The Bond Market Is a Powder Keg. Can the Fed Defuse It?

Yields are throwing a tantrum across the globe, forcing central bankers to grapple with elevated inflation.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Taper Tantrum 2.0 has arrived just as the Federal Reserve plans to start scaling back its asset purchases. This time is different from the original edition in 2013 in a few important ways — raising the stakes for Chair Jerome Powell and the central bank, which will issue its latest decision at the conclusion of its meeting on Wednesday.

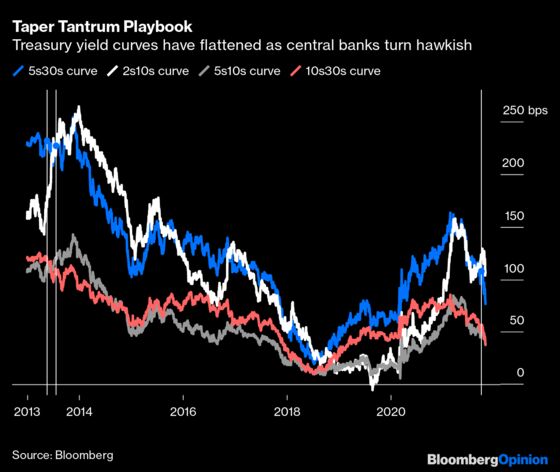

First, unlike eight years ago, traders in the $21.9 trillion U.S. Treasury market clearly understand the playbook: a combination of tapering and a potentially accelerated pace of interest-rate increases means a sharply flatter yield curve. From May 22 through July 3 in 2013, the curve from five to 30 years flattened by about 25 basis points. Last month, in a shorter time frame, the same curve flattened by roughly 40 basis points. Other curves steepened during the previous episode. Regardless of maturity, the flattening trend has been unmistakable this time around.

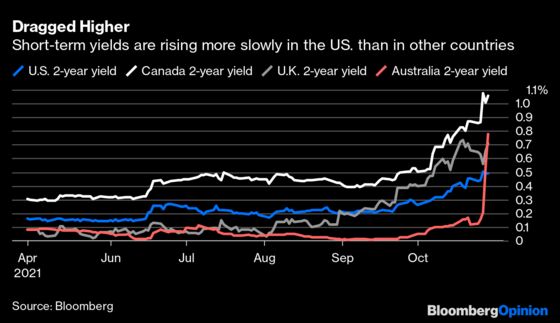

Crucially, this latest bout of bond-market upheaval is a distinctly global phenomenon. That’s a problem for the Fed. Even if it’s the world’s most influential central bank, there’s only so much it can do to dictate policy decisions in other large developed nations, which have their own domestic considerations. Here’s a snapshot of what has happened lately across sovereign debt:

- Canada: Two-year yields more than doubled in October to 1.04%, including a spike of more than 20 basis points in one day as the Bank of Canada ended its bond-buying program and moved forward the potential timing of future rate increases.

- U.K.: Two-year yields have been rising for 10 consecutive weeks, the longest stretch in at least three decades. Markets expect that the Bank of England will increase its benchmark rate to 0.25% from 0.1% the day after the Fed’s decision.

- Australia: Two-year yields increased more than 50 basis points in two days, ending Friday at 0.775% from just 0.115% a week earlier. The Reserve Bank of Australia opted not to defend its short-term target level through yield-curve control.

- New Zealand, Norway, South Korea: The central banks in these countries have already raised interest rates.

- Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece: Shorter-term rates as well as 10-year yields are surging in these so-called peripheral countries within the euro zone. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde’s remarks last Thursday were taken to be not-so-dovish, and by Friday, “that caution mushroomed overnight into a mini taper tantrum,” FHN Financial’s Jim Vogel wrote.

Taken in its entirety, the global bond market looks like a powder keg, even if stocks and credit are largely shaking it off for now. That raises the all-important question: Does the Fed have the tools to prevent a blowup?

Wall Street strategists aren’t necessarily convinced. Citigroup Inc.’s Matt King sees the Fed and its peers caught between a rock and a hard place. “Expect tantrums in risk if central banks respond to inflation — and tantrums in bonds if they don’t,” he wrote in an Oct. 29 report. At Jefferies, Aneta Markowska and Thomas Simons pondered whether Powell will look to dial back the market’s current bets on two interest-rate increases next year. He “will have to walk a very fine line, since pushing back too hard could unhinge inflation expectations, but not pushing back at all could unsettle the front end of the curve,” they wrote.

Here’s what we know for certain: The Fed doesn’t like to surprise markets. Just about everyone expects the central bank to say it will start scaling back its $120 billion of monthly bond purchases ($80 billion in Treasuries, $40 billion in mortgage-backed securities) by $15 billion a month ($10 billion in Treasuries, $5 billion in MBS) starting in mid-November and ending by June. That’s what should happen come Wednesday. It gives Powell and his colleagues eight months to ever-so-slightly pare back accommodative policy and hope in the meantime that inflation comes down and validates their long-held position that price pressures are transitory.

Ideally, the Fed would have a better strategy than hope. But it has boxed itself into a difficult situation with its new policy framework, which was designed with the post-2008 economy in mind. That period was characterized by a gradually improving labor market without much wage pressure or inflation broadly. It suggested that reaching the nebulous level of “full employment” doesn’t mean price growth will reach or exceed the central bank’s 2% target.

The framework wasn’t meant to address the current situation: persistently elevated inflation when the number of working Americans is still well below its February 2020 levels. Yes, it’s good to see that the employment cost index, a broad gauge of wages and benefits, rose 1.3% in the three months through September from the prior quarter, the biggest jump on record. But if consumer prices are rising more quickly — and especially if individuals and companies expect they’ll only go up faster in the future — then the Fed is violating the price-stability part of its mandate by staying the course, to say nothing of its supposed data dependency.

The best way for Powell to defuse the situation is by first acknowledging that the pace of tapering isn’t on autopilot and that the central bank reserves the right to speed it up or slow it down based on incoming data. It would take a severe shock for that to happen, of course, but just hinting at that optionality would show that it hasn’t abandoned its commitment to keep inflation well-anchored. Second, he would be wise to steer clear of directly trying to influence the market pricing of short-term rates, only saying that officials were split about increasing the fed funds rate in 2022 as of September, and that they will update their forecasts next month based on the latest information. As it stands, I’d expect December’s dot plot to reflect a median expectation of one rate increase within a year, meeting current market pricing halfway.

Suffice it to say, it’s a delicate balancing act. It’s made a bit easier by the fact that the bond market’s tantrum hasn’t yet spilled over into credit spreads or equity prices, and made more difficult because Powell isn’t even sure he’ll be Fed chair in a few months. Will there be a hard policy pivot, or is this just bond traders getting ahead of themselves about inherently uncertain actions months down the line?

It’s up to Powell to navigate this treacherous path. Announcing the start of tapering will be the easy part.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.