Fed Throws the Kitchen Sink at Short Rates and Still Struggles

Two months after the repo meltdown, the central bank is trying to reassert control by pulling all sorts of levers.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- “I think we have it under control.”

That’s what Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said when lawmakers in Washington asked him last week about the mid-September turmoil in short-term funding markets. New York Fed President John Williams said something similar on Tuesday.

If Powell didn’t sound entirely sure, it’s for good reason — the Federal Open Market Committee apparently isn’t, either. Minutes of the FOMC’s October meeting released on Wednesday showed that officials are puzzled about how to best regain their handle on short-term interest rates. According to the minutes, policy makers were presented with two possible options: either frequent repo operations like the past two months, or establishing a standing fixed-rate facility.

Fed officials hemmed and hawed:

“Many participants noted that, once an ample supply of reserves is firmly established, there might be little need for a standing repo facility or for frequent repo operations. Some of these participants indicated that a basic principle in implementing an ample-reserves framework is to maintain reserves on an ongoing basis at levels that would obviate the need for open market operations to address pressures in funding markets in all but exceptional circumstances. Many participants remarked, however, that even in an environment with ample reserves, a standing facility could serve as a useful backstop to support control of the federal funds rate in the event of outsized shocks to the system.

…

A couple of other participants suggested that an approach based on modestly sized, frequent repo operations that could be quickly and substantially ramped up in response to emerging market pressures would mitigate the moral hazard, disintermediation, and stigmatization risks associated with a standing repo facility.

…

Participants made no decisions at this meeting on the longer-run role of repo operations in the ample-reserves regime or on an approach for conducting repo operations over the longer run.”

That mostly sounds like they wish these pesky funding-market strains would just go away.

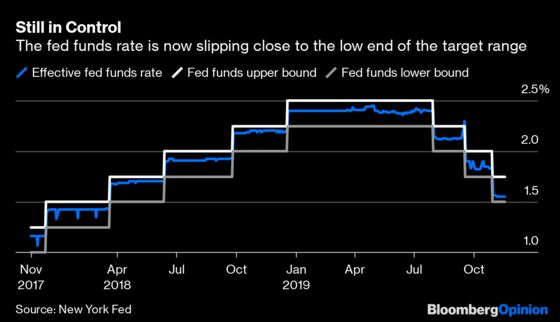

As Bloomberg News’s Alex Harris has reported, they haven’t. Rather, brokers have been quoting repurchase-agreement rates for the end of the year above 3% for months, a good deal higher than they should be based on the Fed’s benchmark lending rate. Meanwhile, the effective fed funds rate is under pressure in a different direction. It has been stuck at 1.55% for almost two weeks, which is unusually close to the lower end of the 1.5% to 1.75% target range.

The Fed often likes to reiterate that its dual mandate is to “support maximum employment and stable prices” by setting monetary policy. But the whole concept of “setting monetary policy” is often taken for granted. These recent months have shown that it’s not quite so simple.

Consider all the steps the Fed has taken since Sept. 16 just for Powell to get to the point where he thinks funding markets are under control:

- Sept. 17: The New York Fed conducts its first overnight system repurchase agreement in a decade, taking in $53.2 billion of securities.

- Sept. 25: The New York Fed increases the size of its overnight system repurchase agreement operations to a $100 billion maximum, from $75 billion previously, and also raises the limit on its 14-day term repo operation to $60 billion from $30 billion.

- Oct. 11: The Fed announces it will purchase $60 billion of Treasury bills a month and will keep doing so “at least into the second quarter of next year.”

- Oct. 23: The New York Fed boosts the size of its overnight repo offerings to at least $120 billion, a size it is set to maintain through at least Dec. 12.

- Nov. 14: The New York Fed says it will conduct two repo operations, each with terms of 42 days, on Nov. 25 and Dec. 2. With maximum sizes of at least $25 billion and $15 billion, these would carry past the end of the year.

Taken together, it’s readily apparent that Fed officials are throwing the kitchen sink at the short-term funding markets and hoping they’ll settle down. The results so far have been fine but hardly perfect. Powell told lawmakers that “we’re prepared to continue to learn and adjust, but it’s a process and it’s one that doesn’t have implications for the economy or general public.” That may be, but it certainly has ramifications for confidence in the central bank to carry out it’s core responsibility of controlling short-term interest rates.

As a reminder, the Fed’s problem not long ago was that the effective fed funds rate got too close to the top of its target range. That’s why policy makers inched the interest rate on excess reserves closer to the lower end of the band starting in mid-2018. Now that the fed funds rate is too close to the bottom — and right in line with the current IOER rate of 1.55% — some strategists say there’s a chance the Fed could increase IOER in December.

Even if it’s just 5 basis points, a small increase in interest rates after back-to-back-to-back cuts would undoubtedly raise some eyebrows on Wall Street. In addition to trying to convince investors that buying Treasury bills is not quantitative easing, Powell would also need to communicate that an IOER boost is not a rate increase.

Crucially, Powell’s claim that interventions in the funding markets don’t impact the general public is true only to an extent. The Fed’s various approaches have shaken up the $3.6 trillion money-market fund industry, a favorite of individual investors. Treasury bill auctions have become more competitive now that the Fed is also in the market. Short-term rates have tumbled. And now, as Harris reported this week, money-market investors appear to be starting to use the central bank’s reverse-repo facility as a workaround, parking the most cash there since the middle of the year.

In case you read over it: that’s the Fed’s reverse repo facility. In its repo operations that have made headlines, the central bank absorbs excess securities and floods the market with cash. That makes sense, given the recent liquidity crunch. But this is the opposite — taking cash out of the system, effectively countering the Fed’s moves to bolster reserves.

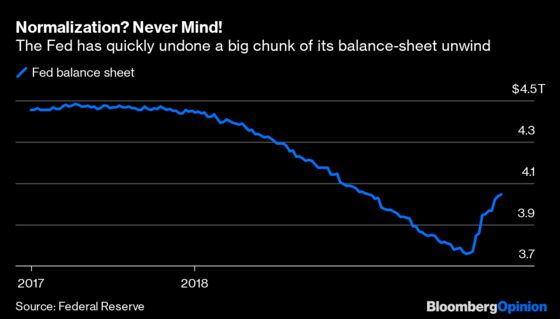

If there’s one top-line takeaway from all these machinations, though, it’s the sharp increase in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. It now stands at $4.05 trillion, up from $3.76 trillion in late August. Basically, in just more than two months, the central bank has reversed almost 40% of its normalization. Its assets are now back up to the same level as around the start of the year, soon after President Donald Trump told the central bank to “stop with the 50 B’s.” I panned that remark at the time, noting that if the Fed didn’t trim its holdings then, it was basically admitting it could never go back to a more historically normal level.

In hindsight, policy makers probably wish they had just kept reserves overly abundant. The alternative is what we’re seeing now — a hodgepodge of fixes that keep investors on edge and increase scrutiny of the Fed’s handle on its core rate-setting capabilities.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.