Fed Aims to Radically Transform Funding Markets

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- At the highest level, it looks as if the Federal Reserve hasn’t done much of anything for several months. Interest rates remained pinned near zero. Officials insist that any moves higher in inflation are transitory. Asset purchases continue unabated.

However, a significant shift appears to be brewing beneath the surface at the central bank that could drastically reshape a part of critical market plumbing, potentially preventing bouts of illiquidity in the $21.5 trillion Treasury market and altering balance-sheet calculations at the largest U.S. banks.

Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee’s April meeting, released last week, indicated that a “substantial majority” of officials see the benefits outweighing the costs of installing what’s known as a “standing repo facility,” which would effectively make permanent the emergency measures that the central bank rolled out during periods of turmoil in the funding markets in September 2019 and the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020. It’s rare to see such a statement of widespread agreement.

The benefits of the Fed flooding the financial system with cash during moments of stress are fairly straightforward. The option for banks or foreign investors to place U.S. Treasuries with the Fed as collateral and receive funds is far less disruptive than selling them into a market that has few buyers. The promise of such a backstop would make government bonds a true cash equivalent for large banks that are subject to liquidity constraints. Recall that in early March 2020, 30-year Treasury yields fell 85 basis points and then surged 63 basis points in the span of days — the world’s biggest bond market isn’t supposed to trade like that. Investors had to offload their holdings, and dealers weren’t in a strong position to step in and fill the void. The resulting chaos froze many other markets until the Fed stepped in to buy almost everything.

A St. Louis Fed report from March 2019, before the two high-profile blowups in funding markets, made the case for a standing repo facility. The hypothetical structure features an interest rate that would be higher than the fed funds rate, but only modestly so, such that institutions would flock to the central bank any time repo rates increased too much:

This administered rate could be set a bit above market rates — perhaps several basis points above the top of the federal funds target range — so that the facility is not used every day, but only periodically when a bank needs liquidity or when market repo rates are elevated.

With this facility in place, banks should feel comfortable holding Treasuries to help accommodate stress scenarios instead of reserves. The demand for reserves would decline substantially as a result. Ample reserves — and therefore the size of the Fed’s balance sheet — could in fact be much closer to their historical levels.

In theory, a standing repo facility would increase demand for Treasuries from large banks subject to stress tests and other regulations because the Fed would pledge to take them in exchange for cash. In early 2019, the New York Fed found that the following eight banks alone would potentially want to hold $784 billion in precautionary reserves: Bank of America Corp., Bank of New York Mellon Corp., Citigroup Inc., Goldman Sachs Group Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co., Morgan Stanley, State Street Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co. That wouldn’t be necessary “if higher-yielding Treasuries could be liquidated at a modest discount on a reliable basis in times of stress,” noted David Andolfatto and Jane Ihrig, the authors of the St. Louis Fed report. The trade-off between reserves and Treasuries has only drawn more attention since then because of the frenzy earlier this year over the supplementary leverage ratio.

So what exactly are the costs of a standing repo facility? The FOMC minutes mention a few, which don’t hold up to much scrutiny and can seemingly be avoided with the right parameters:

A standing repo facility could be seen as a form of liquidity support for nonbank financial institutions, and one that could create incentives for firms with access to the facility to take on more liquidity risk against eligible securities than would otherwise be the case.

...

A few participants mentioned that a standing repo facility could be perceived as a means of supporting the financing of the U.S. Treasury or as a permanent Federal Reserve liquidity backstop for nondepository institutions; a couple of others called out the risk that such a facility could crowd out private market sources of liquidity provision.

The proposal from Andolfatto and Ihrig assumes primary dealers are the Fed’s only counterparties, as they are today. In practice, those banks pass that liquidity over to hedge funds, which use borrowed cash to leverage up positions in strategies such as the cash-futures basis trade. It stands to reason that the Fed’s standing facility would help those investors secure cheaper and more stable funding. I’ve asked before why the U.S. central bank should be in the business of ensuring smooth sailing for this type of leveraged arbitrage strategy. It’s fair that some FOMC participants are raising that concern as well.

Unsurprisingly, it seems as if some officials are trying to figure out how to frame the facility in the context of the Fed’s core monetary policy objectives. For instance: “Several participants noted the facility’s design should be targeted specifically to enhance control of the federal funds rate rather than to limit volatility in the repo market.” I don’t see how the latter can be avoided when the objective is to offer a place for banks to liquidate their Treasuries at a moderate discount. That by definition dampens repo volatility.

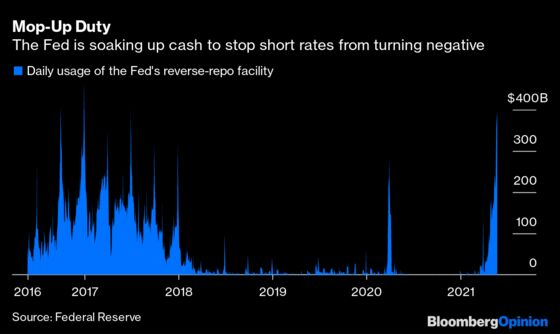

Just look at what’s happening now on the flip side of the repo market. The Fed’s overnight reverse repurchase facility had 54 participants place $395 billion of cash with the central bank in exchange for a 0% interest rate on Monday, the highest since June 2017. If the Fed weren’t mopping up huge amounts of excess liquidity, it stands to reason that its zero-rate floor would have already cracked by now and more T-bills might offer negative rates, which would likely spark volatility. A standing repo facility with a rate near the upper bound of the target fed funds range would function as a similar release valve.

As for the concern that a standing repo facility “could be perceived as a means of supporting the financing of the U.S. Treasury,” that ship has long since sailed. After yields whipsawed in March 2020, the Fed announced a series of actions that included hundreds of billions of dollars of repo operations a day, saying at the time that “these changes are being made to address highly unusual disruptions in Treasury financing markets.” The Fed still justifies its $120 billion of monthly asset purchases as a way to “foster smooth market functioning.” Like it or not, the central bank will always have a large footprint in the Treasury market.

U.S. Treasuries and short-term funding markets have had large enough volatility spikes over the past two years to think there has to be a better way. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies might swing wildly, but why should supposed risk-free assets? There was no fundamental reason 10-year Treasury notes traded at a 0.92% yield on March 6, 2020, fell to 0.31% after the weekend and then jumped to 1.02% by the end of the week. It was simply a case of broken price discovery that the Fed could have handled. Instead, the delay caused some painful weeks.

Many investors bristle at any perceived overreach by the Fed. Certainly, buying U.S. corporate debt was an extreme measure, and the central bank should probably stop purchasing mortgage-backed securities at this point. But repo, Treasuries and the banking system are well within its domain. Done right, the central bank has the chance to address the market plumbing that has flared up one too many times lately.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.