Markets Won’t Come to the Rescue In a Brexit Crisis

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The bond vigilantes seem to have succeeded in persuading the Italian government to think again in its tussle with Brussels over next year’s budget deficit. But anyone expecting market pressure to force the U.K. Parliament to back Theresa May’s Brexit deal is likely to find the currency vigilantes are firing blanks.

Paul Donovan, chief economist at UBS Group AG’s wealth management unit, says there’s a growing consensus: The turmoil that rejecting May’s deal at its first reading would likely trigger in financial markets will force a rethink. Add the threat of the opposition Labour Party taking power, and enough of May’s colleagues should rally to support her at a second vote, Donovan argues.

But the Brexit calculations are entangled in a sort of political game theory. The U.K. Parliament has one cabal that genuinely prefers no deal to the current agreement, and a second faction that sees a rejection as the path to a second referendum that averts Brexit entirely. Neither of those sides has a motivation to concede, even at the second time of asking. Politics makes for strange bedfellows, and their combined opposition would be more than enough to torpedo May.

There’s an asymmetry in how financial markets steer government policy. Market forces can be effective in forcing administrations to abandon or amend bad policies — witness how Italian politicians pay close attention to “the gentlemen of the spread,” or how the U.K. gave up its effort to keep sterling’s value close to a target of 2.95 deutsche marks in September 1992.

But you’ll struggle to come up with examples of market reaction strong-arming politicians into adopting good policies — with the notable exception of U.S. lawmakers agreeing to give their Treasury $700 billion for its Troubled Asset Relief Program in 2008, as noted by BlackRock Inc. strategist and former U.K. government adviser Rupert Harrison.

Back then, though, the global financial markets were in meltdown. With the future of capitalism itself apparently hanging in the balance and the banking system facing an existential threat, the consequences of failing to sign TARP into law were distinct and dire. The same can be said of the European Central Bank belatedly introducing quantitative easing as surging bond yields among the euro’s peripheral members threatened the viability of the common-currency project.

Even if May’s compromise is rebuffed — increasing the possibility of the U.K. crashing out of the European Union without a deal — it’s far from certain how badly the pound would fare.

Pascal Blanque, chief investment officer at Amundi SA, Europe’s biggest fund manager with 1.5 trillion euros ($1.7 trillion) of assets, told me last week that there is zero precedent for Brexit and therefore no usable historical trading history to analyze.

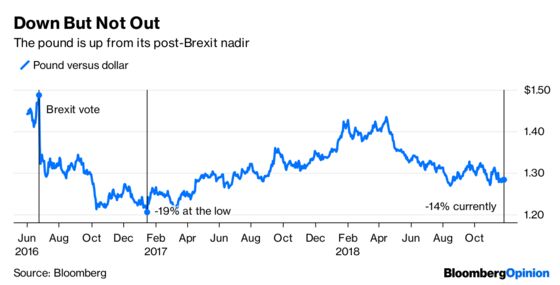

The pound is about 14 percent lower against the dollar since the Brexit referendum, up from its January 2017 nadir of about 19 percent. That 1992 episode, when the pound exited the Exchange Rate Mechanism, saw sterling falling by 14 percent against the German currency in the following three weeks. Two years later, it had lost 23 percent of its value.

The U.K.’s membership of the ERM, though, was always something of an oddity, given that the country had no intention of adopting the euro. And the rate at which the pound had been artificially maintained was so out of whack with its fundamental value that the subsequent decline was bound to overshoot.

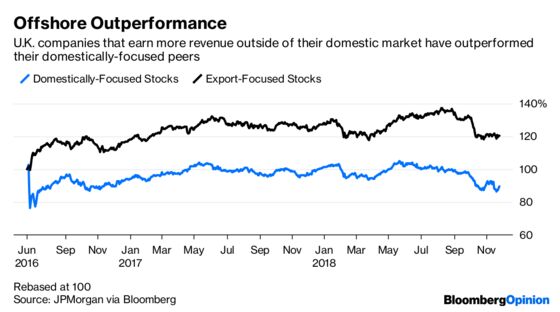

There’s a self-correcting mechanism in the currency markets that could limit sterling’s downside. The pound is both a barometer of concern about the economic implications of Brexit, and a safety valve that reduces the downward pressure on growth by boosting the fortunes of exporters.

As the pound declines, it gets cheaper for foreign investors to buy shares of U.K. companies that make the bulk of their money from selling to overseas markets. That in turn tempers sterling’s propensity to decline.

So while the U.K. currency is likely to take a hit if, as seems likely, Parliament dismisses May’s settlement, it’s far from clear that the drop would be enough to distract politicians from their domestic Machiavellian machinations. Anyone hoping that financial markets will lead to an amicable resolution of the current Brexit impasse is whistling past the graveyard.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.