(Bloomberg Opinion) -- April is the cruelest month. It’s not just English literature professors who’ll tell you that: Their university’s treasurers probably think T.S. Eliot had a point too.

Nowadays most of the English universities’ income arrives via student fees, instead of direct government grants. Half the money is released to them by the U.K.’s Student Loans Company each May, whereas costs for stuff like paying lecturers and keeping the lights on are spread out over the year; so things are often pretty tight by April.

This all creates an inherent imbalance in how cash flows in and out of the institutions, which isn’t helping to ease the pressure on the finances of England’s universities (with Brexit partly to blame). One unnamed establishment has already had to go cap in hand to the regulator, the Office for Students, for a temporary loan. If the universities’ latest published accounts are any guide, it won’t be the last. While large institutions have gone on a 12 billion-pound ($15.4 billion) borrowing binge, it’s the smaller, less well-funded ones we really need to worry about.

In an apparent effort to lift standards by fostering competition, English universities are free nowadays to recruit as many students as they can. As I’ve explained before, this process of turning higher education into a market-based business has created unhappy consequences, including massive pay-hikes for university bosses, easier admission requirements and rampant grade inflation. With each student representing about 28,000 pounds of potential income over a three-year course, there’s been an almighty battle to boost their numbers.

Hence universities are spending hundreds of millions of pounds on shiny new equipment, lecture halls and sports complexes, which the largest have financed in part by issuing long-duration public bonds at extraordinarily low yields. (Others have turned to private placements).

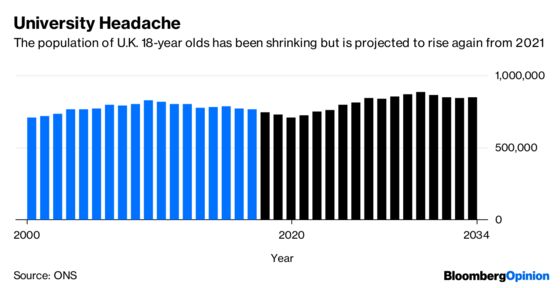

The trouble is, there aren’t enough students to go around right now. A British demographic dip doesn’t bode well for the overall undergraduate intake between now and 2021. Lower recruitment is doubly painful because it reduces rental income from student lodgings too. Meanwhile, Brexit will probably dry up EU research funding and put off European students. Wage inflation and giant pension deficits are another drag.

This perfect storm could get worse. The government has already put a stop to fees rising in line with inflation, and a review of university funding might result in the 9,250-pound maximum fee being slashed. Students would love that, but it’s not clear how universities would fill the funding gap. Unlike in the U.S., most British institutions don’t have big endowments – with two-thirds of the assets held by just eight institutions. Oxford and Cambridge are in no danger of going bust.

Less prestigious establishments will just have to keep generating cash surpluses to build up their financial reserves. For several years, most were able to do so, helped by those higher fees and rising student numbers. Now their cash flow forecasts could be exposed as optimistic and their liquidity buffers too small.

So far, the regulator has given all registered institutions a clean bill of health, which means it sees no material risk that they won’t be able to pay their debts in the next three years. But we can hardly relax. The Office for Students would be extremely wary about questioning a university’s finances in public, as it would risk becoming a self-fulfilling prophesy similar to a bank run – students won’t apply to a body they fear might collapse.

Universities’ financial accounts also probably flatter their available resources. Their fiscal year ended in July, meaning that the big chunk of student fees that arrived in May hadn’t all been spent yet. Even so, it’s not difficult to find examples of strain. A quick perusal of the published accounts turned up three institutions – the University of Chichester, Buckinghamshire New University and the University of Sunderland – that have breached banking covenants in recent years.

Chichester told me its 2018 covenant breach was a “minor accounting technicality” related to an accommodation finance lease, for which it received a waiver from the bank. But that’s not the whole story. Having spent about 31 million pounds on a technology park, which was opened by the Duke and Duchess of Sussex in October, the university encountered “significant budgetary challenges” linked to lower-than-expected student intake, according to its latest accounts. It’s been forced to slash costs (about 9 percent of the workforce took voluntary severance) and consider asset sales. With less than 5 million pounds of cash at the bank at the financial year-end, the university secured a new loan facility with HSBC Holdings PLC in November. Chichester said its restructuring had resulted in a “resilient and financially-secure organisation.”

The University of Sunderland breached a banking covenant in 2015/2016. It too received a waiver from the bank and worked with it “to put in place a sustainable financial plan”, according to a spokesperson. Yet the latest accounts still show negative net current assets, meaning its financial obligations over the next 12 months exceed its immediate resources. The spokesperson said that “in common with the sector, cash reserves at Sunderland are under pressure at various points during the year” because of the timing of the Student Loans Company payments. But they said the university had a short-term overdraft in place to help it cope and that the financial position had improved and would revert to a “net current assets position within the next few years.”

Buckinghamshire’s accounts showed the “short-term cash flow issues” that led to a “technical breach” during the 2017 financial year had been resolved and it also received a waiver from the bank – although a covenant on cash balances has been toughened. The university told me its recent student intake was “strong” and that it was on track to return to an operating surplus. Still, all three cases show that this is a difficult time to be a treasurer.

Some universities are opening glittering overseas campuses to compensate for the domestic pressures, but that isn’t without risk either. The University of Reading’s Malaysian offshoot has run up losses, for example, forcing the parent to book 21 million pounds of provisions in its latest accounts. Reading’s yearly loss was of a similar size.

Still, there are ways of heading off financial difficulties. Most universities have land they could sell or halls of residence they can sell and lease back. Cutting unprofitable courses and jobs is another option. Reading, Bradford and Plymouth have all announced redundancies. Failing that, they might want to try that corporate favorite: The merger.

Another risky option is to keep on borrowing to tide themselves over until the 2020s, when the cohort of 18-year-olds entering tertiary education is expected to rise again. Indeed, for cash-strapped universities the three most beautiful words in the English language right now are: Revolving Credit Facility. “The banks are really worried about their loans to universities, but they haven't got a choice,” says Matt Robb, an education consultant at EY-Parthenon. “Nobody wants to be the first bank to push a university over the cliff.”

Some will view these strains as proof that the free market in higher education hasn’t gone far enough. Maybe we should just let weak universities fail and the best get bigger. Indeed, the Office for Students’ policy is to not rescue failing institutions but, frankly, I don’t believe it. After spending tens of billions bailing out irresponsible banks, it’s inconceivable that the government would deny a comparatively affordable bailout to a university. They’re often big employers in socially-deprived areas.

When issuing 300 million pounds of bonds in 2017, the University of Southampton warned investors that “if higher education providers are allowed to fail” there could be “a reputational impact on U.K. universities as a whole,” which could affect student intake country-wide. No wonder credit rating agency Moody’s gives universities a one or two-notch uplift based on its “assumption of extraordinary support.”

While this is all very reassuring for students, it does create banker-style moral hazard for those overseeing an institution’s finances. The vast pay-packets of some vice-chancellors show this taking root. It’s a reminder, too, that higher education isn’t close to being a functioning market. It really shouldn’t have been compelled to become one in the first place.

The rest is paid during the first and second academic terms, in 25 percent installments.

This more comprehensive study found five institutions that had cash and other liquid resources that would only cover 20 days of expenses, or less. That's not much of a cushion.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.