The Fed and Markets Enter Into an Uneasy Peace

Traders are cautiously prepared to believe Jerome Powell and give the U.S. economy the benefit of the doubt.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- We have an uneasy peace on our hands. A year ago, world markets began to fight the Federal Reserve. Only now does it appear that they have reached a truculent truce, with honors roughly even: Stocks are at an all-time high, while the U.S. economy — having lost some steam — may still manage to avoid a recession.

How did we get here? To rewind: By late 2018, Jerome Powell, recently installed as Fed chairman, had made clear that he wanted to continue shrinking the huge balance sheet of assets the Fed had acquired to fight the crisis, with a steady unwind that was meant to progress “on autopilot.” He also intended to keep raising the bank’s target rate, as he sought to normalize monetary policy and guard against the risk of asset-price bubbles. Traders had none of it, and their rebellion prompted a series of tantrums in both the stock and bond markets. By the close on Christmas Eve, the S&P 500 Index had fallen slightly more than 20% from its recent peak, taken by many as the definition of a bear market.

In the bond market, meanwhile, 10-year Treasury yields — which had climbed toward 3.25% last November in anticipation of higher rates — reversed course and plummeted. The thinking was that unwisely tight policy from the Fed, in combination with the trade war and signs of economic trouble for China and Germany, would drive a global recession. By August, the 10-year Treasury yield had dropped to 1.43%, while the equivalent German bund yield had fallen to the incredible level of -0.73%. Inflation expectations tumbled. And most alarmingly, the yield curve inverted, meaning that short-term bonds yielded more than long-term bonds, in a reversal of the normal pattern. Over time, an inverted yield curve has proved to be the most reliable signal of an approaching recession. Taken together, these moves only made sense if the world was braced for an imminent downturn.

Somehow, we have since scrambled back from the brink. Powell has canceled plans to keep reducing the balance sheet, and has been forced to start buying short-term bonds to ease problems in the money market. The Fed complains, with some reason, that this isn’t technically “QE” — the crisis-era purchasing of long-term bonds in an attempt to stimulate the economy — but for many this is just a technicality. The central bank’s balance sheet is expanding once more.

The Fed also cut its target rate three meetings in a row, bringing the upper bound down from 2.5% and 1.75%. It did this almost literally kicking and screaming, with Powell attempting to draw a line following each rate reduction. At the start in July, he tried to dismiss that cut — the first in more than a decade — as nothing more than a “mid-cycle adjustment.” The market didn’t believe him, and relentlessly placed new bets that he would be forced to cut more.

But other events conspired to help Powell. Both sides in the U.S- China dispute now appear at least to be trying to stop an escalation, even if uncertainty and distrust persist. Chinese economic data remain weak by Chinese standards, with growth down to “only” 6%, but aren’t in free fall. And in the U.S., the labor market remains obstinately robust, the housing market is strengthening and consumers are still buying. There are plenty of reasons for concern, but it is hard to make a case for an imminent recession.

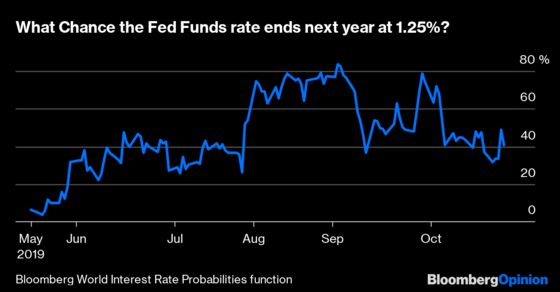

After this week’s Fed policy meeting, which was accompanied by a welter of data from around the world, there is now a cautious preparedness to believe Powell. According to Bloomberg calculations, fed funds futures are signaling expectations for one more cut by the end of next year, putting the chances of this happening at about 80%. Meanwhile, the odds of the central bank going any further, and dropping the fed funds target to 1.25% or lower, are perceived to have been sharply reduced:

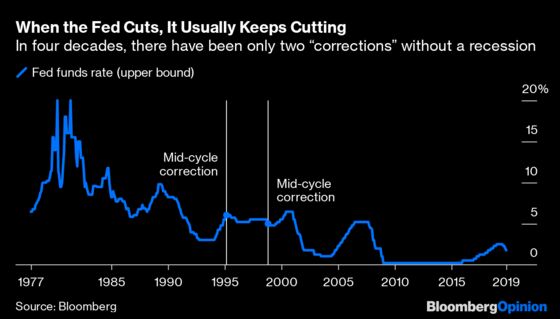

There is significance to this. Generally, when the Fed starts cutting rates, it keeps doing so for a while. Like the economy it is attempting to regulate, the central bank’s monetary policy tends to move in long cycles. “Mid-cycle adjustments,” where the Fed cuts rates briefly and then desists, are rare. Indeed, since Paul Volcker took over the in 1970s and tamed inflation, there have only been two such mid-cycle corrections, in 1995 and 1998. Both of them stopped after three cuts for a total of 75 basis points.

Every other cycle of cuts has been followed by a recession, and has involved slashing rates by at least 5 percentage points. That isn’t going to happen this time, as the fed funds rate topped out at 2.5%. But if the consensus is that the Fed is likely to cut only once more by the end of next year, it follows that the consensus also is that there won’t be a recession by then either. Alan Greenspan stopped at 1% after the dot-com bubble burst, while Ben Bernanke cut down to 0.25%, so if investors still held a serious belief in a coming recession, there would be far more intense pressure to cut rates further.

The lifting alarm is also visible in bond yields, which have stabilized and started to rise a little, while U.S. stocks, as mentioned, have moved to set new all-time highs. Sentiment is nervous and guarded, but for now the market is prepared to give the Fed, and the U.S. economy, the benefit of the doubt.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.