Not Everyone Gets a Piece of China's $2 Trillion Pie

Regulators are reining in smaller brokerages to limit risk in the financial system. But consolidation is easier said than done.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China’s 14 trillion yuan ($2 trillion) brokerage industry is divided into two camps: What locals refer to as dragon heads – the biggest and fittest firms – and the laggards, what we’ll call the dragon tails.

China’s securities regulator recently formalized this distinction, taking steps to limit the scope of smaller firms’ services to traditional brokerage, advisory and underwriting. They will now be barred from riskier, more capital-intensive businesses such as over-the-counter derivatives and pledged-stock loans, the practice of offering shares as collateral (which can get messy when stock prices fall). The country’s minor players have gotten caught up in all kinds of unsavory practices that have led to defaults, market manipulation and worse – system meltdowns.

So time to cut off the tails. China’s brokerage industry remains surprisingly crowded, with a staggering 131 players, despite the paltry amount they earn. Last year, return on equity of listed brokers was just 2.5% compared with 7.8% globally, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Consolidation would go a long way toward helping regulators manage such a scattered industry.

Against this backdrop, it’s little surprise that even earnest bureaucrats in Beijing can’t keep track of all the sector’s shenanigans. As we’ve written, brokers’ asset-management arms have been major suppliers of shadow loans to risky private enterprises. Can’t get proper bank loans? No problem, acquire a brokerage for your financing instead. Xiao Jianhua – the founder of conglomerate Tomorrow Holding Co., who was abducted from Hong Kong’s Four Seasons Hotel in 2017 – owned a substantial stake in Hengtou Securities Co. The trouble in his business empire is far-reaching: In May, Xiao’s Baoshang Bank Co. became China’s first bank seizure in two decades.

With the helping hand of brokers, some companies also have been faking demand for their bonds. Not only does this practice distort pricing, it wreaks havoc in the interbank market. To pull it off, corporate issuers buy a sizable chunk of their own debt issuance through special funds, which brokers manage. That fund goes to the interbank market, a source of financing unavailable to non-financial firms, offering this bond as collateral. After the Baoshang seizure, however, borrowing costs soared as banks became unwilling to provide such repo financing to smaller brokerages. How can a big institution be sure it's trading with a genuine prop desk or one of these special funds standing in for a shady company?

As we saw with the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., counterparty risk can get ugly pretty quickly. The financial system hardens into a cement floor: Even fresh liquidity from the central bank can’t seep through. The People’s Bank of China can ask its state-owned banks to provide ample liquidity to the biggest brokerages – but that won’t help more than 100 smaller ones.

Consider, too, the sheer volume of stocks pledged for loans at brokerages. One year ago, a whopping 22% of listed companies pledged at least 30% of their shares for short-term loans. A weak market quickly turned into a bearish nightmare when pledged stocks edged close to margin calls. To keep things stable, regulators in January were forced to scrap an automatic threshold.

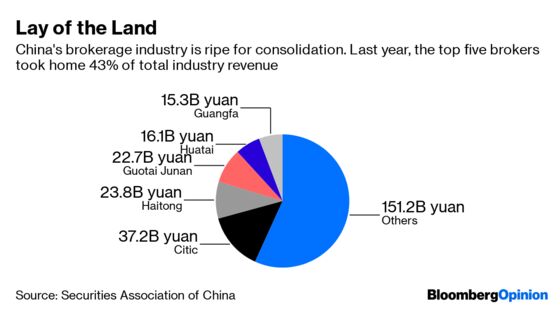

By now, China’s securities industry is ripe for consolidation. Last year, the top five brokers took home over 40% of the industry’s total revenue; more than 20 of the smallest players were loss-making.

But tossing out the smaller fish is easier said than done. Various arms of the government own many of the players, and bureaucrats wouldn’t dare to sell “national assets” below their book value. Of the 31 A-share listed brokers, government entities – from sovereign fund Central Huijin Investment Ltd. to lesser-known Hubei Energy Group Co. – on average have a quarter stake in brokers. In January, Citic Securities Co. raised eyebrows after planning to buy a loss-making regional securities firm from the Guangzhou provincial government for 13.4 billion yuan, or 1.2 times its book asset value.

It’s only natural to expect that China’s clever brokers will continue playing cat-and-mouse with regulators. But if Beijing’s brave enough to take on dragons, that could be a dangerous game.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.