No Bolt, No Problem for the Quiet Olympics

A lack of crowds will impact showmanship, but that doesn’t mean these games will be devoid of excitement.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Whoever takes the 100-meters crown from Usain Bolt will be denied the fervent victory lap in Tokyo that the now-retired reigning champ enjoyed at Rio de Janeiro in 2016. Bolt’s third-straight win in that event came in at 9.81 seconds, but the performance in front of a live audience of 60,000 in the stadium continued much longer, as he bathed in the adulation of victory. The Jamaican hero stopped for selfies and his famous lightning-bolt pose, and went on to bag the final two of his eight Olympic career gold medals.

Our next winner will also receive a gold medal — that he’ll need to hang around his neck himself — take the top of the podium, hear his national anthem, and get a line in the history books. Yet the glory will be muted. Japan’s National Stadium will be like an echo chamber, kept empty of fans to limit the spread of Covid-19. Gone will be the on-field party, and likely any victory lap — no point when there are only vacant stands to parade in front of — while replays of the race and celebration surely won’t garner 14 million views on YouTube.

With most Olympic audiences watching from home anyway (2.6 billion people in 2016), it’s easy to dismiss the importance of packed stadiums for the 100 meters — for many, the defining moment of any Games — and those who compete. But crowds matter, for events from swimming to gymnastics and football to basketball, and there’s no true replacement for that on-site excitement. But at least the track finalists, and 11,000 other athletes, will get something that was never assured: the chance to compete.

As the pandemic stretched into its second year, the International Olympics Committee and Games organizers were left with the choice of canceling altogether — never likely, given the financial and political considerations — or running the already-rescheduled event under stricter conditions. The latter was chosen, and with it came another set of decisions based on Tokyo’s own struggle to halt the spread of the virus and low rate of vaccinations. Ultimately, having any crowds at all while maintaining safety was considered unfeasible. Tokyo’s ongoing state of emergency confirmed this conclusion.

Recent events provide some comparison. This year’s Tour de France wrapped up last Sunday, with fans jamming the roads while cyclists donned masks before and after each day’s racing. The European Football Championship — like the Olympics, delayed by a year — tried mixed approaches, with some stadiums at full capacity and others limited.

With the world’s largest sporting event, though, athletes, officials and broadcasters are venturing into new territory as they seek ways to keep the excitement alive for more than two weeks amid new guidelines aimed at balancing the intimate nature of competitive sport with the public-health requirement to limit contact.

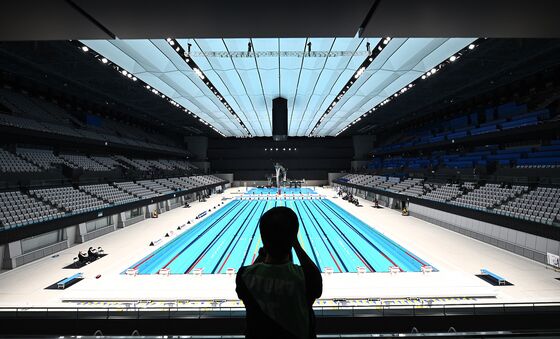

That means no chants at the swimming pool or cheers in the gymnastics arena, even by the few people allowed to be there. It heightens the concerns of muted television coverage for national broadcasters who paid more than $4 billion for rights in their markets. For the U.S., Comcast Corp.’s NBC has a strategy to tackle the silence. The broadcaster has “sound-design plans” aimed at focusing on the athletes. Rather than piping in crowd noises to generate an audience connection, similar to canned laughter in sitcoms, the plan is to feature audio of sport itself, “from the thrashing and splashing in the pool to those intimate conversations between competitors and coaches,” executives said earlier this month.

Since fans can’t get to the Games, NBC is planning a nationwide telecast to bring the Games to fans. The largest such gathering will be at its Universal Resorts in Orlando, where a two-week watch party will include the families of some athletes, while it will also likely cross to the living rooms of others to tap into the drama and capture real-time responses. Followers of the NFL draft will be familiar with this tactic to build excitement after last year’s event was held remotely, with cameras positioned at players’ homes to build tension and broadcast reactions as picks were announced.

All this might work for viewers, but won’t do much for athletes, though opinions are mixed whether performances improve or deteriorate in front of large crowds.

For those accustomed to playing off this energy — watch high and long jumpers encouraging a slow clap from the stadium — the calm might be an impediment. Yet others who usually train and race in silence can be overawed by the spectacle. There’s also evidence suggesting that crowds have an impact on refereeing decisions, often in favor of the home team or larger fan base.

One way to gauge the impact on performance would be to track how many world and Olympic records are set this time versus previous events. Similarly, tracking personal bests will help indicate whether the special conditions at Tokyo make a difference.

Crowds are only one variable. Conditions and climate also play a role while — hotter weather hurts endurance athletes, and Japan will be sweltering. We also can’t forget that most athletes have had their preparation interrupted over the last year, so any statistical approach won’t be without problems.

Tracking audiences will help show whether viewers are turned away by a lack of crowds, or may be more eager to watch due to limited alternatives at home as the pandemic drags on. Data from The Walt Disney Co.’s ESPN suggests the latter may be the case, reporting a 31% increase in audience for the recent European football tournament among U.S. audiences.

Perhaps we shouldn’t look at numbers and crowds and audience sizes. Instead, we’d be best to just revel in the spectacle of sports at their highest level. And be thankful that we’re around to watch them.

Bolt won the triple-triple: Gold in 2008, 2012 and 2016 for the 100 meters, 200 meters, and 4x100 meters, but subsequently lost the 2008 relay title when a teammate was disqualified for doping.

Defined as having watched at least 15 minutes of the event. The 1-minute reach was 3.2 billion.

More than 11,000 are listed, but the actual number who turn up may change.

Rights are sold per Winter andSummer Games cycle, with Winter Pyeongchang 2018 combined with Tokyo 2020.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tim Culpan is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. He previously covered technology for Bloomberg News.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.