The Hertz-Tesla Deal Will Help Normalize Electric Cars

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The first car I ever owned was electric. I had driven many regular rentals up to that point. But having lived most of my life in London and then New York, owning never appealed; both cities offered cheaper forms of masochism (I’m told). I finally took the plunge after moving to the Bay Area, leasing a BMW i3. I loved it, but gave it up for a regular gasoline car when I moved back east to the New York suburbs, needing more range.

I’ve been thinking about that i3 this past week for two reasons. First, I recently got to take Rivian Automotive Inc.’s brand new R1T electric pickup out for a test drive. Second, Bloomberg News reported Monday morning that Hertz Global Holdings Inc. has placed an order for 100,000 Tesla Inc. vehicles. What links these all together is the concept of familiarity.

The R1T has earned rave reviews. As I’m not what you would call a car person, adding mine isn’t likely to convince anyone. I can tell you the acceleration is exactly what you should expect of an electric vehicle — as in, head-snappingly rapid — but this comes with an extra helping of cognitive dissonance when you remember it’s happening in a truck weighing more than three tons.

In calmer moments, what really struck me was how things had moved on in one important respect from when I leased that i3; namely, the driver’s relationship with that all-important battery.

My i3 could go about 90 miles on a full charge and also had a range-extender, effectively a small gasoline engine used to recharge the battery and ease range-anxiety. If a vehicle can have an ethos, the i3’s was pushing range. It had three driving modes: Comfort, Eco Pro and Eco Pro+. As the names suggest, two of those were all about efficiency, automatically adjusting things like air conditioning and acceleration to squeeze more miles out of a charge. After each drive, BMW’s app would even rate your efficiency overall, which turned into something of a competitive sport with my wife.

Five years on, the very names of the R1T’s driving modes show how much has changed. All-Purpose and Conserve echo the basic objectives of the i3’s lineup. Yet there are now a host of others: Sport, Tow (it is a truck, after all) and even several Off-Road modes, including Rock Crawl. I can’t say I did much of the latter in Westchester or Rockland Counties, although even just on a gravel road you can immediately tell the difference compared with a conventional car.

The bigger point, however, is that the mindset has shifted. My old i3 was configured around easing my range anxiety. The R1T pointedly downplays the issue, instead showing off what a connected battery-powered vehicle can do. You can even buy an induction camping stove that slides out of a rather nifty through-body extra storage space called the “gear tunnel,” itself possible because electric vehicles, lacking the bulky drivetrains of conventional counterparts, have more flexibility with space.

Improving battery technology is the primary reason for this. Despite its heft, the R1T I drove is rated for more than 300 miles by the EPA, although real-world range is, as usual, bound to be less than that. As an aside, the latest version of the i3 is now rated for more than 150 miles.

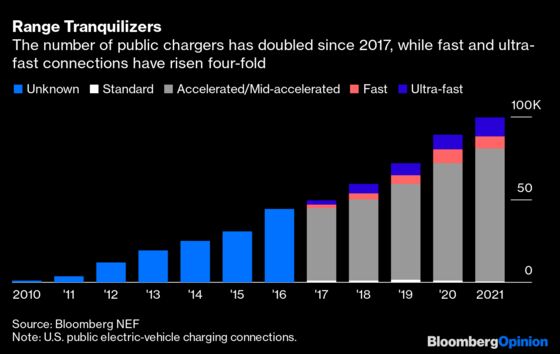

There are other reasons for the de-emphasis on range, especially the growing network of public chargers, including fast chargers that can restore even a big battery like that in an electric truck within half an hour. Charging the i3 in San Francisco back in 2016 would take about three hours. Once you factor in the dinner we had while waiting, the all-in cost per gallon equivalent makes even today’s California pump prices look ultra-cheap.

Hertz’s decision to take 100,000 Teslas fits this trend. Connected vehicles make intuitive sense for fleet companies, because of the premium experiences that can be sold to drivers and the potential maintenance benefits of remote diagnostics. EVs, however, have been challenging. Beside their hefty price tags and limited quantities, range anxiety and sheer unfamiliarity deter many drivers. And lack of a track record on how long EVs hold their value deters fleet managers, as does reliance for service on relatively untested manufacturers. Hertz first announced a global EV initiative more than a decade ago.

That Hertz is doing it again, now, and with a multi-billion-dollar commitment, is telling. Sure, coming out of bankruptcy provides a certain clean-slate freedom for bold moves. But committing this much capital to depreciating assets with which most drivers aren’t familiar is a statement that issues of range anxiety and access to charging are beginning to fade in importance, similar to my observations spanning a few short years. It may also position Hertz well with a certain, growing pool of capital — the ESG crowd — and national and sub-national governments placing more restrictions on vehicles with tailpipes or putting a future sell-by date on them altogether.

It comes with big risks. While Tesla pioneered the normalization of EVs through a mix of battery technology and design choices, service has been a sore spot. And even with longer range and more chargers, drivers can need a little hand-holding to get them comfortable with the experience, as well as EV-specific novelties like one-pedal driving. Such high-touch customer service tends to be a rare commodity in airport parking lots at 11 p.m. Still, if Hertz’s move portends wider adoption by rental companies, the familiarity it breeds would offer a cure of sorts.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.