Brexit Used to Mean Brexit. What Does It Mean Now?

By now, everyone should know exactly what that terms means, but that’s the problem – nobody really knows.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Theresa May won the U.K. premiership by saying that: “Brexit means Brexit.” This comment, along with some fratricidal maneuvers among the Brexiteers within her Conservative party, helped ensure that a politician who had supported staying in the European Union would be given the job of taking the U.K. out. But the continued Shakespearean bloodletting among the Brexiteers is getting in the way of working out what kind of a deal might be acceptable to those who have asked for it.

Meanwhile the studied vagueness of “Brexit means Brexit” no longer sounds decisive. By now, everyone should know exactly what Brexit means, but that’s the problem – nobody really knows. Add the disastrous miscalculation of calling a general election last year, which left Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party holding the balance of power, and we have the U.K.’s dreadful current political mess. And although there were only two options at the Brexit referendum in 2016 – stay or leave - there are now several more, none of which seem capable of commanding a majority in the U.K., and most of which would be unacceptable to the rest of the EU.

Simplifying the issue is always dangerous (just ask David Cameron, the prime minister who decided the referendum was a good idea). Much depends on the critical issue of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. This matters because if the U.K. is to leave the EU’s customs union, as Brexiteers insist, then the border must become a “hard” border, with standard customs checks. Northern Irish politicians won’t stand for this. The obvious alternative, of leaving Northern Ireland within the customs union but removing the rest of the U.K., means introducing the concept of a border through the Irish Sea, which is unacceptable to Northern Irish Unionists. The issue of the Northern Irish border barely ever arose during the referendum campaign, when the DUP was an enthusiastic proponent of Brexit.

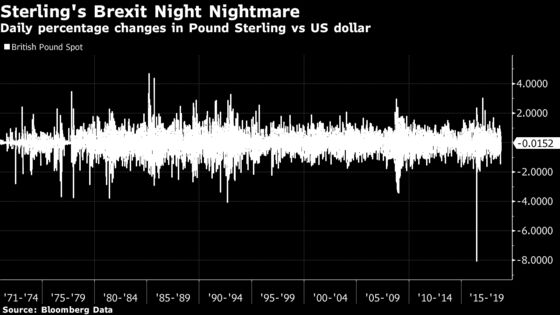

Sterling received a gigantic re-rating on referendum night. Traders had expected a different result, and as a result the pound suffered its worst one-day decline against the dollar since it was allowed to float in 1971. The fall was more than double anything that had previously been seen. There is no need to mark where the referendum happened on this chart:

What is startling, when looking at either the currency or at U.K. stocks, is that that one frantic re-rating in sterling in the summer of 2016 has stood the test of time very well. Neither U.K. stocks nor the pound have suffered much more damage since then. This is how the FTSE 250 index of U.K. stocks has performed compared with the rest of the world over the last five years:

It is only in the last few weeks that the FTSE 250 has dropped meaningfully further behind the rest of the world’s stock markets compared with its position immediately after the referendum. There is a similar outcome if we look at the pound on a trade-weighted basis as calculated by Deutsche Bank AG:

On this basis, the pound remains almost 20 percent weaker than its 2015 peak, but it is also some 5 percent stronger than at its recent low in October 2016, when May first unveiled her plan to seek what is now known as a “hard Brexit,” in which the UK left the EU without attempting to stay in the EU’s tariff-free single market, in a speech to the Conservative party’s conference.

The pound’s resilience is remarkable given the great level of uncertainty. This is in large part because the issues now rest almost entirely on U.K. politics. Broad outlines of a deal have been thrashed out. The risk that the EU, a cumbersome body if ever there was one, rejects a final deal are not trivial, but by far the greatest risk is that no deal can pass the U.K. parliament. Foreign-exchange strategy notes on sterling are now almost entirely taken up with the mathematics of Westminster.

So, avoiding the technical niceties of trade and immigration policy, the source of greatest uncertainty is the U.K.’s parliament, where four broad political options remain possible:

- It agrees to a “deal” on its future relationship with the EU;

- It goes ahead with a “no deal” option, with future trading relations with the EU bloc set by World Trade Organization rules;

- It votes down a deal and a general election (to vote in an entirely new House of Commons) is called;

- It votes down a deal and another referendum on Brexit (known as a “People’s Vote” to its supporters) is called.

There is great difference between these options, and great political risk. But neither the stock market nor the foreign-exchange market appears to see the situation as much more alarming than it was at the end of June 2016. And currency strategists are happy to come up with explanations.

Simon Derrick, veteran foreign-exchange strategist for BNY Mellon in London, pointed out to me that all of those options have been clear for some weeks. Also, none of them are as clear-cut in being “positive” or “negative” for the pound as they might at first appear. Another referendum might not necessarily even have the option of staying in the EU explicitly listed in the ballot. And if it does, it is still far from clear that Britons would change their mind and vote to stay in. The behavior of EU negotiators in recent months has done nothing to make continued membership look more appealing to British voters.

As for a general election, it could result in an even worse mess with nobody able to control a governing coalition. It could also result in a majority for the Labour party under Jeremy Corbyn, which would not sit at all well with international capital markets.

Thus on this line of reasoning there really are no particularly positive outcomes available – given that the prospect of a workable compromise has been growing more distant for weeks. Everyone knows this, and so the markets may have taken more account of political risk than many realize. The strong likelihood remains that there will be a British exit from the EU, and that is what markets have been pricing for a while. Another referendum or a general election would increase uncertainty and not necessarily help the pound.

This does, however, lead to the implication that sterling could have further to fall if the British political establishment’s bid at self-destruction steps up yet again, and the country is faced with a referendum or election. As George Saravelos, a currency strategist at Deutsche Bank puts it:

The risk of a near term political crisis - either a leadership challenge from Brexiteers - or a breakdown in the DUP/Conservative political agreement - is underpriced. We argued last week that the market is pricing a minimal probability of a no deal outcome. While we still anticipate a deal being ratified by the UK parliament by year-end, the risk we are wrong is greater than current market pricing suggests.

Put differently, there is still a risk that the pound falls significantly; there is very little chance of some deal that radically improves it. And the referendum also provided us with a rather worrying sign that the foreign-exchange market is not always good at judging U.K. politics.

Bad Days for Banks

Amid the excitement in the U.S. stock market, one trend is clear: financials are badly underperforming, and they are doing so despite what appear to be respectable third-quarter earnings by U.S. banks and higher bond yields. It is hard not to view this as a sign of a serious lack of confidence.

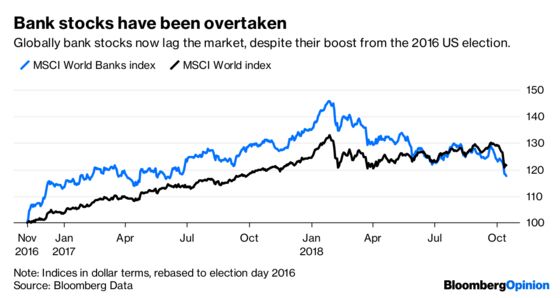

Globally, bank stocks roared ahead of the rest of the market following President Donald Trump’s election victory in 2016. The belief was that this would mean more growth and higher interest rates – perfect news for banks that had been in the doldrums. Any regulatory changes would merely have been “gravy.” But since the equity market correction in February, developed world banks have suffered a severe sell-off, with the MSCI World Bank Index now down 19.5 percent from its peak. It has given up the last of its gains compared with the market as a whole in the last few days, and is now lagging behind the MSCI World Index since the election almost two years ago.

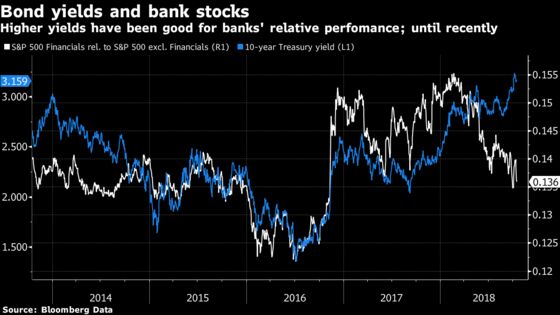

It is difficult to explain this away in terms of the trajectory of interest rates. The chart below shows the relative performance of the S&P 500 Index financials sector relative to the rest of the S&P 500 going back five years, compared with moves in bond yields. It was long taken as axiomatic that low bond yields were bad for banks, as they limited the profits that could be made from lending. Bank stocks and the 10-year Treasury yield even bottomed on the same day, in the summer of 2016 in the wake of the Brexit referendum.

Higher bond yields have done nothing to help bank stocks since the equity market correction earlier this year, however. Further increases in benchmark 10-year Treasury note yields have been greeted by severe under-performance for U.S. bank stocks, which has been matched by poor performance for bank stocks in the rest of the world.

One explanation might be that the yield curve has flattened. This diminishes the potential profits to be made by borrowing at short-term rates and lending for the long-term. But the yield curve had been steadily flattening since early 2014, and this did not thwart banks from enjoying their strong rebound after Trump was elected president in November 2016.

Another worrying sign is that it is precisely the big financial institutions deemed to be “GSIFIs” (global systemically important financial institutions) by international regulators that are performing worst. Ian Harnett, the chief investment strategist at London’s Absolute Strategy Research, points out that an index of the global banks treated as GSIFIs s was down 23 percent from its 12-month high in dollar terms, even before the U.S. banks started to release third-quarter results on Friday. Most of them, led by Germany’s Deutsche Bank, which is down some 46 percent from its recent high, are firmly in bear market territory.

It is hard to come up with any reassuring signs in this. The fact that tightening financial conditions seem to be causing so much angst about the health of big systemically important banks is worrying, and does suggest that the Federal Reserve should slow down. And while banks continue to create that amount of worry, it will be hard for stock markets to show a strong recovery.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.