(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have both proposed to make higher education free for all Americans. This proposal has an intuitive logic. Elementary school and high school is provided at no charge. Higher education, they argue, shouldn't be any different, especially in an economy where a post-secondary degree is increasingly required for a middle-class job.

Moreover, if higher education had always been tuition-free, students would not have accumulated so much debt. Cancelling that debt may be expensive, but maybe that’s the price the nation has to pay for neglecting its responsibility to provide higher education to anyone who wanted it.

Yet there are reasons to suspect that this narrative gets the causation backwards. What if the problem isn’t that there are too few college graduates, but that there are too many? Maybe employers needlessly demand college degrees for jobs that don’t require advanced education simply because so many people have them. And maybe the glut of college graduates can be blamed on easy government credit, specifically an increase in undergraduate federal loan limits to $27,000 in 2008 from $17,125 in 2006.

If that’s the case, free college won’t provide essential training for sophisticated jobs. It’ll just push workers into a rat-race competition for ever more onerous academic qualifications that won’t translate into rising wages.

There are two schools of thought, each with some merit, that support the suspicion that federal grant and loan policies have created a growing class of overeducated workers whose degrees won’t actually help them get high-paying jobs. The first, call it the credentialization school, is usually associated with left-of-center economists. The second, typically associated with right-of-center economists, prefers an explanation they call the signaling hypothesis.

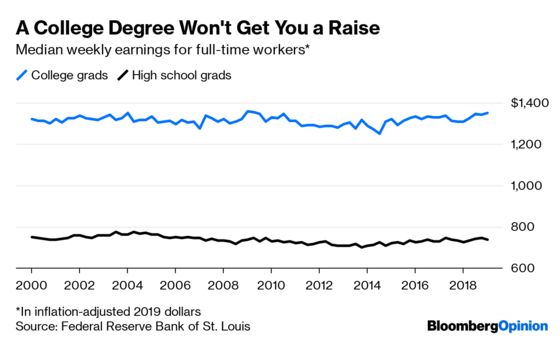

The credentialization argument begins with the observation that wages for both high school and college-educated workers have stagnated since 2000.

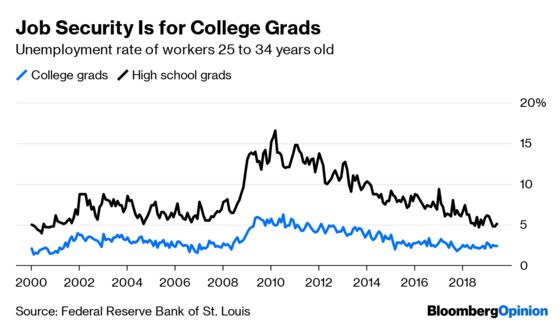

Those with only a high school education, however, have had a much harder time finding a job. Unemployment spiked far higher among young workers with only a high school education, exceeding 15% at its 2010 peak.

In addition, workers of all ages with only a high-school degree were more likely to stop looking for a job. As a result, high-school graduates were 26% less likely to be employed than college graduates in 2014.

Credentialization proponents argue that employers took advantage of the increased bargaining power the 2009 recession offered them to reduce their own training expenditures by only hiring workers with higher levels of education. The federal government misinterpreted this as a shift toward a higher-skilled economy and responded by increasing tuition aid and the maximum amount of loans that students could take out.

Colleges, in turn, responded to the increase in loans and aid by increasing tuition and lowering their own student aid funding. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that for every dollar increase in the federal subsidized loan limit, colleges raised tuition by 58 cents and lowered institutional aid by 20 cents. The result was that younger workers were saddled with higher levels of debt without the prospect of higher earnings.

The signaling argument, by contrast, focuses on the fact that most of what students learn in college is not directly applicable to their future jobs. Even students who major in science, technology, engineering and math spend most of their time taking courses outside their major.

Moreover, even the most in-demand skills, like computer programming, can be learned outside of college from vocational courses or at home from books and online tutorials. The reason students go to college, according to this view, is not chiefly to learn new skills but to signal to employers that they are smart and diligent.

Signaling proponents also point to the sheepskin effect. Workers who complete nearly all of their college course work, but for some reason don’t graduate, have earnings closer to high-school-educated workers than to those who actually obtain a degree.

If it were skills that mattered, then having taken the courses should raise a workers productivity and allow her to command a higher wage. Instead, it seems that employers place more value on the student’s ability to follow through and finish what she started.

The signaling hypothesis suggests that loans and student aid, which make college more accessible, intensify the need to go to college in the first place. In the absence of student aid and loans, many smart and hard-working young people would not be able, and in the past were not able, to afford college.

The fact that a student had completed college would be a good sign, but the fact that she only had a high school education wouldn’t necessarily be a bad one. As loans and aid increase, not having attended college becomes an increasingly bad sign. Employers who would have in the past taken a chance on someone with only a high school diploma are now reluctant to do so.

The two theories are a not mutually exclusive. Employers could be demanding higher-educated workers both as a way of lowering their own training costs and as a way to identify the more diligent applicants. In either case, however, expanding student loans was a mistake that led to higher costs and little overall improvement in young people’s opportunities.

And both theories provide good reasons to doubt the wisdom of radically increasing federal funding for college.

While both theories weaken the case for free college, they bolster the case for loan forgiveness. They suggest that the rapid increase in student debt was the result of poor policy rather than poor decision making on the part of students.

While it's becoming increasingly clear that offering students more federally financed debt was a mistake, it may not be realistic to reverse it. But the damage could be eased by freezing the caps on loan limits and encouraging employers and college endowments to take up more of the costs of training the workforce.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Karl W. Smith is a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina's school of government and founder of the blog Modeled Behavior.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.