We Wish to Be Entertained, in Person

More and more jobs are being created in arts, entertainment and recreation. The pay isn’t great, though.

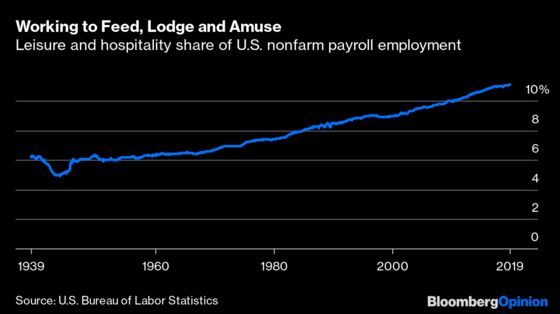

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- From the 1930s through the 1960s, employment in leisure and hospitality held relatively steady — apart from an understandable drop during World War II — at a little over 6% of U.S. nonfarm jobs. Then it began its great rise. As of last month, its share was 11.1%.

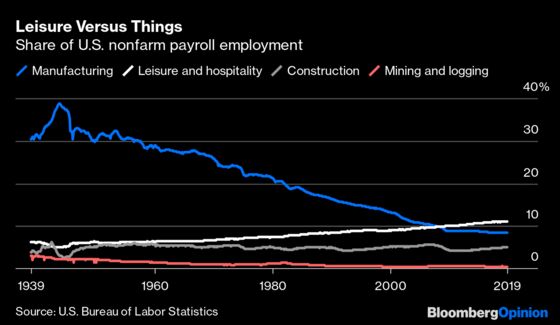

In the 1950s, about five times as many Americans worked in manufacturing as in leisure and hospitality. During the last recession, employment in leisure and hospitality passed employment in manufacturing for the first time. Now it’s 31% higher.

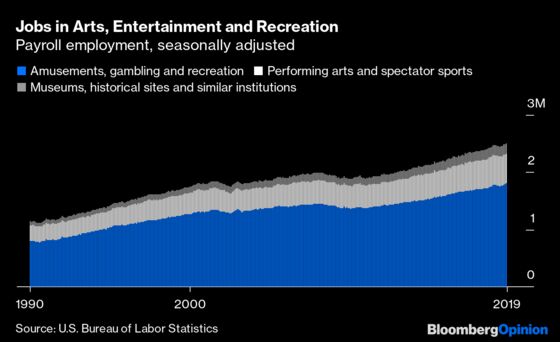

Almost 73% of these leisure and hospitality jobs are now in food services, and I and others have written before about the spectacular restaurant hiring boom of the past decade. An additional 12% are in accommodation, but its share of nonfarm employment hasn’t budged since the mid-1980s. That leaves the “leisure” part of leisure and hospitality, which employs far fewer people than restaurants do, but has seen even faster job growth since 1990.

These more detailed data series are available back only to 1990; I started out with the overall leisure and hospitality numbers, which go back to 1939, mainly to get a longer-run perspective. Also, the forces driving employment gains on the hospitality and on the leisure sides are not unrelated. Both cater to consumers with extra money to spend and a desire to get out of the house (and in some cases be entertained), and both are quite labor-intensive. If they get more customers, they generally need to hire more workers.

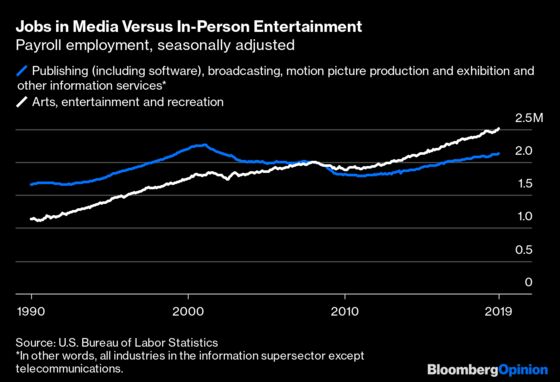

This is less true of the industries that deliver amusement and information remotely — aka the media, broadly defined. Which is one reason employment in arts, entertainment and recreation passed media employment during the last recession (and yes, that media total includes the likes of Facebook and Google).

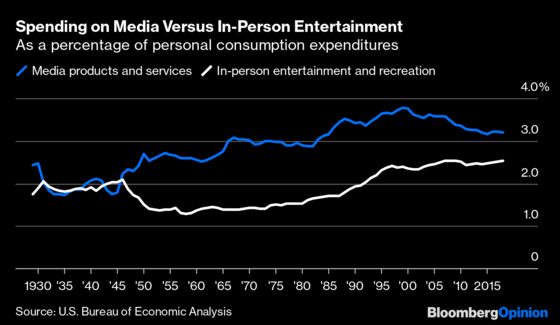

Americans still appear to be spending more on media than on its in-person competitors, although the gap seems to have narrowed over the past two decades. I use the tentative language because the Bureau of Economic Analysis spending categories in the chart below don’t match up perfectly with the Bureau of Labor Statistics employment-by-industry categories in the chart above. But they should at least be in the ballpark, and they tell an interesting story going back all the way to 1929.

The 1950s through 1990s were a golden age for U.S. media industries. Television wrested hours of leisure time away from other activities and high-fidelity stereos brought a music-listening and -buying boom, while book, magazine and newspaper publishers were able to wrest enough money out of consumers and advertisers to thrive even in a somewhat diminished role.

By the late 1990s, though, the impact of new communications technologies was becoming apparent. For regional newspapers, they destroyed existing business models and left consumers with reduced product offerings. For musicians, they shifted value away from recordings and toward live performances. But for the media overall, the internet and other technological advances have mainly brought higher productivity. In publishing, which includes software and video games, real output per hour worked (aka labor productivity) is up 211% since 1990. In broadcasting, it’s up 156%. Fewer people are delivering more media content at relatively lower prices. That’s economic progress — although of course it hasn’t always felt that way to those of us who work in the media.

The situation is different for most forms of in-person entertainment and recreation, and has been for quite a while. As economists William Baumol and William Bowen wrote in 1966, “the arts cannot hope to match the remarkable record of productivity growth achieved by the economy as a whole.” Orchestra concerts, plays, museum exhibitions, non-slot-machine gambling and many other in-person entertainments and amusements are delivered in pretty much the same form they were centuries ago. Among the handful of arts, entertainment and recreation industries for which the Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks output per hour, gambling industries, fitness and recreational sports centers and bowling centers have seen some labor productivity gains in recent years, but amusement and theme parks and golf courses and country clubs have seen declines. At restaurants and other eating places, which face similar issues, productivity is up just 8.7% since 1990.

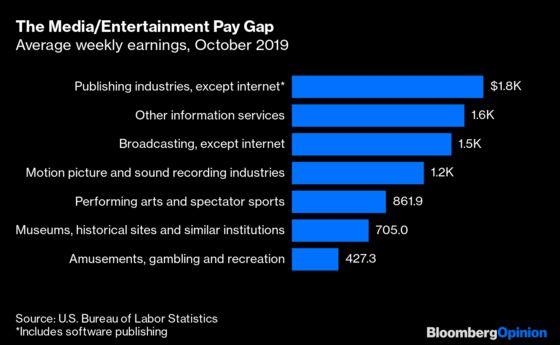

When Baumol and Bowen studied this phenomenon they were mainly interested in how low productivity growth drives up costs in the performing arts, and “Baumol’s cost disease” or the “Baumol effect” has since become a much-discussed phenomenon in relation not just to the arts but also to higher education, health care and other service sectors, with services generally experiencing slower productivity growth than the economy as a whole. A related effect that is quite apparent in arts, entertainment and recreation is that low productivity and slow productivity growth translate to low wages — which I’ve contrasted here with the substantially higher wages in some media industries.

Slow productivity growth also translates to slow economic growth. In his new book “Fully Grown: Why a Stagnant Economy Is a Sign of Success,” University of Houston economist Dietrich Vollrath estimates that the shift in economic activity from goods to services is responsible for 0.2 percentage points of the 1.25 percentage-point slowdown in per-capita U.S. economic growth since 2000. (He apportions the majority of the decline, 0.8 percentage points, to demographics, namely falling birth rates and the aging of the population, and the rest to slowing turnover of jobs and companies and to declining geographic mobility.)

As Vollrath’s book subtitle indicates, he doesn’t see this shift to services as necessarily a bad thing. Rising productivity in goods production has meant we have more money left over to spend on services. A lot of that money has gone to health care, which is a mixed blessing, but really who can complain about higher spending on arts, entertainment and recreation? It just doesn’t happen to be a ticket to prosperity for most of the people providing it.

Employment in accommodation has probably been undercounted in recent years, as those who rent out houses and apartments via Airbnb generally don't show up in the data.

The categories I added together to get the media spending number were recreational books; magazines, newspapers and stationery; andaudio-video, photographic, and information processing equipment services. I left out the video, audio, photographic and information processing equipment and media category because, while it includes once-popular media products such as CDs and DVDs, it also includes a lot of electronics equipment.For in-person entertainment the two categories were (1) gambling and (2) membership clubs, sports centers, parks, theatersand museums.

Motion picture and sound recording industries includes both the production side and those who work at movie theaters, which is why its average weekly earnings are lower than those of the other media industries.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at sshick@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.