Oil Isn't the Only Fuel in the Persian Gulf Firing Line

Rising tensions after tanker attacks near the Hormuz Strait threaten the liquefied natural gas trade too.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- News of more mysterious tanker attacks, this time in the Gulf of Oman, had their predictable effect on (otherwise lifeless) oil prices Thursday morning. But there’s another fuel that plies those troubled waters: liquefied natural gas, or LNG. What might conflict, or the threat of it, mean for one of the fastest growing bits of the energy business?

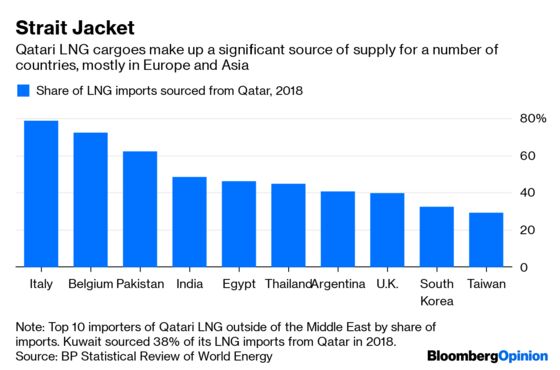

In theory, an extended conflict along the lines of the so-called tanker war of the 1980s could have a serious impact on the LNG trade. Just over 26% of all LNG cargoes passed through the Strait of Hormuz in 2018, according to data from BP Plc, close to the roughly 30% of oil flows estimated by the Energy Information Administration. Qatar accounts for the vast majority of those – and a large proportion of the imports taken by a number of countries outside the region:

Besides interdicted cargoes of LNG, the presumably similar impact on oil tankers would also drive up LNG prices, as many supply contracts are indexed to oil.

As my colleague Julian Lee writes here, outside of a broader war, Iran has little to gain from launching an all-out tanker war that would disrupt what’s left of its own sanctions-hit energy trade and would invite the destructive attention of the U.S. Navy. Even so, the threat of conflict or sporadic attacks like this could still have an impact on the LNG market.

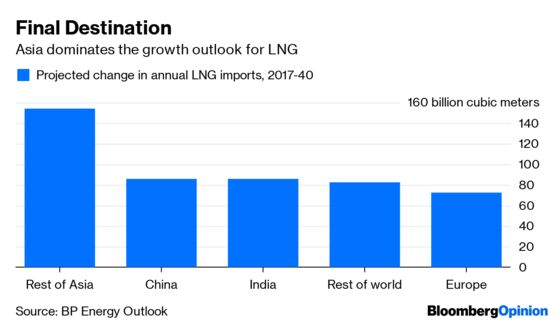

LNG is the engine driving bullishness in the global gas trade. Roughly 40% of the growth in global gas production through 2040 will involve flows moving between different regions, according to BP’s latest projections. Of that trade, LNG is expected to account for more than two thirds – and China, India and the rest of Asia dominate.

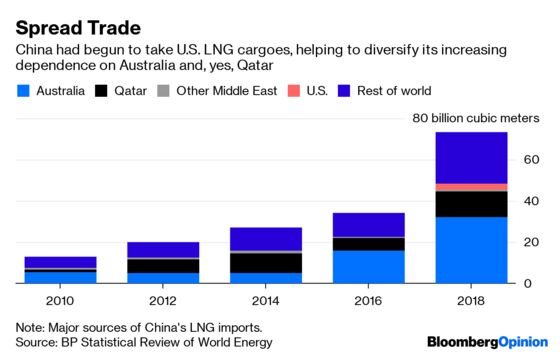

For China, rising LNG imports offer a way to curb reliance on coal and its associated pollution. From a strategic point of view, however, they represent another leg of rising energy-import dependence – for a country that wasn’t exactly thrilled about that even before it got into a trade war with the U.S. China already relies on imports to meet more than 70% of its oil demand – a higher proportion than the U.S. even at its peak dependency in 2005 – and the country satisfied about 44% of its gas demand via imports in 2018. The latter looks certain to rise on current trends.

As Stephen O’Sullivan writes in a recent report for the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, China’s import dependency for oil is mitigated by the fact that oil is more fungible and that Beijing has already stocked a large strategic reserve of it. The biggest contrast with gas, however, is timing:

The difference between rising oil import dependency and rising gas import dependency may relate, above all, to a contrast between the global political environment when China’s oil imports were initially rising strongly 10 years ago and the current political environment when the same volume growth has been true of gas. Clearly the situation is more fraught than a decade ago.

LNG has already been caught up in the trade spat, with China having imposed a tariff on U.S. LNG cargoes. This effectively closes off an important avenue for China to diversify its LNG imports, the primary means of managing increasing import dependency.

This changing environment could chill China’s appetite for more LNG cargoes – and that could reshape the energy outlook in multiple dimensions.

Most obviously, if Qatari and U.S. cargoes are less desirable, then that helps other potential suppliers. Apart from those in the region, such as Australia and Malaysia, development projects in eastern Africa could benefit, as would long-stalled plans on Canada’s Pacific coast. Argentina, with its own shale-gas sector, could also benefit, with Wood Mackenzie pointing out the country’s peak potential LNG production in the summer months would coincide with strong winter demand from utilities in Asia.

Equally, though, more piped gas from Russia and central Asia, as well as Russian LNG, would potentially look more attractive. The Power of Siberia pipeline is due to start deliveries to China soon, and strategic considerations could conceivably tip the scales on a second line. Notably, Chinese buyers have agreed to take a 20% stake in Novatek PJSC’s LNG project on Russia’s Arctic coast – a deal announced only a couple of months ago, after the tariff battle with the U.S. began.

More drastically, though, China could well decide to deal with its exposure to potentially unreliable LNG cargoes by dialing back reliance on gas in general. That could cut several ways. Renewable energy, produced domestically and bolstering China’s own industrial base, is one obvious potential beneficiary. Tempering such hopes, however, is the fact that, despite a jump in renewable-energy production in China last year, the country also accounted for 30% of the growth in global consumption of another domestic fuel source it has in abundance: coal. The same story holds for India, another fast-growing market reliant on Qatar for a lot of LNG.

Either way, this gets at the most pernicious aspect of even a simmering, rather than hot, conflict. Geopolitics might cause spikes in traded-energy prices in the near term, but tends to depress consumption over the longer term. A BP scenario released earlier this year surmised a roll-back in globalization would actually hit gas-demand growth harder than one involving a more rapid transition to lower carbon energy sources.

Yet that scenario is starting to play out already. Besides potential disruption in the Middle East, the trade war and America’s shift toward a more openly mercantile stance under the rubric of “energy dominance” represent a fundamental break with the past. Only on Wednesday, President Donald Trump threatened sanctions against Germany over the long-delayed Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which he and a sizable contingent in Congress believe would leave this nominal ally overly dependent on Russian gas. The European Union must wonder how much of this is driven by real concern for its energy security and how much owes to a desire to export more “molecules of U.S. freedom” across the Atlantic – especially as Washington’s standoff with Tehran threatens an important LNG source that mitigates Moscow’s power in the continent’s energy market.

Oil’s traditional, and varying, geopolitical risk premium is the last thing those LNG tankers should take onboard.

exports from a fourth, Yemen, havesuccumbed to war already

Oman’s own LNG facilities are further south, close to where the Gulf of Oman opens out into the Arabian Sea, so they are less exposed to attack.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.