Why Vladimir Putin Suddenly Believes in Global Warming

Putin needs to go green quickly to stop permafrost from melting so that Russian oil & gas companies can keep pumping hydrocarbons

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Vladimir Putin needs to go green quickly to stop the permafrost from melting, so that Russian oil and gas companies can keep pumping the hydrocarbons that are warming the planet and making the permafrost melt.

Even I’m struggling with the warped logic of that one, but it’s the conclusion I’ve reached from Russia’s sudden ratification of the Paris climate accord and from reading the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Until now, climate change has been seen as a “good thing” for Russia — at least in part. Warming waters have opened up the Northern Sea Route across the top of the country and made it practical, if not necessarily economic, to search for and exploit oil and gas resources beneath the Arctic seas. Who remembers the Shtokman gas project?

Yet the warming that is opening up the Arctic seas may be starting to have a less beneficial effect on the frozen landmass of northern Russia, the heartland of the country’s oil and gas development and production.

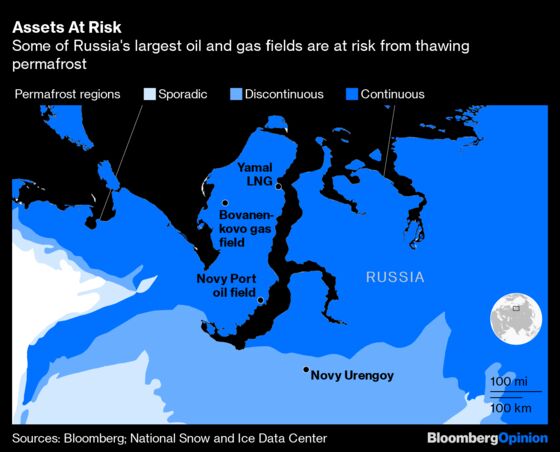

“Permafrost is undergoing rapid change,” says the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate report adopted by the IPCC last week. The changes threaten the “structural stability and functional capacities” of oil industry infrastructure, the authors warn. The greatest risks occur in areas with high ground-ice content and frost-susceptible sediments. Russia’s Yamal Peninsula — home to two of Russia’s biggest new gas projects (Bovanenkovo and Yamal LNG) and the Novy Port oil development — fits that bill.

The problem is bigger than those three projects, though. Some “45% of the oil and natural gas production fields in the Russian Arctic are located in the highest hazard zone,” according to the IPCC report.

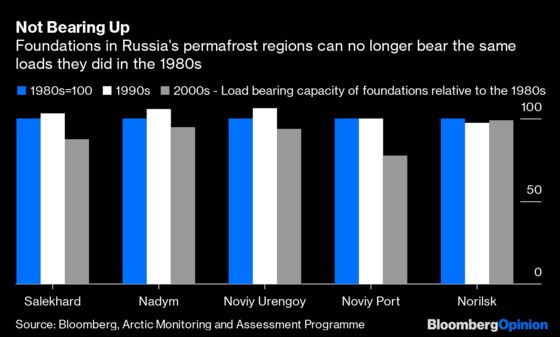

The top few meters of the permafrost, the so-called active layer, freezes and thaws as the seasons change, becoming unstable during warmer months. Developers account for this by making sure their foundations are deep enough to support their infrastructure: including roads, railways, houses, processing plants and pipelines. But climate change is causing that active layer to deepen, which means the ground loses its ability to support the things built upon it. The loss of bearing capacity is dramatic and it’s already well under way, as this chart shows:

Foundations in the permafrost regions can no longer bear the loads they did as recently as the 1980s, according to a 2017 report by the Arctic Council’s Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program. At Noviy Port the bearing capacity of foundations declined more than 20% between the 1980s and the first decade of this century.

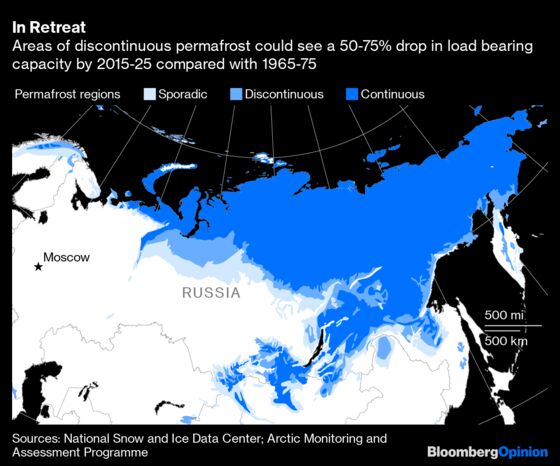

On the Yamal Peninsula the ground’s bearing capacity is forecast to fall by 25%-50% on average in the 2015-2025 period, when compared with the years 1965-1975. Further south, in an area that includes Urengoy (the world’s second-largest natural gas field) and much of Russia’s older West Siberian gas production, the soil could lose 50-75% of its bearing capacity, according to AMAP.

That may not be such a big problem for Russia’s newest oil infrastructure, which was designed with climate change in mind. The processing trains and storage tanks at Yamal LNG sit atop 65,000 piles driven up to 28 meters into the permafrost. These are kept cold by a so-called “thermosyphon system” designed to ensure that the soil’s load-bearing capacity is maintained throughout the project’s life.

Yet these assumptions depend on the models used to predict the extent of warming and permafrost degradation. What if they’re overtaken by an unexpected climb in temperatures?

“Near-surface permafrost in the High Arctic and other very cold areas has warmed by more than 0.5°C since 2007–2009, and the layer of the ground that thaws in summer has deepened in most areas where permafrost is monitored,” according to the AMAP. Under a high emissions scenario, “the area of near-surface permafrost is projected to decrease by around 35%.”

The Yamal Peninsula as a whole is slated to become one of the “three main Russian gas production centers with a potential annual output of 310–360 billion cubic meters of gas,” according to Russian energy giant Gazprom PJSC. That’s equal to half of all the gas produced in Russia last year.

Nevertheless, it may be too late to avoid much of the permafrost loss. AMAP says that even if greenhouse gas emissions were cut roughly in line with the targets in the Paris Agreement, that would only “stabilize near-surface permafrost extent at roughly 45% below current values.” Doing nothing would see an even greater loss and even more problems for Russia’s oil and gas producers. Is this the real reason for Putin’s sudden conversion?

--With assistance from Elaine He.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.