Immigrants Should Do More Than Just Send Money Home

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When designing immigration policy, developed countries such as the U.S. should think not just about how to benefit themselves, but how to spur global development. For example, skilled immigrants and their children often invest in businesses in their ancestral countries, boosting economic growth and transferring technology. Sometimes they also move back. And their success often spurs developing countries to improve their education systems, in anticipation of sending more emigrants abroad. These flows of money, knowledge and people tend to create a win-win for rich and poor countries; the rich country gains skilled workers and investment returns, while the poor country gains capital, technology and opportunities for its people.

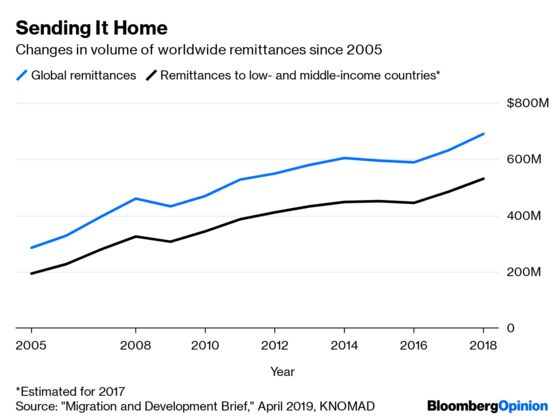

Then there are remittances. Immigrants working overseas often send money to their families back home. Given the lower prices in developing countries, these remittances can make a big impact. This type of transfer has grown in recent years:

According to a new report by the World Bank and the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development, remittances are now larger than either foreign direct investment or official development assistance to low- and middle-income countries other than China.

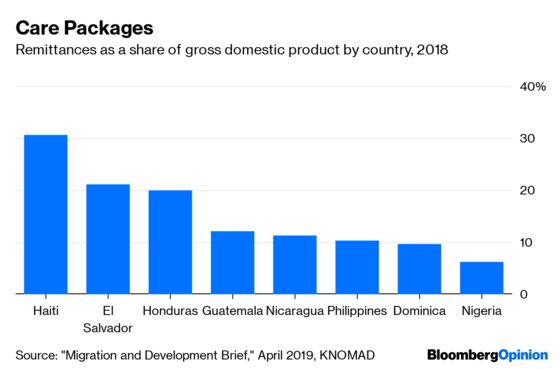

For some countries, including some in Latin America and the Caribbean, remittances represent a substantial portion of their entire national income:

It’s little wonder, therefore, that migrants from places like Honduras and El Salvador are clamoring to be let into the U.S. -- in other words, the livelihood of their families and their homelands depend on the money they send back.

This money can reduce poverty in some of the world’s poorest places, with tangible positive consequences for the quality of human life. Research shows that remittances lead to improved health outcomes and greater educational attainment for children in developing countries.

But do remittances contribute to sustainable economic growth? Here, the picture is murky; studies suggest remittances have a small effect on growth. Some researchers have found that families that receive remittances tend to work less. Others find that recipients tend to invest more, though this investment may be in the form of property speculation that does little to boost growth.

There is also the worry that countries that receive substantial remittances may come to be dependent on those flows, and thus refrain from doing the difficult and expensive work of creating valuable industries in their home economies -- a situation that bears some resemblance to the way that natural-resource wealth often holds back long-term development in poor countries.

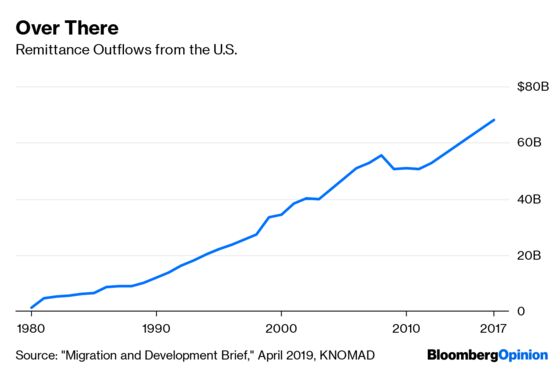

For the rich countries that are the source of remittances, there are also costs, although these are modest. For the U.S., remittances represent only a small portion of its huge, wealthy economy -- about 0.3% of gross domestic product. But that number has ballooned in the last few decades:

When immigrants spend their earnings on goods and services produced nearby -- haircuts, doctor’s appointments, legal services, rent and so on -- that spending creates jobs for locals, creating what economists call a local multiplier effect. When they invest in their home country, the returns on that investment likewise tend to get spent in the U.S. But when a worker sends money abroad, that’s money that's taken out of the local economy. This represents a modest but real loss of wealth for the U.S.

The leakage of money represented by remittances is not yet a major burden on the U.S. economy. But it does reduce the economic benefit that accrues to native-born Americans from allowing in migrants from countries like Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, and could thus fan the flames of nativist sentiment. And it probably doesn’t do much to make those countries richer, which in the long run would reduce migration pressure.

The U.S. therefore has a vested interest in encouraging immigrants to invest in their home countries rather than simply mailing money back. One way of doing this would be to tax remittances, as president Donald Trump has proposed to do. This would be a tax on the poorest of the poor, however, which doesn't seem justifiable. A more humane policy would be to give tax credits or other incentives for immigrants who invest in productive businesses in their home countries. But this would be difficult to enforce, as it’s probably not that hard to pass off remittances as business investment.

A third alternative is to have government agencies in both the U.S. and other countries coordinate to help immigrants and their families use their U.S. earnings to make productive investments back home. Not only would this produce more of a return for the U.S., it would speed economic growth in poor Central American countries, which would eventually reduce the number of migrants trying to get into the U.S.

Remittances are OK, but there’s no substitute for investment, growth and economic development.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.