Oil Will Still Be Sickly After the Virus

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Crude oil has had a grim start to the year, with prices hovering around $50 per barrel as China’s coronavirus epidemic shuts down swathes of the world's second-largest economy. A rebound akin to the one that followed the end of the SARS outbreak is unlikely this time.

Back in 2003, China was on a growth trajectory. The economy was also far smaller, accounting for less than 5% of global gross domestic product. Only about 10 in 1,000 people owned a car, a number that is now some 15 times larger. The only way for oil demand was up. This time, the coronavirus has slammed the brakes on an economy that in 2019 grew at its slowest pace in almost three decades. Car sales have fallen for two straight years, and manufacturing has been sputtering.

Worse, the crisis has coincided with a slowdown in India, another source of incremental oil demand, and hits a global market that was already oversupplied. By contrast, severe acute respiratory syndrome coincided with the Iraq invasion, which dented supply. Even an output cut by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries is unlikely to offer much more than damage control.

The impact of the epidemic has already been devastating, as the death toll rises to more than 400, including two victims outside China. There is an unprecedented quarantine under way. Provinces and cities accounting for two-thirds of China’s economy will extend their Lunar New Year breaks until at least next week. The resulting drop in demand for diesel, gasoline, jet fuel and the like means even state-owned Chinese refineries are cutting back, many unable to store more — in spite of a trade deal with Washington that requires more crude purchases, not less.

So far, China’s consumption is down by roughly a fifth, or about 3 million barrels a day, Alfred Cang, Javier Blas and Sharon Cho of Bloomberg News reported Monday, citing people with inside knowledge of the country’s energy industry. Eurasia Group analysts estimate the knock-on effect in the region could bring Asian crude demand down by 4 million barrels a day between the fourth quarter and the first three months of 2020, a 4% hit to global consumption.

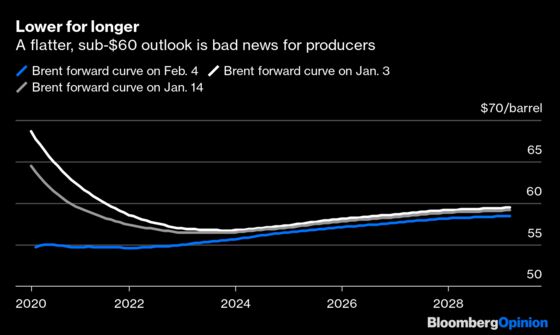

That’s a crash that suggests global appetite for oil, up just 1% last year and driven by China, will shrink this year. The market is reacting accordingly, with prices slipping into bear-market territory. WTI crude dropped below $50 a barrel and Brent, the global oil benchmark, was hovering around $55 Tuesday. The forward curve is no more encouraging for producers.

The bigger issue, though, may be less the depths plumbed now and more the duration of the trough. Recovery will conceivably be far slower than two decades ago. The length of the crisis is near-impossible to predict. Researchers at Hong Kong University have suggested infections will peak in late April. That would mean pain well into the second quarter.

The trouble then is twofold: First, China is short of economic momentum, absent more dramatic, long-lasting stimulus. Second, it will take far longer to get everything moving again owing to the ripple effect. Consider the supply chain disruptions, given clusters of auto and electronics manufacturing around Wuhan, which have already prompted Hyundai Motor Co. to suspend production in South Korea. That means fewer cars shipped, bought and eventually driven. Other sectors may follow.

With demand in the doldrums, OPEC will try to tackle supply. Officials are meeting in Vienna on Tuesday to consider responses that are likely to include an output cut, as my colleague Julian Lee has written. Recent efforts to reduce global output have struggled, and non-OPEC producers led by the U.S. are still adding barrels at a worrying rate. Consider the minimal impact of the Libyan oil blockade that has removed roughly a million barrels per day. A reduction of 500,000 barrels per day from OPEC, or even double that, could pale in comparison to China’s drop. It might still be a rare piece of good news for producers.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.