Why Indonesia's QE Is Terrifying

Now that world’s largest central banks are buying trillions of dollars of bonds, emerging markets reckon they can experiment too.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Now that the world’s largest central banks are buying trillions of dollars of bonds, emerging markets reckon they can experiment, too. From Colombia to South Africa, developing nations are launching their own quantitative easing programs to stem the fallout from the coronavirus outbreak. But can these economies, known for capital flight and vulnerable currencies, pull it off?

Indonesia, with its current-account and fiscal deficits, has turned out to be a surprising forerunner in Asia. In late March, the government tapped the central bank to buy sovereign bonds directly in the primary market, a practice shunned for two decades. This would help fund a fiscal deficit that’s expanded to 5.1% from its long-established cap of 3%.

A large global investor base has boosted Indonesia’s confidence. In early April, when credit markets were still jittery, the nation raised $4.3 billion from its first so-called pandemic bond, which included a 50-year tranche — the longest-dated dollar debt issued in Asia. Last week, state-owned construction contractor PT Hutama Karya Persero sold a $600 million 10-year dollar bond that was fully guaranteed by Jakarta, another first. This bond was six times oversubscribed. Foreigners, who own about 30% of government debt, gobbled it up.

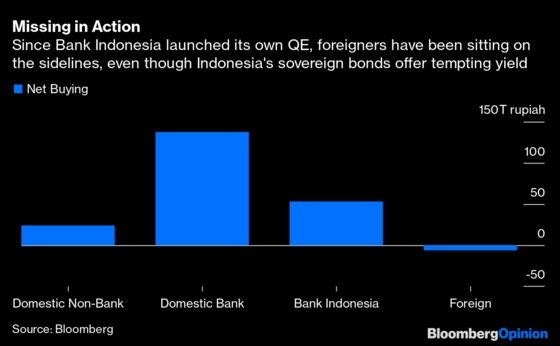

But barely two months into this new experiment, investors are sitting on the sidelines, even when the rupiah-denominated 10-year sovereign offers a real yield of 5%.

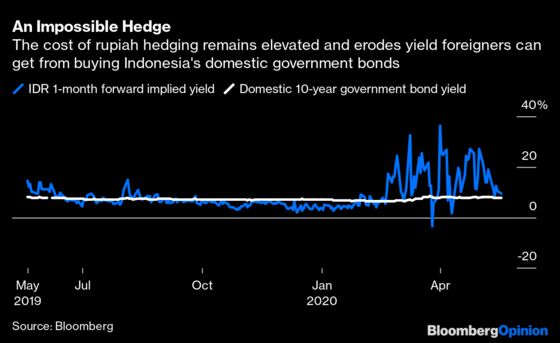

Most wouldn't dare buy these bonds naked, or without hedging rupiah exposure first. Bank Indonesia has tried hard to stabilize the currency, setting up a $60 billion swap line with the Federal Reserve, while negotiating another with China, its largest trading partner. It has also expanded the domestic non-deliverable forward market, allowing local businesses to meet their dollar needs. On Tuesday, the central bank kept its benchmark rate unchanged for the second month, surprising most economists. Nonetheless, the cost of hedging remains elevated, exceeding the domestic bond yield.

The rupiah’s hedging cost remains high in part because foreign demand is strong. A back test shows why. Over the last decade, long-term investors buying domestic sovereign bonds with a rupiah hedge would generate 4.8% annualized returns, analysis conducted by JPMorgan Chase & Co. shows. Buying without the hedge only improves returns by 1 percentage point, but almost doubles the risk. The best strategy is to hedge when the bond yield exceed rupiah forwards’ implied yield, and sit out otherwise, which is what’s happening now.

In other words, to entice foreigners back, Bank Indonesia needs to somehow bring down the cost of rupiah hedging first. That’s a tall order.

Take a look at Jakarta’s fiscal books, and all investors see is potential for a lot of money printing. As a result of the expanded deficit, the domestic sovereign bond supply will increase by almost 90%, forcing Bank Indonesia to buy another 350 trillion to 400 trillion rupiah ($23.6 billion to $26.9 billion) before the end of the year, estimates Goldman Sachs Group Inc. That would double the central bank’s holdings of such debt.

And this is just an estimate based on earlier rosy forecasts. The government said Monday its 2020 deficit would widen to 6.2% from 5.1% previously. New expenses could still spring up. For instance, an $8.6 billion bailout plan is now in the works to help struggling state-owned companies. Under President Joko Widodo’s first term, many fell to junk territory and balance sheets deteriorated as businesses financed big infrastructure projects. Already, lawmakers are berating the central bank for not printing money fast enough.

Developed nations are lucky. Thanks to the dollar’s reserve currency status, the Federal Reserve managed to rapidly expand its balance sheet to one-third of gross domestic product from around 20% at the end of 2019. Nonetheless, traders still worry that the U.S. government’s rapid debt build-up will spook foreigners, who own roughly a quarter of Treasuries.

Emerging markets don’t have the luxury of pursuing their own QE. During the taper tantrum of 2013, the rupiah lost 15% of its value in just three months after former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke floated the idea of ending bond purchases that May. Indonesia’s 10-year sovereign yield jumped as much as 3 percentage points. This wound is still fresh for investors and the threat of capital flight is real.

In the JPMorgan model, the investor usesone-month rupiah forwards and rolls her hedge monthly.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.