsu is a high-stakes lottery -- those who fail to get the plum jobs right of college are often condemned to a much less rewarding career path, with little hope of escape. Naturally, this makes gender discrimination worse – women who were unfairly sentenced to irregular work in the shukatsu system decades ago are consigned to a dead-end track even as sexism diminishes.

The rigidity of the lifetime employment system also probably hurts productivity. Taking on a worker often means being stuck with them for decades. This makes Japanese companies overly conservative in their hiring, choosing not to gamble on potential stars who could furnish key innovations or take the business in a new direction. And seniority-based promotions install old men in upper management with limited understanding of modern business.

Fortunately, some companies are starting to change this hidebound, unfair system. Japan’s leading business group, Keidanren, recently announced that it will loosen its guidelines for shukatsu hiring. Meanwhile, job switching, though still modest, is rising. Part of that is doubtless because of a strong economy, but some is due to technology. Wantedly, a recruitment-oriented social networking site created by entrepreneur Akiko Naka, now has 2.4 million monthly active users, about 3.7% of the country’s entire labor force.

The Japanese government needs to help speed the transformation of the country’s labor markets. It should pressure companies to increase mid-career hiring, and encourage them to use services like Wantedly. Tax breaks could even be handed out to companies that hire mid-career workers. The government should also weaken legal requirements for full-time jobs and strengthen them for contract and part-time workers, in order to make companies less wary about switching employees between the two tracks.

The lifetime employment system and rigid two-track labor market served Japan well during its postwar industrialization. But it's now a liability. For the sake of both productivity and fairness, Japan needs a new labor system.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.