Coronavirus Is Worsening Delhi’s Air Pollution Crisis

The thick smog that blankets northern India with the approach of winter has a particularly grim ally this year: Covid-19.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The thick smog that blankets northern India with the approach of winter has a particularly grim ally this year: Covid-19.

Air pollution from the annual burning of rice stubble across the states of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Punjab is reversing the gains that gave the north of the country its cleanest air in two decades under lockdown earlier this year.

New Delhi’s air quality was running at levels considered hazardous for three consecutive days earlier this week, and the usual peak in pollution around the Diwali festival won’t even hit until Saturday. In Alipur in the north of the capital, an air quality index that conventionally tops out at 500 posted an off-the-charts reading of 851 Monday.

That’s particularly troubling given the evidence that air pollution is a major factor raising the risk of dying from coronavirus.

The decline in pollution and road accidents under lockdown meant that Delhi, paradoxically, saw an improvement in overall mortality rates in the early months of the pandemic, because the baseline of deaths from normal economic activity is already so high. With polluted winter weather, restrictions being further relaxed, and a two-month fall in death totals levelling off in recent days, India’s remarkably effective public health efforts against Covid are about to be put to the test.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Waves of smog as farmers burn off the residue of their monsoon rice harvest to make way for plantings of wheat and other winter crops have been common in recent years, but there’s a ready-made solution. The Happy Seeder, a tractor tool that allows crops to be sown directly without removing rice straw, was proposed as a miracle cure that could increase farmers’ profits as much as 20%, improve agricultural productivity, and eliminate the need for burning.

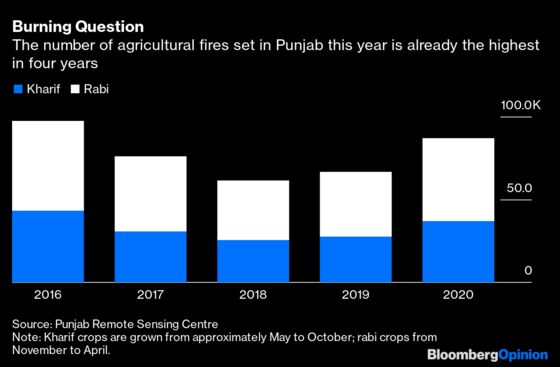

Sales of Happy Seeders have boomed thanks to government subsidies and heavy promotion, but it’s not been enough to end the haze. Despite reports of fewer fires in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh this year and a smaller area burned in Punjab, the sheer number of fires in that state — the epicenter of India’s seasonal crop burning — is already the highest since 2016, turning satellite monitoring images of the region into a sea of red.

Why hasn’t the Happy Seeder stopped this? It’s not been for any lack of demand. Sales of such advanced seeders are up 100-fold this year, according to Gurpreet Singh, joint head of marketing and sales at the Jagatjit Group of Industries, a farm-equipment manufacturer in Sangrur in Punjab. Unfortunately, that’s not enough to turn the tide, given the sheer volume of farms that need to convert.

“It will take time to educate the farmers of my region,” he said. “70% of customers are still using traditional methods.”

It’s possible that the pandemic itself is making matters worse. Farmers try to switch rice and wheat crops at this time of year as quickly as possible, but that depends on an army of more than a million migrant farmworkers from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh states to manage the work of burning and planting.

The coronavirus has kept many of those them closer to home in 2020, pushing the fire season further into the still, cool winter months when particulate smog settles most persistently over the north Indian plain.

Politics hasn’t helped, either. The government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi this year rammed through a law to allow more market-set pricing and remove the legacy of central planning from the country’s agricultural markets. The act has been controversial, with some of the fiercest opposition in precisely the northern states where stubble-burning is most severe, as my colleague Andy Mukherjee has written. Rural inflation has been running north of 7% for much of the year, the highest levels since Modi was elected in 2014 and well ahead of wage growth for most of the region’s agricultural workers.

Farmers who were reluctant to comply with government anti-burning orders in a normal year are even less likely to hold back now, according to ML Jat, principal scientist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in New Delhi.

On top of that, booming sales of Happy Seeders still aren’t sufficient to cope with the scale of the problem. While around 15,000 of the attachments have been sold so far, about 40,000 need to be in operation across the region to have a decent chance of eliminating stubble burning, said Jat. At that point, he predicts, northern India may finally start to see the pollution relief it’s been promised — but that’s probably another two years away.

It’s impossible to fix such a long-standing problem on a short timescale, said Jat: “The burning thing was not created overnight. It took decades.”

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.