Fed Is Sick of Being Held Hostage by Trade Wars

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues sent a message with their final interest-rate decision of 2019: Don’t expect us to be subject to the whims of America’s ever-shifting trade policy in the year ahead.

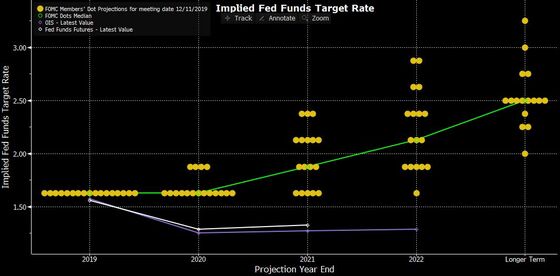

The Federal Open Market Committee, in its first unanimous decision since May, kept its benchmark lending rate unchanged in a range of 1.5% to 1.75%. The median projection in the central bank’s “dot plot” calls for no movement in the fed funds rate during the next 12 months, with 13 of 17 central bankers expecting to hold steady. All of this conforms with market expectations — after last week’s blockbuster jobs report, fed funds futures began to price out additional interest-rate cuts in 2020.

How the Fed opted to reword its statement heading into the New Year was perhaps the most striking takeaway from a decision that otherwise went as expected. Notably, it says “the committee judges that the current stance of monetary policy is appropriate to support” its goals and no longer contains the phrase “uncertainties about this outlook remain.” The central bank will continue to monitor “global developments” — its way of saying “trade wars” — but no longer views them as detrimental to the U.S. economy.

“This was a telling change given there is still no clarity on the trade front,” Ian Lyngen, head of U.S. rates strategy at BMO Capital Markets, wrote after the decision. “Perhaps Powell is also suffering from ‘trade drama fatigue?’”

It has been quite a year for Powell. At the beginning of 2019 he effectively told markets the Fed would be on hold just weeks after policy makers predicted two additional interest-rate increases in the coming 12 months. By June, bond traders were convinced the central bank would begin dropping interest rates in the following month. Now the fed funds rate is 75 basis points lower than in January. “That wasn’t in the plan in any kind of specific way in the beginning,” Powell noted in his press conference.

Powell may never say it, but the Fed was pushed around in a large way by the Trump administration’s trade policy. He said that “we try to look through the volatility in trade news” and that “monetary policy is not the right tool to react in the very short term to volatility and things that can change back and forth.” Either way, the central bank seems to believe it offset any threat that posed to the U.S. economy through its interest-rate cuts.

But heading into a U.S. presidential election year, the Fed truly wants to be on hold. And with this decision, it sought to make clear that it’s going to take more than just escalating trade rhetoric to get policy makers to change that view — in Powell’s words, only “if developments emerge that cause a material reassessment of our outlook, we would respond accordingly.”

Now, whether markets take this stance seriously is anyone’s guess. But it’s worth looking back at previous election years to see how resistant the Fed has been to abruptly changing course.

Many market observers seem to think the Fed doesn’t move interest rates one way or the other during an election year. That’s not entirely correct. Sure, the central bank did nothing in 2012, but in 2008 it dropped the fed funds rates by 225 basis points in the first half of the year and raised interest rates in both early 2000 and starting in mid-2004. As Carl Riccadonna of Bloomberg Economics put it: “A fundamental law of physics proves to be a useful rule of thumb for Fed policy in election years: Objects at rest will stay at rest and objects in motion will remain in motion.”

Here’s more from Riccadonna’s analysis:

“While the Fed is averse to any appearance of influence over political outcomes, it is not unprecedented to adjust policy in election years. What is unusual is a change of course or velocity of adjustments. … Policy makers attempt to maintain the status quo on policy through elections. If they were on hold in the preceding period, they remain on hold; if they are hiking gradually and predictably, they continue to do so, and so forth.”

Of course, the Fed has never faced the level of persistent attacks from a U.S. president as it has with Donald Trump. In some ways, it’s almost too late to avoid politicizing the central bank.

But there’s long been a theory in financial markets that Trump would keep escalating trade tensions with China, which would cause the Fed to further drop interest rates, and then the president would strike a deal at the last minute and cause a stock rally to buoy his re-election chances. Powell is acutely aware that markets are obsessed with these trade talks. “What’s been moving financial markets? It’s been news about the negotiations with China,” Powell said.

With this decision, Powell is telling Trump and traders that they can’t have it all in 2020. The economy is in a good place, thanks to the Fed’s decisive action to lower rates three times. If the president wants to keep the good times going in 2020, the ball is in his court. The central bank will be watching from the sidelines.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.