Is the Good Jobs Report Masking Bad News?

A statistical adjustment that missed the mark a decade ago may understate the next jobs decline. But not by much.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- To get to the July nonfarm payroll employment number that was released today — 164,000 more jobs than in June, on a seasonally adjusted basis — the Bureau of Labor Statistics had to do some major massaging and guesstimating.

There’s the seasonal adjustment, for one thing, without which the job change in July would have been negative 1.1 million. Then there’s the ominously named “birth/death adjustment,” an estimate of how many businesses have launched and shuttered, without which the not-seasonally-adjusted job loss would have been 148,000 jobs bigger. Beyond those, there’s a harder-to-quantify array of sampling techniques, aggregation methods, and other tweaks that stand between the final numbers and the raw results that the BLS gets from its monthly payroll survey of 142,000 businesses and government agencies.

The BLS makes these adjustments in an attempt to make the headline monthly payroll number an accurate gauge of how the economy is doing. Employment invariably falls from June to July as schools start their summer breaks, so a payroll number that didn’t adjust for this would be misleading. And new businesses are always being born that the BLS doesn’t yet know about and thus doesn’t survey, which is why it makes a birth/death adjustment. Any adjustment risks biasing the numbers, though, and with talk of an economic slowdown now in the air it seems like a good time to look at whether the birth/death adjustment in particular could be making the job picture look better than it really is.

The adjustment is arrived at mainly just by pretending that businesses that fail to respond to the monthly employment survey (presumably because they went out of business) never existed in the first place. This usually works because the rates of business creation and business failure tend to parallel one another. But if the economy suddenly downshifts, and far more businesses fail than are created, the birth/death model can churn out some very wrong numbers.

We know this because the BLS has another data source that it uses to fact-check its monthly payroll numbers: the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, which is based on state unemployment insurance filings by employers. The QCEW data comes out with a lag — preliminary numbers for the first quarter of 2019 will be released later this month — so the BLS uses it after the fact to make annual “benchmark revisions” of its monthly payroll numbers. The one time the birth/death model has been fully tested in a recession, the downturn of 2008-2009, these revisions showed it to have been way off.

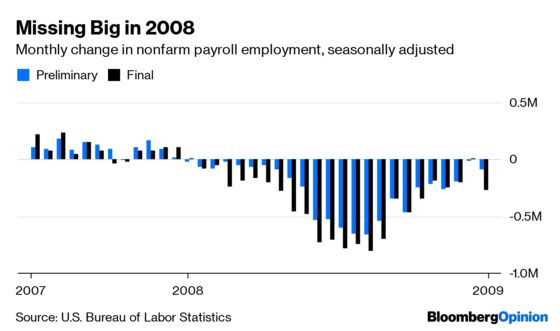

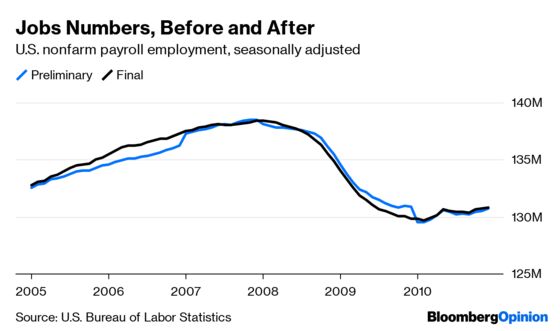

The nonfarm payroll numbers initially announced by the BLS showed much smaller job losses than were actually transpiring. The monthly revisions that the BLS makes as more survey data comes in captured some of this, then the benchmark revision released in February 2009 showed hundreds of thousands more jobs lost than had been previously reported.

People noticed. A few prescient sorts such as Barry Ritholtz, now my colleague at Bloomberg Opinion, had been warning about the birth/death model’s limitations long before, but by mid-2009 it had reached the point where bearish forecasters such as David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff were simply subtracting the birth/death adjustments that the BLS publishes every month from the employment numbers and estimating that, for example, the 345,000 reported payroll jobs loss of May 2009 was really more like 565,000. This was incorrect. Subtracting seasonally unadjusted jobs numbers from seasonally adjusted ones is a no-no in any case, and by mid-2009 the BLS was actually no longer getting things all that wrong — after benchmark revisions, the May jobs loss turned out to be … 344,000.

In 2005 and 2006, then, the BLS was understating how many payroll jobs there were. In 2008 it began overstating payroll employment. By 2010 it was pretty much spot on. I should note that even the final jobs numbers from the BLS are still estimates, with various adjustments — including some residual birth/death model effects — affecting the month-to-month changes. They’re also never really final: the BLS recently completed a “reconstruction” that affected total nonfarm payroll numbers going all the way back to when the survey started in 1939. But the difference between the preliminary numbers and post-benchmark-revision ones seems to be the best approximation we’ve got of the error in the initial numbers.

Is it possible that the birth/death adjustments have been hiding a downturn or major slowdown in payroll employment this spring and summer? Possible, yes. Probable, no. In 2007, the initial payroll numbers turned negative at the same time the revised ones did; it was only a few months into the recession that initial payroll numbers began to seriously understate matters. If the U.S. economy starts shedding jobs, the monthly payroll numbers may again understate the severity of the losses, although I’d bet the understatement would be much smaller than in 2008. That’s partly because the BLS changed its birth/death methodology in 2011 to update the model with new QCEW data quarterly instead of annually, but mainly just because the 2008-2009 recession was by most measures the worst since the Great Depression of the early 1930s. That a model based on statistical evidence that included no such occurrence failed to do its job properly is less an indictment of the model than another indication of just how bad the Great Recession of 2008-2009 was. In a shallower downturn, the birth/death model can be expected to do better.

The BLS started rolling out the birth/death model in 2000 and fully implemented it in 2003. Even before then, the agency was adjusting payroll survey data for the fact that it was missing new firms, using a less-transparent model that it simply termed “bias adjustment.” In the startup-rich 1990s it appears to have underadjusted, and thus understated job growth, which is one reason why the birth/death model was implemented. Now that the agency publishes its birth/death adjustment numbers every month, broken down by industry, it’s easy for anyone to assume that it is overadjusting, subtract out the birth/death effect and get a different jobs number. That doesn’t mean anyone necessarily should.

Unadjusted nonfarm payroll employment has fallen every July since 1951; the only other month for which this is true is January. Most of these job losses are at public schools.

The month-to-month changes in the preliminary numbers in the second chart don’t match those in the first chart because the first chart's numbers reflect the revisions that the BLS makes every month to the month-before-last’s employment total, while the second chart has all the numbers as initially reported.

This is because the BLS benchmarks the March payroll jobs numbers every year to the March QCEW numbers, then adjusts the payroll numbers for other months accordingly (using something called a "linear 'wedge-back' procedure"), rather than benchmarking every month's payroll number to every month's QCEW number. It does this because the QCEW numbers aren't perfect either, and "the benchmark revision can be more precisely interpreted as the difference between two independently derived employment counts, each subject to its own error sources." Also, the BLS examines multiple other government data sources, some of which are released with lags of as much as two years, to get at workers missed by the QCEW.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Sarah Green Carmichael at sgreencarmic@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.