China’s Banking Cleanup Needs a Bigger Mop

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China’s banking cleanup has moved into a fresh phase with the seizure of a small city-commercial lender. It’s far from clear that regulators have the right supplies to finish the job.

The central bank and the banking and insurance regulator are assuming control of Baoshang Bank Co. for one year because it poses serious credit risks, in the first government takeover of a lender in more than two decades. They’re bringing in state-controlled China Construction Bank Corp., one of the country’s largest lenders, to manage Baoshang’s business operations.

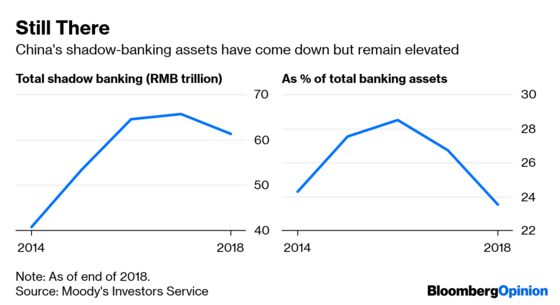

While a broader effort to rein in shadow-banking activity has been going on for several years, regulators haven’t assumed control of a bank in this way. In 2015 and 2016, they recapitalized lenders by injecting share capital while writing off or transferring troubled assets. They’ve also merged stronger with weaker banks, in transactions that had little commercial logic. These restructuring efforts were haphazard, mostly inadequate and didn’t address the issue of moral hazard.

So why the more forceful approach now? To begin with, there’s the concern of direct contagion. Baoshang’s assets of 576 billion yuan ($84 billion) are a drop in the ocean for a banking system with about 270 trillion yuan of assets. Yet a collapse, if allowed, could still threaten some disruption, particularly in the interbank market. The city lender had 193 billion yuan of borrowings and repurchase agreements outstanding, of which 169 billion yuan was due to other financial institutions, as of September 2017, the latest available data. It also holds large stakes in several village and other smaller banks. Liquidating those holdings would probably affect those lenders.

Baoshang has a tainted history: It was banned from some interbank trading for two years in 2013 and has had trouble raising capital. Contagion risks posed by Baoshang are among the highest for small city commercial banks, although still low within the system as a whole, according to an analysis last year by a researcher at Shandong University.

After the Baoshang takeover, retail and corporate deposits under 50 million yuan will be fully protected by regulators and the deposit insurance fund. There’s no guarantee that all corporate deposits above this notional value will get the same treatment. Construction Bank won’t bail out the lender or underwrite any of its risks.

Also, if regulators are worried about extensive contagion from a single bank, why rock the boat now? More worrying is that there are probably several other smaller lenders where problems are emerging, and regulators still haven’t found a way to manage them.

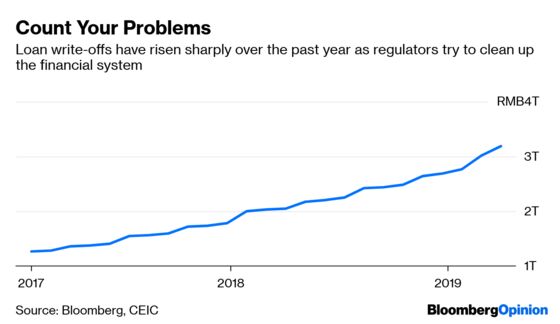

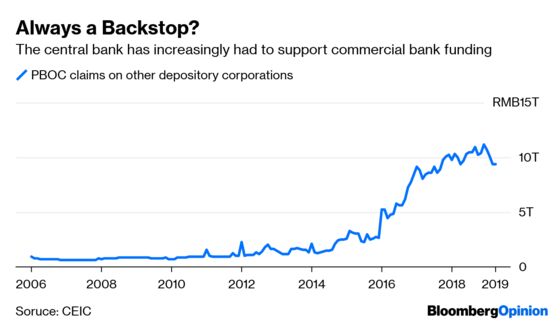

The timing speaks to the perceived urgency of the issue. With no big bank willing to absorb a smaller lender, the People’s Bank of China is still trying to get its arms around the problem. Bigger lenders have struggles of their own: Loan write-offs are piling up, and they’re being asked to rescue and finance China’s small and medium private enterprises.

Speculation in Chinese media has centered on the links between Baoshang and the Tomorrow Group conglomerate, whose former Chairman Xiao Jianhua has been in custody for more than two years. The group owns at least 70% of the lender through various subsidiaries and has been used as its piggy bank, Chinese financial website Caixin has reported. In a similar situation, Anbang Insurance Group – also seized by the government – held more than a third of Chengdu Rural Commercial Bank Co. and undertook several related-party transactions with the lender.

The bigger point, though, is that China still hasn’t found a sustainable way of bringing equity into its banking system. Earlier this month, the government removed a shareholding cap on lenders to allow consolidation and attract foreign capital. That doesn’t fix the problem either – who wants in at this point in the credit cycle? It’s likely to be a little too late.

Until regulators are clear about who’s on the hook for losses – between equity owners and bond holders at various levels – finding an efficient, market-based mechanism for the cleanup won’t be easy. Typically, capital injections after a bank is deemed unviable trigger a wipe-out of equity or a writedown of bonds. In Baoshang’s case, the central bank has said the lender will receive a liquidity injection, but further details have been sketchy. It’s unclear who will take any loss on the bank’s tier 2 capital bonds.

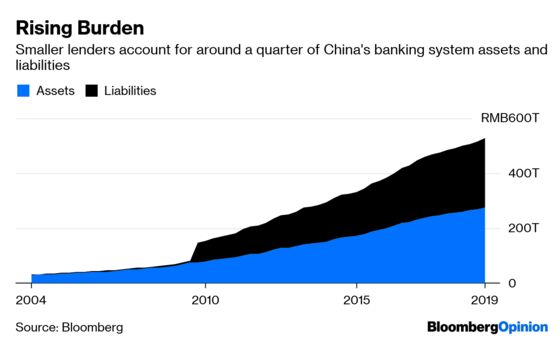

Ultimately, the government needs to be willing to take the pain, too. Smaller lenders such as Baoshang account for more than a quarter of system assets and liabilities, and it’s unknown how deep their problems go or how widely they may spread.

Beijing may end up needing much more than a mop and bucket to clean up this mess.

For example, Zhongyuan Bank Co. was created by a merger of 13 smaller and weaker city commercial lenders in Henan province.

In extreme conditions, like in the 1990s, the regulator shuttered banks such as Hainan Development Bank and three international trust and investment companies.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.