Brexit Realism Hasn’t Erased Brexit Divisions

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Having dominated U.K. politics for the last two years, you might think that all of the news about Brexit would have led some Brits to change their minds one way or the other. Indeed polls have shown that something like three-quarters of Brits think that their government is handling the U.K.’s exit from the EU badly.

Yet when it comes to the big picture questions of whether Brexit was the right or wrong decision, or how people would vote in a hypothetical rerun of the first vote, the movement has been glacial.

Last week, a lot of excitement was generated when a NatCen poll on a hypothetical second referendum put the Remain side ahead 59 to 41. Most other polls, however, have suggested that such a vote would be considerably closer. And on the question of whether to hold another referendum, the answers vary considerably depending on how the question is asked, with those who voted for Brexit in 2016 strongly opposed when it’s clear the vote would potentially keep U.K. in the EU.

Yet on some key issues, there is more material change.Much commentary around the 2016 vote has attempted to pin the result on individual factors. While the vote was more complex than this, there can be little doubt that hostility to high levels of immigration was a key driver of the Leave vote. It’s significant that the NatCen poll, among others, found a softening of public attitudes to immigration, both on its own, and when asked as a trade off against freer trade with mainland Europe.

The other key shift has been in the perceived economic consequences for Brexit. Though evidence of the link between voters’ own economic circumstances and Brexit is weaker than commonly assumed, individual perceptions on how Brexit would affect the economy were a key predictor of how they would vote. That may, of course, be a case of political preferences driving economic expectations rather than the reverse, but correlation between the two means that the shift still matters.

On that point, NatCen also found that the proportion of Leave voters expecting a positive economic impact has fallen from around 90 per cent at the time of the vote to around half now.

Of course, it’s the British government that’s negotiating with the European Union, not the U.K. electorate. But politicians will nevertheless be mindful of what the public wants. A closer look at what the public wants gives some indication as to why compromise has been so difficult. My firm, Number Cruncher, polled the Brexit views of 1,036 eligible voters last month.

We first asked whether people thought the Brexit vote was right or wrong. The result was a four-point lead for “wrong,” with 47 percent to 43 percent for “right,” and 10 per cent undecided.

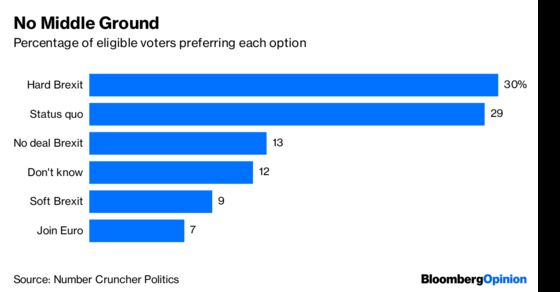

We asked people which of five options, using descriptions rather than the technical terms, would come closest to their preferred relationship between the U.K. and E.U.: “If you could choose from the following, which would come closest to your preferred relationship between the U.K. and EU?” The options were: Out of the EU with no deal on withdrawal or trade (a “no deal Brexit”); out of the EU with a basic deal, but with full control of the migration of people (“hard Brexit); out of the EU but inside the single market and without restrictions on migration (a “soft” Brexit or the so-called Norway option); in the EU on the same terms as the U.K. has had until now (the status quo); In the EU and a member of the single currency; don’t know.

Some 30 percent opted for a “hard” Brexit, just barely more than wanted to stay in the EU on the current terms (29 percent). The hardline options of a “no deal” Brexit (13 percent) and joining the euro (7 percent) were some way behind, as was the “compromise” soft Brexit option (9 percent).

These results highlight two conundrums. First, while Brits are likelier to think that Brexit is the wrong decision in our poll, their preferences split 52-36 in favor of scenarios that would still involve the U.K. leaving.

Second, although the median voter (excluding the 12 percent who answered “don’t know”) is a soft Brexiter -- as you might expect given an original 52-48 result -- soft Brexit itself is not wildly popular, being the first choice of fewer than one-in-10 eligible voters. Though it would represent a compromise, staying in the single market would retain many key features of EU membership, making it unpopular with Brexiters, but would still mean being out of the bloc and without a seat at the table, which is unpopular with those opposed to Brexit.

Prime Minister Theresa May’s task, then, is to square a circle that looks as round as ever. The compromise option appears to fall between two stools -- opposition to her Chequers plan has been forceful from both pro- and anti-Brexit camps in Westminster, and it seems the public too.

The politicians on both sides of the debate and both sides of the English Channel may well be able to reach an agreement that all sides can swallow. Just don’t expect the voters to agree with each other any time soon.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Therese Raphael at traphael4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matt Singh runs Number Cruncher Politics, a nonpartisan polling and elections site that predicted the 2015 U.K. election polling failure.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.