Let India's ONGC Cash Grab Remain a Bad Dream

The government should buy out ONGC’s public shareholders if it wants to help itself to the oil explorer’s cash.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Here we go again. The gyrations in India’s biggest state-run oil explorer, whose stock was down more than 11.5 percent at one point last week, are a reminder that a nightmare investors thought was over might be resuming.

In early 2009, when global oil prices had collapsed from their pre-financial-crisis high, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. caused a flutter by accusing the Indian government of taking $20 billion cash from Oil & Natural Gas Corp. without consulting minority shareholders.

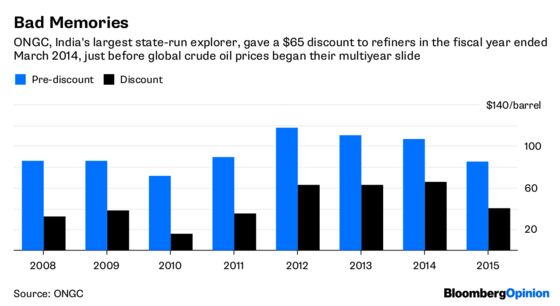

As the bank’s researchers noted, had such a raid occurred in a non-state-controlled company, it would have caused a corporate governance scandal. But with ONGC, the practice of forcing the company to sell crude oil to refiners at a subsidized price – $34 a barrel when Brent averaged $58 in the fourth quarter of 2008 – was just the way the Indian government did business.

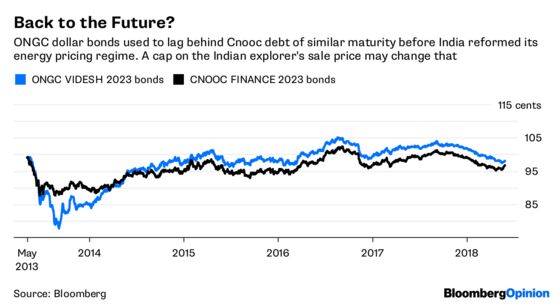

That was back then. Five years later, in early 2014, Goldman put ONGC’s bonds on its most-favored list. Whacked by the 2013 taper tantrum, India was starting to decontrol energy prices, allowing them to move more freely in line with global benchmarks. Over the following year, the discount on ONGC’s crude sales would fall from 63 percent of realizable value to 47 percent. During the fiscal year ended in March 2017, the company was able to charge full price.

How much of that was reform and how much just dumb luck? The average international price during those 12 months was only $50 a barrel, which made it easy for the government to pass it on fully to consumers. With crude now hovering around $75, there’s speculation consumers – who are already paying record-high prices for gasoline and diesel thanks to bloated federal and state taxes – will be spared further increases.

One liter of gasoline now costs more than 86 rupees ($1.28) in Mumbai, compared with an average price of 80 cents in New York. With general elections due next year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi won’t want political opponents to do to him what he did to them in 2014: channel public anger over soaring energy costs. But if he cuts taxes, an already wobbly fiscal arithmetic will go out of the window completely.

Another possibility may be to bring fuels under India’s new goods and services tax. It might have been feasible in 2015 to have a subsidy-free system with a 23 percent GST on crude oil and natural gas, as well as petroleum products. But when oil prices are high, state governments won’t agree to have their juicy ad valorem revenues subsumed by a GST.

The most convenient solution is to make ONGC share the subsidy burden once again – and then pray for Saudi-Russian output increases to lower global prices. However, as last week’s share-price reaction showed, investors don’t like the idea of a windfall tax one bit. And why should they?

The proposal that’s being discussed in the media is to saddle ONGC and other producers with a price cap of $70 a barrel.

As Bloomberg Intelligence analysts Kunal Agrawal and Lu Wang have noted, this would be “irrational, excessive and unlikely.” A windfall tax of $30 when global prices hit $100 would be almost triple China’s levy, killing investment in local oilfields and making India’s outsize dependence on imported fuel near-permanent. Worse, the tax even then would meet only half the subsidy needed to keep retail prices fixed.

Those ONGC dollar bonds that Goldman came to love tell the story. Until 2013, they lagged behind similar notes from China’s Cnooc Ltd. Subsequently, as energy pricing in India struck a reformist note, creditors' confidence in ONGC grew. Of late, though, the Indian explorer's bonds are once again losing ground. The old fears are coming back.

A price cap would be worse than the previous system of ad hoc subsidies in which the government decided from quarter to quarter what portion of the subsidy bill needed to be sent up to ONGC, and how much had to be absorbed by the refiners and taxpayers.

The explorer’s total production can’t grow too much without new investment. The only upside for ONGC investors is the price of crude. If that’s fixed, then there’s no reason to own its shares. In that case, ONGC shouldn't even be a public company.

India’s government and a clutch of state-owned companies already own 87 percent. New Delhi should buy the rest of the stock and help itself to as much of its cash as it wants. Goldman won’t complain.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.