Central Banks Don’t Have the Answer and Markets Know It

The struggle to sustain growth leads market commentary. Plus bullet-proof bonds, currency wars and more.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It was hard not to come away depressed after watching European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s Thursday press conference, during which he basically admitted that policy makers are unable to reverse the rapid weakening in the global economy. Draghi said the euro-zone economy will now expand only 1.1 percent this year, a drop of 0.6 percentage point from forecasts just three months ago. He also pledged a package of new loans for banks, additional stimulus that ought to have been reassuring for markets.

But in a sign of the hopelessness of it all, stocks tumbled, and not only in Europe. At one point, the MSCI All-Country World Index fell as much as 1.18 percent in its biggest decline in more than two months. European banking stocks, which should have benefited most from the ECB’s pledge of new funds, fell as much as 2.58 percent as measured by the STOXX Europe 600 Banks Index, bringing its decline since late 2009 to 40 percent. To a growing number of market participants, that’s the problem. It’s almost impossible to have a healthy economy without a healthy banking system, but most of the ECB’s stimulus measures in recent years have been aimed at boosting inflation, which hasn’t worked. “It’s important to interpret what the ECB is doing as NOT further accommodation,” Bleakley Financial Group chief investment officer Peter Boockvar wrote in a note to clients. “It is in fact contractionary policy because they are damaging the income-producing ability of its banking system, which is the life blood of any economy.” And here’s the kicker: Some ECB Bank policy makers consider the downgraded growth forecast for 2019 still too optimistic, Bloomberg News reported, citing people with knowledge of the matter.

The issues facing the euro zone aren’t isolated. The U.S. Federal Reserve, Bank of Canada and Reserve Bank of Australia are among central banks that have taken a dovish turn in recent weeks as evidence of a synchronized slowdown builds. It’s not encouraging that the global economy is still struggling a decade after the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. And that’s after central banks pumped trillions of dollars into the financial system. As of February, the collective balance-sheet assets of the Fed, ECB, Bank of Japan and Bank of England stood at 36.3 percent of their countries’ total GDP, up from about 10 percent in 2008.

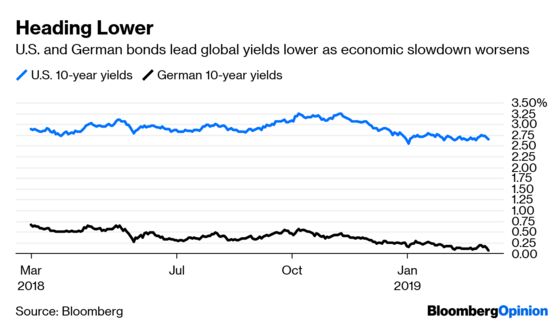

DON’T BET AGAINST BONDS

The other takeaway from Draghi’s press conference is that it’s a fool’s game to bet against bonds. Yields on most all major sovereign debt fell on Thursday. Those on 10-year German bunds fell to 0.067 percent, their lowest since 2016. With about $9 trillion of securities paying negative yields, the global government debt market has been called the history’s biggest bubble. But the thing is, people have been calling for the bubble to burst for years now. And despite periods of weakness, the bond market has shown extreme resilience. The way central bankers are talking these days, that’s unlikely to change. The Fed has hinted that it will stop shrinking its balance sheet this year, which should alleviate any of the pressure weighing on Treasuries. Heck, some Fed officials in recent weeks have talked about fine-tuning their extraordinary monetary policy measures in case they need to employ them again, including capping yields! To understand how important low yields are to global markets, recall that the correction in stocks in the fourth quarter was initially triggered by rising bond yields. That led to evidence the global economy was too fragile to handle the spike in yields, leading to concern about a slowdown that we’re seeing now. And as the strategists at Richardson GMP point out, this year’s rebound in stocks came after bonds yield fell. “With lower bond yields for longer, you get this sort of Goldilocks environment,” the strategists wrote in a research note Thursday. “No inflation, low yields, some growth, everyone is happy.”

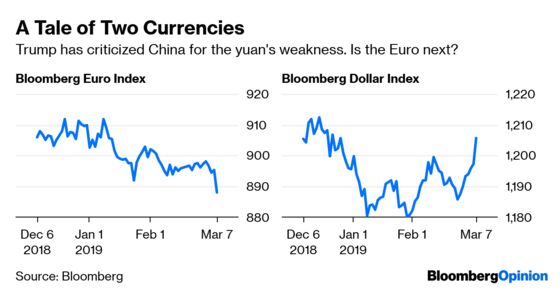

THE CURRENCY WARS MAY BE BACK

Back in 2010, when major central banks began debasing their currencies by slashing interest rates to near zero – or even below – and printing money to buy financial assets, Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega famously labeled the moves nothing less than a "currency war." Such talk died down in 2017 and much of 2018 as the focus turned to a synchronized global economic recovery, but it’s possible that the ECB’s move on Thursday will revive the wars. The Bloomberg Euro Index, which measures the currency against its major peers, plunged as much as 0.86 percent to its lowest level since mid-2017. Draghi’s “obsession with generating higher inflation and the scorched earth policy he took to get there has now left the ECB without any effective tools to deal with any economic challenges,” Boockvar added in one of his notes. That leaves a weaker euro as the only viable option to boost the economy. But the flip-side of a weaker euro is a stronger dollar, which U.S. President of Donald Trump has railed against several times in recent years, including this past weekend. Nevertheless, the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index rose as much as 0.70 percent Thursday, reaching its highest level of the year. The measure of the greenback is up about 7 percent over the past 12 months, compared with a decline of about 6 percent for the gauge of the euro. The latest currency moves may become a central part of trade talks between the U.S. and the European Union, much as the yuan has become with the trade talks between the U.S. and China. If so, then get ready for a lot more currency volatility.

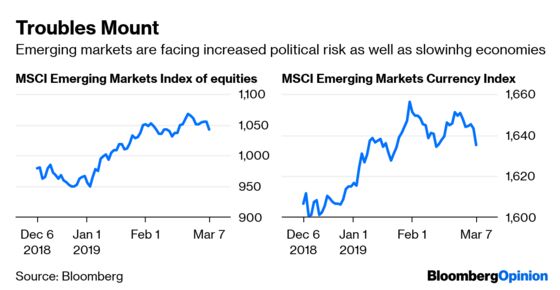

EMERGING MARKETS TAKE A HARD HIT

A stronger dollar has all sorts of implications for global markets. For example, if investors believe the greenback is on the cusp of a prolonged upswing, they may be more inclined to take money out of, say, emerging market assets and put it into dollar-denominated assets. That helps explain the 1.15 percent tumble in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index of equities, which exceeded the 1.0.87 percent drop in the MSCI All-Country World Index of stocks. An MSCI index of emerging-market currencies fell 0.29 percent. A stronger dollar comes at a tough time for emerging-market investors, which are navigating a period of increased political risk as China takes a more aggressive stance on the global stage and India gets into a military spat with neighboring Pakistan ahead of elections in the world’s largest democracy. A custom measure of risk, based on GeoQuant indexes for ten major developing countries, has increased for 23 straight weeks, climbing above a previous high triggered by the U.S.-China trade dispute, according to Bloomberg News’s Srinivasan Sivabalan. In China, diplomats are lashing out, accusing Canada of “white supremacy,” blasting Sweden’s “so-called freedom of expression” and claiming that Trump is making the U.S. “the enemy of the whole word.” India’s escalating military tensions with neighboring Pakistan and rising unemployment mean Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s re-election in May is no longer a given.

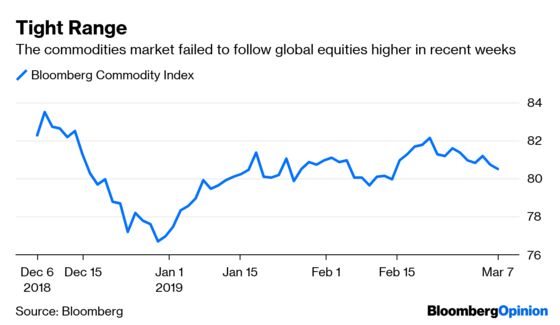

COMMODITIES MARKETS ARE STUCK

The commodities market isn’t just sensitive to the economic cycle, but to the fluctuations in the dollar as well. That’s because most raw materials are traded in the greenback, which means that a rising dollar tends to make commodities look more expensive. So it makes sense that the Bloomberg Commodity Index fell to a three-week low on Thursday as the dollar appreciated. In fact, the commodities market has joined the bond market in flagging concerns for some time, basically trading in a tight range since mid-January even as global stocks soared. Of course, commodities are also heavily influenced by things like supply and the weather. Oil is one area where supplies are abundant, helping to restrain prices. For example, an Energy Information Administration report Wednesday showed the biggest U.S. crude stockpile build since January last week. Wheat is another area where supplies are abundant. Favorable weather from Russia to North America has led to optimistic crop forecasts for the coming season and, in its first outlook for 2019, the United Nations said global output may climb 4 percent, according to Bloomberg News’s Megan Durisin and Volodymyr Verbyany. Wheat prices fell 2.61 percent Thursday, bringing the year-to-date decline to 14 percent.

TEA LEAVES

The U.S. employment report for February will be released Friday, and this might be the rare time when the headline data takes a supporting role. The government is forecast to say that the economy added 180,000 jobs last month, following a January’s 304,000 gain. The January number blew away the median estimate of 165,000. But we now know that the data collection efforts were less than optimal given the government shutdown starting at the end of December and lasting through January. Recall that December’s jobs report number was originally over 312,000 before being revised down to 222,000. ”This 90,000 downward revision for the December data was the largest - either negative or positive- adjustment from one month to the next since a 94,000 downward revision for the February 2017 data,” BNY Mellon currency and macro strategist John Veils wrote in a research note Thursday. “Before that, you’d have to go all the way back to the depths of the global financial crisis - December 2009 to be exact - to get a comparable downward revision, although there have been similarly large upward revisions in more recent years.”

DON’T MISS

Why ECB Followed the Fed's Flip-Flopping: Mohamed A. El-Erian

ECB Takes First Step to Admitting Its Mistake: Marcus Ashworth

How to Tell When Federal Deficits Cross a Line: Stephanie Kelton

OECD Spares the World's Most Popular Scapegoat: Daniel Moss

Drama Erupts in Tiny Corner of High-Yield Munis: Brian Chappatta

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.