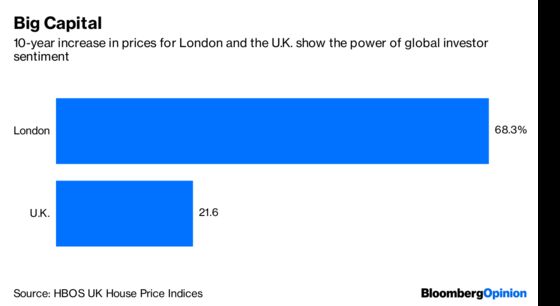

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Property bubbles have a habit of ignoring the fundamentals of having a roof over your head. The U.K.’s real-estate boom of the past decade was driven — especially in London — by government subsidies for buyers, cheap mortgages, and a fixation among investors that prices never go down. The less affordable homes became, the more they were sought after.

It took the U.K.’s Brexit vote and the subsequent rise in popularity of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party to prompt a re-think. Politicians of all stripes now agree the housing market is broken, and are unanimous on the fix: Boost supply to bring down prices.

Prime Minister Theresa May last year pledged 15 billion pounds ($20 billion) of support for new housing, and Labour promises to build 1 million affordable homes in 10 years if it gets into power. After years of “Help to Buy” packages, there’s a push for “Help to Build.”

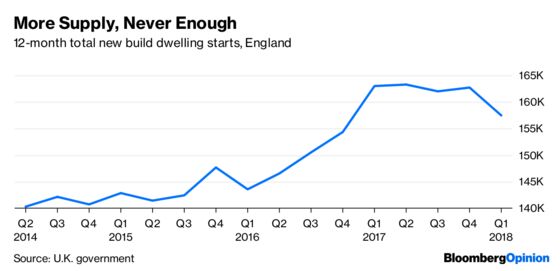

Britain has a pretty poor record when it comes to house-building. Government figures suggest an estimated 240,000 to 300,000 homes are needed a year in England, but actual supply hasn’t cracked the 200,000 mark in at least 10 years. Taking into account vacant and second homes, there’s a shortage of about 1.25 million homes in England, by one estimate. France, by contrast, pumps out around 350,000 new dwellings a year.

But replacing buy with build won’t suddenly iron out the inefficiencies, inequalities and misaligned incentives in this market.

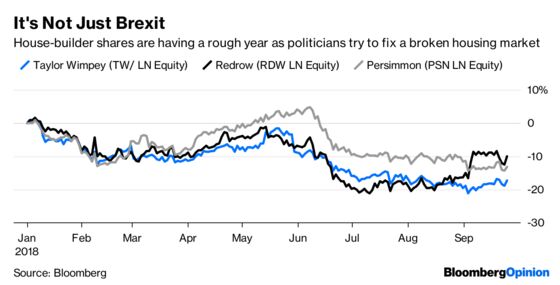

Who is doing the building? Britain is dependent on the private sector, and these companies have become rather adept at enriching their stakeholders first. Take leasehold agreements, common in the U.K., where the homebuyer owns their property for a limited time and according to rules set by a third party, the freeholder. Intended to make life simpler for owners of apartments in a single property, it has become a money-making wheeze: Some developers sold properties with terms so medieval that the annual charges, or ground rent, paid to the freeholder would double every decade.

It has taken public outrage, and a refusal by one mortgage lender to finance such properties, to get the government on the case. There will be a ban on leaseholds for almost all newly built homes, and developers have issued a mea culpa. Homebuilder Taylor Wimpey Plc alone has set aside 130 million pounds to compensate customers. But these reforms will take time, and it’s not clear what the exemptions will be. In the meantime, building more homes is still seen as the overarching solution.

Micro factors like red tape and regulation matter just as much as macro factors like supply and demand when trying to improve a market. U.K. house prices are now more than 150 percent higher in real terms than they were 20 years ago, according to Oxford Economics’ Ian Mulheirn. A big house-building boost might bring them down by an estimated 5 percent. That’s not much.

Judicious use of rent controls, or longer leases, as controversial as they may be, would at least have the benefit of bringing costs down for tenants sooner, and in a big way.

Brexit has already done more to hurt London’s property market than the tens of thousands of homes built every year in the capital. But homes are still unaffordable: It costs a record 14.5 times the average salary to buy a property. Given those price-pumping government subsidies and low interest rates are likely to be with us for a few years yet, it’s time for quicker, more clinical measures.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering finance and markets. He previously worked at Reuters and Forbes.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.