Cash Isn’t King When It’s Missing. In China, It May Be

The country is a potential gold mine for international credit rating firms, if they can adapt to local conditions.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Chinese debt is a potential billion-dollar market for international credit-rating companies. It’s also one riven with pitfalls.

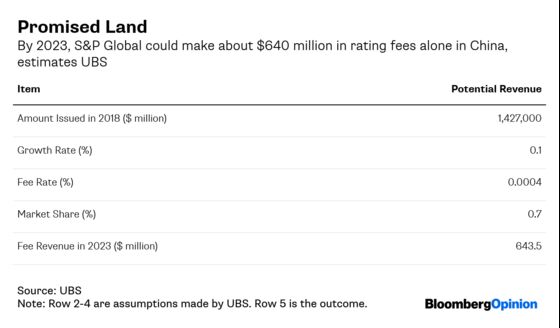

The world’s third-largest debt market can no longer be ignored. Chinese companies sold more than $1.4 trillion of bonds last year, more than was raised by their U.S. counterparts. Eager to attract more foreign investors, the government in January allowed the Beijing-based unit of S&P Global Ratings to offer corporate ratings services. It was the first time a company wholly owned by an international credit rating firm was able to score domestic Chinese corporate bonds, the New York-based company said.

The appetite is certainly there: Local companies with plans to sell offshore dollar bonds or establish overseas operations have been eager to forge relationships with the big three of S&P, Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings Inc. About two-thirds of 558 corporate respondents in an April survey by UBS Group AG said they planned to obtain a rating from an international firm within the next two years. A third aim to do it within a year; only 3% said they weren’t interested.

S&P could generate about $400 million from providing ratings alone, even if it charges only 4 basis points on the value of bond transactions – a big discount to the 6.95 basis points in the U.S., UBS estimates. Revenue could increase by hundreds of millions more if China’s corporate bond market continues to grow. That’s without factoring in sales of ratings data feeds and credit research.

Even as the foreigners tiptoe in, though, they’re finding the promised riches are buried under treacherous terrain.

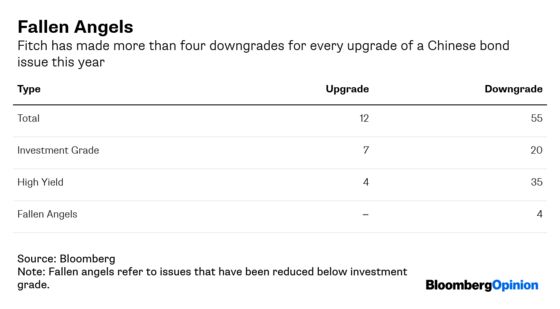

For every company that S&P upgraded in China this year, the firm has issued two downgrades (including placing of firms on credit watch). Fitch has issued 55 downgrades, more than four times its 12 upgrades: That compares with a ratio of less than two to one for Asia-Pacific as a whole. Region-wide, S&P has upgraded more companies than it’s downgraded.

Fitch’s actions included changing its mind on Tianjin-based commodities trader Tewoo Group Co. multiple times within a month. On April 9, the agency placed Tewoo, then assessed as investment grade, on negative ratings watch. It downgraded the firm to BBB-minus on April 15, and cut again by a rare six steps to B-minus on April 29.

The relative volume of downgrades points to the difficulty of assessing corporate creditworthiness in China. Granted, China’s trade war with the U.S. and the government’s deleveraging campaign have weakened balance sheets. But excessive debt or weak liquidity conditions aren’t the only drivers of corporate defaults. “Qualitative factors are playing an increasing role,” as S&P wrote in a June report.

Cash isn’t necessarily king in China, as bond traders have come to realize. Drugmaker Kangmei Pharmaceutical Co. said in April that it overstated cash holdings by $4.4 billion, due to an accounting “error.” Kangde Xin Composite Material Group Co., meanwhile, said its auditor could find no trace of a 12.2 billion yuan ($1.8 billion) bank deposit. Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch withdrew their ratings on the producer of high-polymer materials, which has issued dollar notes.

Ratings firms could use accounting metrics to spot red flags, S&P suggested in its report. These might include comparing a company’s interest income with its reported cash balance to see if there’s any discrepancy. Kangde Xin, for instance, earned only 167 million yuan on a reported balance of 18.6 billion yuan in 2017 – a return of less than 1%.

S&P’s idea is a start, but flawed, nonetheless. If a firm can allow billions of dollars of cash to go missing, it may not have any qualms about overstating interest income. Under China’s securities laws, companies are liable to a maximum fine of 600,000 yuan for furnishing false information.

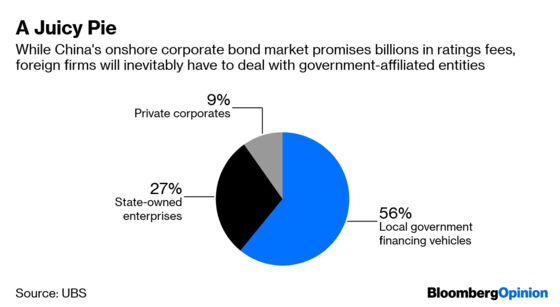

Providing credit ratings in China often means judging the financial health of municipalities – an unenviable task. Local government financing vehicles and state-owned enterprises still account for roughly 90% of the bond market. That means credit risk assessment invariably comes down to whether local governments are willing and able to provide support.

Tewoo, for instance, is 100% held by the Tianjin State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission. Fitch’s first downgrade this year was “driven by a lowering of Fitch’s internal assessment of the creditworthiness of Tewoo’s ultimate parent, the Tianjin municipality,” the ratings firm said. That shouldn’t have come as a surprise. Tianjin’s financial stresses have been well documented, and its tax revenue has been on the decline since 2017.

China could prove a gold mine for international rating firms. They just need to be careful it doesn’t collapse on them.

The UBS estimate is based on an assumption that S&P can capture 70% of China's market, in line with its presence in Asia over the last decade.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.