China and the U.S. Can’t Break Their Oil Market Codependency

You might think, from the way China and U.S. are working together to release oil, they had found one issue they can cooperate on.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- You might think, from the way China and the U.S. are working together to release crude from their strategic petroleum reserves and take some of the heat out of the oil market, that the world’s two biggest energy consumers had found one issue they can cooperate on.

“Taking measures to address global energy supplies” — in retrospect, clearly a reference to the reserve releases that followed — was one of few solid points of agreement in last week’s virtual summit between presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping.

Nonetheless, it remains an uneasy relationship. Take Khalifa, a port on the oil-rich shores of the Persian Gulf where China’s state-owned Cosco Shipping Co. has been building a $738 million container terminal with the government of Abu Dhabi. U.S. intelligence agencies discovered China was secretly establishing a military facility at the port and lobbied the UAE to halt construction, the Wall Street Journal reported last week, citing people it didn’t name. That would represent an extraordinary incursion in a region where the U.S. is the only major external military power. (Its allies the U.K. and France also have small bases in Bahrain and the UAE.)

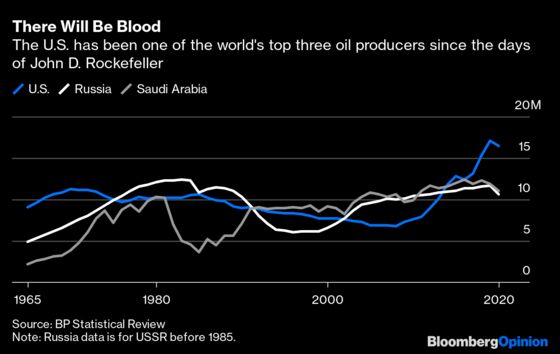

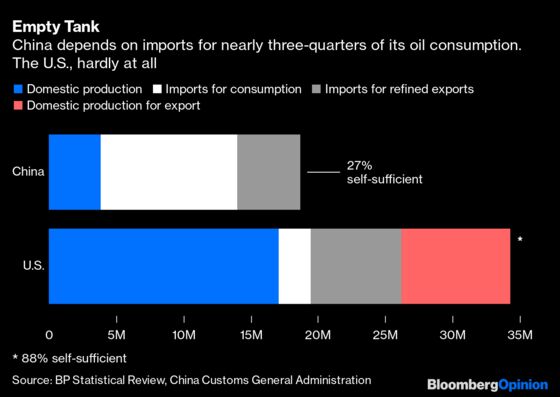

It’s not hard to see why Beijing would want a more secure foothold in the Gulf. The U.S. has been one of the world’s three biggest oil producers since the 19th century and could, in a pinch, be self-sufficient. China, on the other hand, imports nearly three-quarters of its oil, about 60% of the total by sea.

The regime in Beijing has an existential dependence on the long supply lines carrying crude from the Gulf to its eastern ports — and the security detail for that trade is provided by the U.S. Navy. If the two nations ever came to blows (in a conflict over Taiwan, for example) it would be relatively easy for Washington to blockade China’s energy supplies in the Straits of Hormuz, Malacca and Singapore. That could bring the entire country — and most importantly, the power source for its war machine — to a standstill.

Great power conflict has been long been driven by energy and transport. Britain’s naval blockade in World War I turned the war in its favor by cutting Germany off from imported nitrate fertilizers, leading to widespread calorie deficits and hunger. Japan’s colonization of Manchuria and then Southeast Asia two decades later aimed to replace its previous dependence on American oil. Hitler invaded Russia in part to capture the oilfields of the Caucasus and fix the Wehrmacht’s outdated dependence on horse-power rather than motorized transport.

That’s the best explanation for Washington’s continued obsessive involvement in the Middle East, a region in which it has few strategic interests proportional to the vast sums invested over the decades.

“The U.S. predominance in the Gulf is a key element of its status as the predominant global power,” said David Brewster, a senior research fellow at the Australian National University’s National Security College who focuses on the Indian Ocean. “If the U.S. weren’t there then the Chinese would be there, and that would destabilize the whole region.”

Understandably, Beijing doesn’t appreciate having America’s hands at its throat in this way — but it’s stuck with it, unless new zero-carbon technologies can replace crude in both civilian and military uses.

Key elements of China’s foreign and defense policies over the past decade make most sense as an attempt to redress the power imbalance. The Belt and Road Initiative, with its ports in Tanzania, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Myanmar, gives Beijing a footprint in the Indian Ocean that could one day be repurposed to offset its critical shortage of military refueling and supply facilities. China’s only overseas military base, in Djibouti at the gates of the Red Sea, could serve a similar purpose.

Pipelines through Myanmar, a railway across Malaysia, and incentives for rail transport through central Asia all reduce dependence on the chokepoint around the Strait of Singapore. China’s recent increased anti-piracy activity in the Indian Ocean and aircraft carrier construction all suggest ambitions to become a blue-water naval power, able to operate far from its own shores and secure distant sea lines of communication essential for its own survival.

It’s a dangerous game. China is unlikely to ever be a competitive fleet in the Indian Ocean, said Brewster: “In the event of a major shooting match, it would be immediately cut off from home ports and would be highly vulnerable.” Even so, great power attempts to insure themselves against rivals’ control of the seas have historically precipitated conflict as much as they’ve averted it, as with the Anglo-German arms race before World War I and Japan’s pre-emptive strike against Pearl Harbor.

That’s no less the case now. Any incremental shift from the U.S. to China in control over Asia’s crude supply lines would alarm Washington’s other oil-dependent allies Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, quite as much as it gives comfort to Beijing. India, the world’s third-biggest crude importer and the natural hegemon in the Indian Ocean, may also find it’s unable to sit idly by.

Much as this uneasy status quo may annoy foreign policy experts in the U.S. who’d like to see the nation pivot away from the Middle East, and alarm their peers in China who fear having their national security under the thumb of the Pentagon, for the moment it’s the best we’ve got. Cooperation between the great powers over the release of their strategic petroleum reserves might not transform the oil market. The alternative to cooperation, however, is far worse.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.