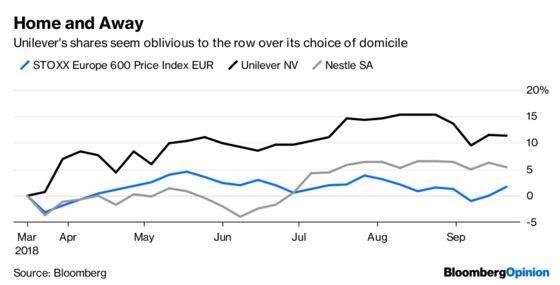

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Unilever boss Paul Polman has been conspicuously absent in the controversy over the consumer group’s plan to scrap its dual-headed structure. But the humiliation would be his if U.K. shareholders veto his plans to create a unified Dutch company. He should get ready to pay them a premium to buy their support.

To recap: Unilever’s assets are divided between separate British Plc and Dutch NV companies, each with their own class of shares. Polman wants to create a new Dutch entity that buys out both groups. There would be one company, and a single category of share that would trade in euros, pounds and dollars in Amsterdam, London and New York.

This benefits all but a handful of investment funds whose self-imposed strategy restricts them to investing client money in U.K.-domiciled or FTSE-100 companies, which Unilever would cease to be. Such institutions will have to sell their Unilever Plc stock, and at a time not of their choosing. They will also miss out on the upside from whatever the company does next: the simplification would make it much easier to attempt a big U.S. takeover or spin off the food business, for example.

The naysayers are justifiably acting in their own clients’ interests. That may not bolster their credentials as stewards of the company as a whole — but if forced to sell, they wouldn’t be able to exercise any stewardship at all. It’s also true that they consciously chose to constrain their investment freedom. Country or benchmark restrictions limit flexibility and add foreseeable risks, including that a portfolio company shifts its domicile out of the U.K. But the affected funds have a vote, and who can blame them for using it when the proposal is put to shareholders next month?

The refuseniks have a disproportionate influence over the outcome. The plan needs to be approved by a simple majority of Plc shareholders by number, with at least 75 percent of the U.K. shares being voted in favor. These twin hurdles mean Unilever cannot assume it will win the day.

There are good reasons to buy the support of the detractors. For Unilever, the simplification plan creates strategic options which have value and should, in theory, lower the group’s cost of capital. The forced sellers will receive none of that. Moreover, the uplift is arguably shared unequally between the existing NV holders and the Plc holders. The former receive a new Unilever share pretty much identical to the one they own already. The latter swap a U.K. share for a Dutch share which isn’t quite the same. The worry for them is the Dutch withholding tax on dividends: The government has promised to scrap the levy by 2020, but could always perform a U-turn.

Unilever has a get-around — a pot of up to 58 billion euros ($68 billion) of capital from which payments can be made to Plc shareholders exempt of the levy. That’s big relative to the Plc’s 1.8 billion euros of annual dividends. But it’s not infinite.

These differences in how the simplification benefits are received by NV and Plc shareholders are not captured in the current terms of the plan.

The seemingly simple solution would be for Unilever to buy back the forced sellers’ shares at a premium — a so-called off-market buyback. The snag is that this targeted favoritism may be deemed market abuse.

Plan B would be for the newly established Dutch company to make an attractive offer to buy out the Plc’s shareholders, so they end up with slightly more than their fair share of the combined operation.

The existing Dutch Unilever NV is bigger than the British Unilever Plc. Technically, Plc shareholders should own 45 percent of the new group in accordance with the two entities’ relative size. The current plan is to respect that by offering both Plc and NV shareholders one share in the new company for every one they own. If the U.K. holders were offered one-and-a-bit new shares instead, while NV shareholders still received only one, they would end up with a larger share of the new group, say, 48 percent. That would mean a small inconvenience premium would be paid by NV holders to Plc holders.

It makes sense for NV shareholders to swallow these asymmetric terms. True, Unilever’s share count would rise so earnings per share would be diluted slightly. But the cost of the premium would, at least in theory, be offset by the theoretical financial benefits of simplification.

Polman is a champion of doing the right thing. Good corporate governance means treating all investors fairly. There are principled and tactical reasons to offer compensation to the Plc crowd.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Hughes is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals. He previously worked for Reuters Breakingviews, as well as the Financial Times and the Independent newspaper.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.