Devin Nunes Isn’t the Only Dairy Farmer Souring On California

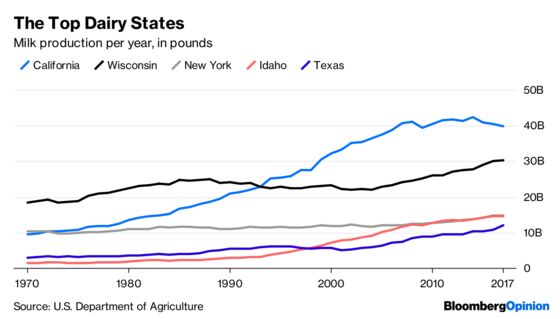

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For the past few decades, the heart of America’s dairy industry has been in the dusty flatlands of California’s San Joaquin Valley. Milk and milk products are California’s most valuable agricultural commodity, ahead of the grapes, almonds and lettuce for which the state is better known. California passed Wisconsin in 1993 to become the No. 1 milk-producing state, and Tulare County, between Fresno and Bakersfield, passed Southern California’s San Bernardino County to become the nation’s No. 1 dairy county a couple of years before that.

You may notice a dip in California milk production since 2014, though. It’s not a fluke! Earlier this week came the news, for example, that the family of Tulare County’s most famous dairy farmer, U.S. Representative Devin Nunes, had quietly moved its operations to northwestern Iowa a decade ago. Ryan Lizza has the details in Esquire, and I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether the story is of political significance or not. But while traveling through Iowa and South Dakota last month, I heard enough about the recruiting and arrival of California dairy farmers beset by drought and other hassles to know that it is of agricultural and economic significance.

It is also of technological significance, given that new and improved ways of ventilating dairy barns have been among the biggest drivers of the move. The first I heard of the trend, in fact, was when I stopped by the West Des Moines headquarters of the Iowa Farm Bureau, and David Miller, the organization’s director of research and commodity services — and a corn and soybean farmer on the side — told me that one of the two technological shifts that had done the most to change his state’s agricultural landscape over the past few decades was “the development of ventilation systems.” (I’m planning to give the other technological shift, involving farm-machinery hydraulics, its own column.) Breakthroughs in ventilation have already transformed how pork farming works in Iowa, the No. 1 pork-producing state, shifting it from something done on a small scale by lots of farmers to an activity conducted chiefly by big producers in gigantic barns with fans at one end. Now, he said, something similar was beginning to happen in dairy — and it was helping lure California dairies to Iowa and neighboring states.

California dairy farmers have never had to worry much about ventilation; they can just leave the cows outside all year. In two of the original centers of the state dairy industry, Marin County just north of San Francisco and Bellflower and Artesia just south of Los Angeles, it hardly ever gets very hot or cold (or at least didn’t until recently). Cows produce less milk when they’re steaming or freezing, so this was a big productivity advantage. As coastal development pushed California’s dairies inland, they did have to contend with hotter temperatures in the summer, but the humidity is so low that providing the cows with shade was generally enough to keep them happy — and California dairy herds long produced more milk per cow than those of any other state. It also helped that California farmers produced huge amounts of one of the cows’ favorite foods, alfalfa, because it keeps growing year-round there.

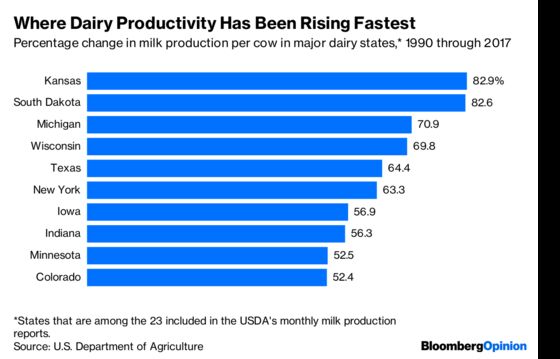

Then … things changed. Repeated droughts and pressure from environmentalists and urban water users led to supply restrictions and higher water costs for California farmers, many of whom replaced their water-hungry alfalfa fields with crops that used less water, brought in more money or both. The number of acres of alfalfa harvested in the state dropped from 1.1 million in 2006 to 700,000 in 2017. Meanwhile, new kinds of ventilated dairy barns made it possible to keep huge herds and achieve California-topping productivity levels in places with more extreme weather like Michigan — currently No. 1 in the milk-production-per-cow ranking, up from 11th place in 1990 — Colorado, Wisconsin, Kansas and Iowa (South Dakota came in just behind California in productivity in 2017 but has been gaining fast).

There are differing varieties of new-style dairy mega-barns, but the state of the art appears to be something called the low-profile cross-ventilated barn. The first one went into operation in Veblen, South Dakota, in 2005, and in 2008 a couple of Kansas State University professors organized a conference on “Dairy Housing of the Future” at the Holiday Inn City Centre in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, that will surely go down as a turning point in American dairy history. Actually, maybe it won’t, but the proceedings do explain a lot about how LPCV structures work (it involves gently sloping roofs, giant fans, baffles and insulation), and it does seem telling that Kansas and South Dakota have led the way in dairy productivity gains. Nebraska didn’t make the above chart because it isn’t considered a major dairy state (yet — Kansas and South Dakota weren’t either until a few years ago), but its per-cow milk production is up 73.6 percent since 1990. California’s, in case you were wondering, is up just 23.3 percent.

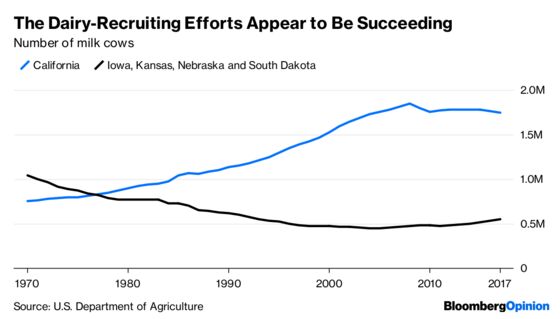

In 2015, CNBC’s Jeff Daniels visited Tulare’s annual World Ag Expo and reported that Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota had rented booths to recruit drought-plagued California milk producers eastward (so had Nevada and Texas). While North Dakota doesn’t seem to have had much success — it had only 16,000 dairy cows in 2017, the same as in 2015 and down from 32,000 in 2006 — it looks like the other states in the neighborhood have.

Among Midwestern states, Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin have also seen gains in the number of milk cows over the past decade, although I get the sense this has had more to do with investment by local dairies (and immigration from the Netherlands!) than recruitment of California dairy farmers.

The fact that some states are succeeding in wresting dairies away from California seems on the whole like a salutary development. California has so many people that it will still need dairies close by, but it has long seemed strange to me (my first real job was as an agricultural reporter in Tulare in the late 1980s) that a state with such unique agricultural characteristics should be a major exporter of dairy products, which can be and are produced in every state, albeit only barely in Alaska, which has just 300 milk cows. Let states that don’t have California’s climate but do have ample water and feed for the cows take over some of the dairy production so California farmers can focus on things that only they can grow, right?

It admittedly is a bit disconcerting that, as happened with the raising of poultry and pork before it, dairy farming is now shifting toward becoming a largely indoor undertaking. Dairy farmers are aware that this may be unsettling to non-farmers; the United Dairy Industry of Michigan put up an explainer earlier this year of “Why are cows in barns?” (Answers: to keep them from getting too hot, or cold, or sunburned.) At least from the photographic evidence I’ve seen, modern indoor accommodations for dairy cows look a lot more spacious and pleasant than those for chickens or pigs — if not quite as nice as lounging around in the shade on a California farm.

Lizza’s Esquire story about Nunes makes much of the contention that northwestern Iowa dairy farms like his family’s employ lots of undocumented immigrants. I can’t think of any reason why this would be less true in the San Joaquin Valley or any other dairy region, though. And as automation comes to the dairy industry and eliminates or at least significantly reduces the need for such labor, it will likely come first to big, indoor dairies in states with low unemployment rates — and Iowa and its neighbors have some of the lowest. The heart of America’s dairy industry is moving back toward the Midwest, and all in all, that seems like a reasonable enough thing for it to do.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.