Forget Banks and Worry About High Stock Prices

Banks shouldn’t be the biggest concern for the investors as next meltdown won’t be triggered by financial system.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s time for investors to stop fighting the last war. The next downturn most likely won’t be triggered by another meltdown of the financial system.

The Federal Reserve has concluded its stress test of big banks, a look into whether they have enough money set aside to withstand another 2008-type financial crisis. The Fed announced last week that all 35 banks examined are sufficiently capitalized. It disclosed the second and final round of results on Thursday afternoon, giving all but one bank a passing grade and the go-ahead to return money to shareholders.

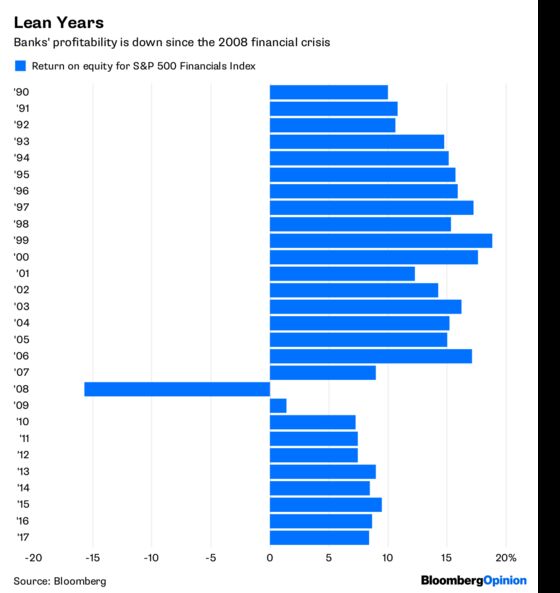

Investors didn’t need the Fed to tell them that banks are in better shape than they were a decade ago. The signs are everywhere. Profits have fallen across the industry since the financial crisis, an indication that banks are taking on less risk. Profit margins for the S&P 500 Financials Index averaged 9.3 percent from 2008 to 2017, down from an average of 13.8 percent from 2003 to 2007, the years leading up to the crisis. Return on equity is down to an average of 5.2 percent from 14.5 percent over the same periods.

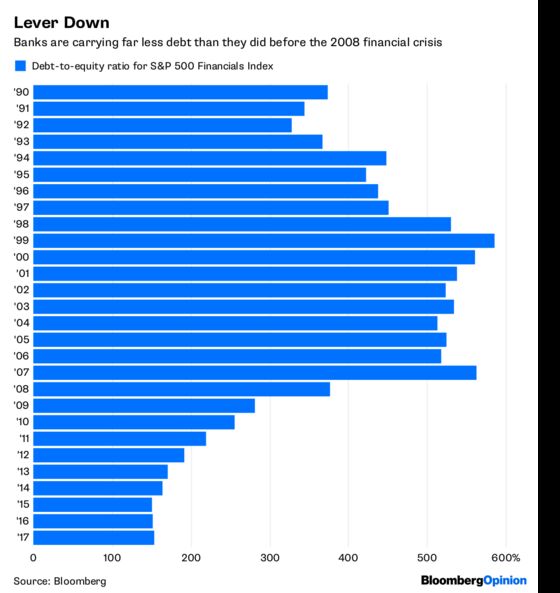

The biggest of those risks is leverage — or piling on debt to boost profits — and banks have a lot less of it than they used to. The debt-to-equity ratio of the financials index has dropped to 159 percent as of the first quarter from 563 percent at the end of 2007. The debt-to-assets ratio has fallen to 19 percent from 43 percent over the same period.

None of this is lost on the market, which has tagged financial firms with prices befitting the boring businesses they’ve become. The sector is one of the cheapest, with a price-to-earnings ratio for the financials index of 15.7 based on 12-month trailing earnings per share. That compares with a P/E ratio of 20.7 for the S&P 500 Index and 22.6 for the highflying S&P 500 Information Technology Index, a premium of 44 percent over banks.

Still, investors don’t seem comforted. The financials index was down 13 consecutive trading days through Wednesday, with the biggest declines coming after the first Fed announcement on June 21.

Many observers blame those declines on worries that an inverted yield curve and a trade war will dent banks’ profits. Sure, those are legitimate concerns, but they don’t explain why banks and why now. An inverted yield curve is no worse for banks than the environment of low interest rates and strict regulation that has existed since the financial crisis.

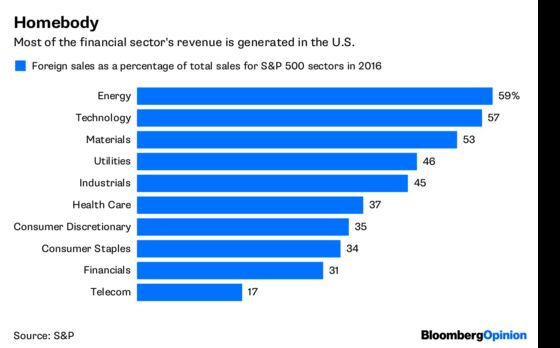

And the financial sector would be among the least affected by a trade war. Roughly 31 percent of the financial sector’s revenue was generated outside the U.S. in 2016, according to the latest numbers compiled by S&P, the second-lowest percentage among sectors. By comparison, 57 percent of the technology sector’s sales came from overseas, and investors don’t seem nearly as worried about tech firms.

The better explanation is that talk of stress test is colliding with investors’ actual stress about yield curves and trade wars and conjuring memories of the financial crisis.

But if the numbers don’t persuade investors that the next crisis won’t look like the last one, then maybe a look at previous bear markets would. In reverse chronological order: The bursting of the dot-com bubble was behind the downturn from 2000 to 2002. A mass panic or newly introduced computerized trading, depending on whom you ask, set off the 1987 crash. Stagflation brought down the market from 1980 to 1982. A global oil embargo hit stocks from 1973 to 1974. I could keep going, but you get the idea.

There is a common thread running through the scariest episodes: high stock prices. The average cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings, or CAPE, ratio for the S&P 500 has been 18 since 1928, according to numbers compiled by Yale professor Robert Shiller. The five worst bear markets during those nine decades, as measured by peak to trough declines, commenced in 1929, 1937, 1973, 2000 and 2007. The average CAPE ratio on the eve of those downturns was 29 and the median was 27.

The current CAPE ratio: 32. And it’s never just stocks. Other assets in the U.S. look frothy, too, such as private equity and real estate.

In theory, asset prices should never get so rich. The traditional portfolio playbook calls for occasional rebalancing, which means selling assets that have done well and buying those that haven’t. But investors seem to have abandoned it.

Investors should let all that sink in. They may have been powerless to prevent earlier downturns, but they could have limited the damage by refusing to chase assets to lofty levels. They should now think about how they might be contributing to the wreckage of the next crisis. Here’s a hint: It probably won’t involve the banks.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.