Why China Can’t Pull Up the World

Beijing’s stimulus has been targeted and domestically focused. That means it won’t do much to boost growth elsewhere.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The global economy is breathing a sigh of relief: China seems to be recovering from its months-long malaise.

The country’s growth numbers are improving. Proxies for infrastructure spending, such as fixed-asset investment, are looking brighter. Industrial production in construction-related sectors, including cement and steel, is rising.

This recovery isn’t as sturdy as it seems, though, and won’t do much to boost growth beyond China.

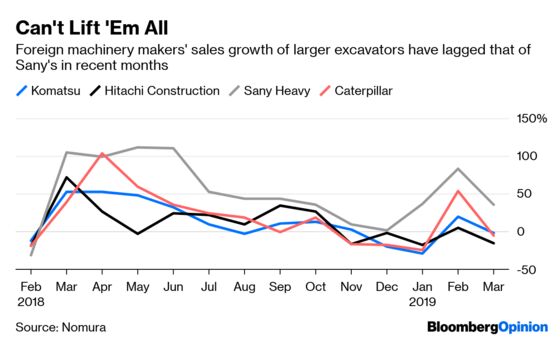

Consider what’s happening with the makers of construction machinery, typically a good gauge of infrastructure investment and demand. Sany Heavy Industries Co. and Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science and Technology Co. both posted strong sales volumes in the first quarter, with the country’s domestic excavator sales rising 24 percent during that period. Earlier this month, Sany said it expected core profits to rise more than 130 percent in the first quarter, citing higher volumes and demand from infrastructure projects. Several Chinese manufacturers have forecast as much as a 20 percent uptick in demand this year.

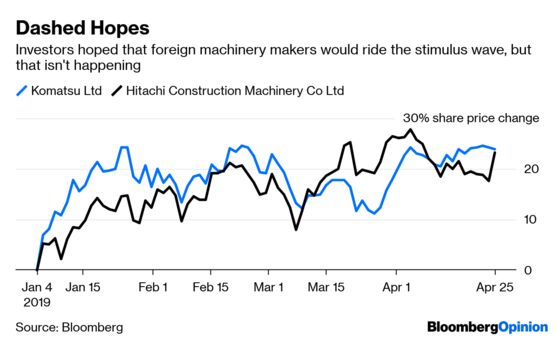

Curiously, foreign rivals such as Caterpillar Inc. and Hitachi Construction Machinery Co. aren’t getting the same boost. Both posted lackluster China sales and warned of a downbeat outlook in results this week. In an earnings call this week, Caterpillar’s chief financial officer said the global bellwether had lost mainland market share in the first quarter. Meanwhile, the Japanese company blamed China for a “downward trend” in hydraulic excavator sales, and flagged a deepening slump. On Thursday, the stock of 3M Co. collapsed 13 percent after the company said its sales fell because of China, a factor it had "discussed throughout the quarter." Results still came in lower than the company had anticipated and its outlook is uncertain.

So what explains their divergent fortunes?

For one thing, the latest surge of stimulus is targeted, and engineered to spur a domestic recovery. Much of the recent momentum was fueled by heaps of off-budget fiscal spending: Around 666 billion yuan ($99 billion) of special-financing bonds were issued in the first quarter — already around half of the last year’s total issuance. Even on-the-books expenditure grew 15 percent in the first quarter, much faster than the 6.5 percent for all of 2019. That’s an additional 300 billion yuan spent in the first quarter.

But Beijing is now fiscally constrained. At their China briefings with analysts in March, Komatsu Ltd. and Hitachi both cited delayed payments from local governments and tight funding as challenges. They also face pricing pressure as their Chinese peers get more competitive, which is eroding margins.

Meanwhile, China’s stimulus has been underwhelming. Tax cuts — at $50 billion in the first quarter — and consumption incentives for home appliances and autos aren’t moving the needle. Such measures simply rehash China’s old stimulus playbook. By most counts, underlying demand is still weak.

For China’s growth to be lasting — and strong enough to lift the global economy — companies and households need to spend. Signs of corporate outlays and reinvestment are few and far between. Consumption’s contribution to GDP remains the weakest since the data started, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc. The tax cuts may optically help profits but won’t shake a crisis of confidence: It won’t do any good for companies to produce more air conditioners if no one’s buying them. Credit conditions, meanwhile, still aren’t loose enough to support a widespread recovery and lenders remain unconvinced.

This has diminished China’s ability to lift not just foreign companies but foreign economies. South Korea’s gross domestic product shrank the most in a decade, according to data Thursday, contracting 0.3 percent in the first quarter from the previous period. The first quarter showed the biggest deviation from Chinese growth since the financial crisis, according Goldman. To some degree, South Korea’s slowdown, much like a recent downturn in German manufacturing, is a function of its sagging domestic economy. Still, manufacturing and construction, which are typically buoyed by Chinese industrial demand, dropped, too.

Until any of this changes, investors should get used to the idea that China won’t be able to pull the global economy up with it. It has far too many headaches at home.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.