Bond Traders Have the Fed Firmly on Their Side

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Faced with an extraordinarily difficult situation, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell gave bond traders exactly what they wanted in the central bank’s latest monetary policy decision.

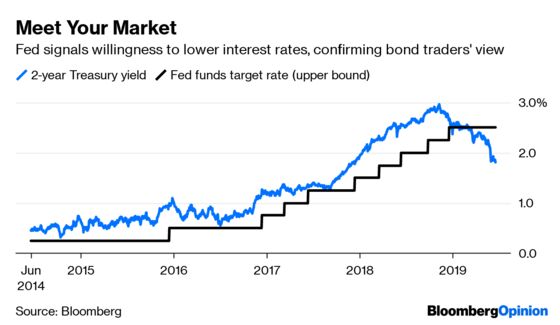

While the Fed left its benchmark lending rate unchanged in a range of 2.25% to 2.5%, changes to language in the Federal Open Market Committee’s statement, like removing the word “patient” and pledging to “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion,” pointed to reducing interest rates in the near future. One voting member, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, even dissented in favor of a cut. On top of that, the “dot plot” showed the median projection among policy makers was for lowering interest rates at some point before the end of 2020.

The reaction in the world’s biggest bond market was swift, even though a Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey released Tuesday found that being long U.S. Treasuries has become the world’s most-crowded trade for the first time ever. Two-year U.S. yields dropped 10 basis points after the announcement to 1.76%. The day of the Fed’s last meeting, it was 2.3%. Benchmark 10-year yields also fell toward the 2% level, which hasn’t been breached since around the time Donald Trump was elected president. The yield curve steepened sharply.

On top of validating dovish wagers among bond traders, who had priced in 2.5 cuts for 2019 ahead of the decision, the Fed’s latest shift is also a victory for Trump, who has been pounding the table for lower interest rates and whose White House, as Bloomberg News reported, in February explored the legality of demoting Powell. (He said “let’s see what he does” when asked later on Tuesday if he still wants to demote him.)

This is probably not the outcome that Powell wanted but the one he felt he had little choice but to deliver. Just consider what has happened since the last Fed member spoke on June 7, before its blackout period began.

- June 7: The May jobs report showed nonfarm payrolls rose 75,000, missing all estimates in a Bloomberg survey, with the unemployment rate steady at 3.6%.

- June 7: Trump tweeted that tariffs on Mexican goods, which sparked a massive flight-to-quality trade in Treasuries, were “indefinitely suspended.”

- June 12: Consumer price index data missed estimates.

- June 14: Retail sales were stronger than expected, while the University of Michigan's gauge of expected inflation fell to an unprecedented low.

- June 17: The New York Fed’s Empire State Manufacturing Index plunged in June by the most on record.

- June 18: European Central Bank President Mario Draghi promised that officials are ready with stimulus if needed.

- June 18: The S&P 500 came within 0.8% of a record high.

This is a decidedly mixed bag. The labor market remains strong but is slowing from its breakneck pace. Inflation is at risk of persistently undershooting the Fed’s target. Business confidence is weakening, though consumers are resilient. And central banks around the globe are shifting to easier policy in anticipation of slower growth ahead. The Fed’s own updated projections reflect this murky outlook: Growth is now seen as higher in 2020, at 2%, while officials predict inflation will be lower than they thought in the coming year and a half.

Powell took the path of least resistance. Just as the first rule of bond trading is “don’t fight the Fed,” one mantra of heading up the central bank could well be summarized as “don’t fight the markets.” He made abundantly clear that officials have had a “significant” change in their outlook relative to earlier this year, as evidenced by the adjusted FOMC statement.

I wrote earlier this week that this Fed decision would show if the markets broke Powell. It’s possible that already happened in late December, when stocks were in freefall and Trump privately discussed firing his pick to lead the central bank. In what’s known as the “Powell pivot,” in early January he backed off from his previously firm stance that the balance-sheet runoff would continue on “automatic pilot” and went from shrugging off “a little bit of volatility” to assuring investors that he was attuned to the market’s concerns about downside risks.

Bond traders, meanwhile, can quickly move on from debating whether the Fed will lower interest rates this year to when those cuts will begin. Policy makers left themselves some room to maneuver, but not much. In fact, the updated 2019 dot was close to forecasting an interest-rate reduction. After capitulating to markets this time, it would seem as if July is definitely in play. Fed funds futures indicate a cut next month is a near certainty.

“They’re delivering on and above market expectations,” Jeffrey Rosenberg, systematic fixed-income senior portfolio manager at BlackRock Inc., said on Bloomberg TV. “The markets will now expect action in July,” added Michael Gapen at Barclays Plc.

It’s regrettable that Powell didn’t show more backbone. Sure, his overarching goal is to sustain the economic expansion, and it’s clear that the data isn’t as strong as it was during the zenith of the tightening cycle. But that’s to be expected at this point, a decade after the recession ended and amid some self-inflicted pain on the trade front.

This is a crucial time for the Fed and for monetary policy in general. Given that the ECB and Bank of Japan haven’t managed to wean their economies off extraordinary stimulus measures, it raises tough questions about whether central banks are doing more harm than good with what appears to be a tendency to prop up markets at every turn. Powell did a better job than his predecessor at staying the course, but he has proved willing to capitulate at most turns in 2019.

Powell has advantages that his counterparts don’t, including a stronger domestic economy and a policy rate that has increased eight times since December 2016. He at least has a bit of room to try an “insurance cut” to keep the good times going.

But fractionally lower interest rates aren’t going to magically fix the U.S.-China trade tensions nor provide the spark needed to lift inflation or encourage vast business investment. It serves mostly as a signal to Wall Street that the Fed knows its cues. Powell can only hope that the short-term high will be worth it in the long run.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.