Bond Traders Outsmart the Fed and Themselves

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Every once in a while, bond traders get too clever for their own good when it comes to handicapping the Federal Reserve. They’ve been mostly spot-on over the past two years, with their last blunder coming in early 2017, when they failed to anticipate the central bank’s resolve to boost interest rates in March.

Based on recent market moves, it’s starting to feel as if they’re out of control again.

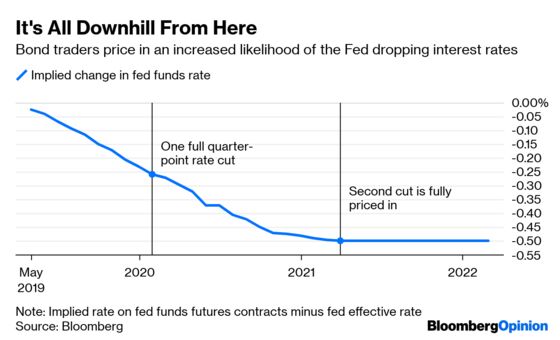

Fed funds futures indicate traders are betting on almost a full quarter-point rate cut by the end of this year, and eurodollar futures show roughly the same odds. That’s even as the S&P 500 hovers near a record high, the yield curve that the Fed watches for signs of recession is no longer inverted, and the U.S. unemployment rate is close to a 50-year low. To top it off, Commerce Department data Friday showed the American economy grew at a 3.2 percent annualized pace in the first quarter, topping all forecasts in a Bloomberg survey.

So, what’s got bond traders so convinced a cut is coming? A rush of demand for dovish hedges earlier this week seemed to follow a Wall Street Journal article titled “Fed Officials Contemplate Thresholds for Rate Cuts.” It strung together recent comments from policy makers about whether inflation running below their 2 percent target for a prolonged period would justify lowering interest rates. It added that Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida pointed out that the central bank “took out some insurance cuts” in the 1990s even though the U.S. wasn’t staring down a recession. Bloomberg News’s Vivien Lou Chen explored the similarities between then and now:

The global economic backdrop was darker back then, given the Asian financial crisis, Russia’s debt default and the near-collapse of hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management. But other aspects of 1998 seem eerily similar to today, say Tilley and BMO’s Jon Hill. The U.S. economy was humming along, inflation was low, and the S&P 500 Index was at or near a record. When the Fed cut rates that year, it kept the longest postwar U.S. expansion going.

“You have to pay respect to what the market is pricing in,” said Brett Wander, who oversees $28.7 billion as chief investment officer for fixed income at Charles Schwab Investment Management. “A rate cut is a scenario that people have got to consider, even if it’s not the most likely scenario.”

Sure, it’s the job of investors to watch market pricing, but Fed Chairman Jerome Powell probably doesn’t care about respecting the implied odds of a cut from eurodollar futures. He already had to capitulate so much earlier this year, both by throwing in the towel on further gradual interest-rate increases and by ending the central bank’s balance-sheet runoff earlier than he most likely wanted. The U.S. economy, as he likes to say, is in a good place. The Fed can afford to sit back and let things play out without rocking the boat with a jolt of monetary easing. Officials should make that clear in the Federal Open Market Committee’s May 1 decision.

An interest-rate cut could very well do more harm than good for investor sentiment. Suppose the Fed decides that the current fed funds target range of 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent is actually restrictive and that policy makers ought to drop the benchmark accordingly. Those rates are already far lower than where the central bank ended past cycles. When the Fed began hiking in December 2015, policy makers expected the neutral rate would be 3.5 percent. For a while, every extra rate boost seemed like a struggle — those like Powell who have been through them all should be reluctant to give back those hard-earned increases.

The political optics, of course, further complicate the calculus. White House National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow has said in multiple interviews that the fed funds rate should be lower (but of course noting that he respects the central bank’s independence). President Donald Trump has been even more critical:

As much as Fed officials try to stay out of the political arena, they are undoubtedly aware that cutting rates would look like they’re caving to this one-sided scrutiny. The world’s most powerful central banks often speak as one, which is notable given that European Central Bank President Mario Draghi said earlier this month that he was “certainly worried about central bank independence,” and especially “in the most important jurisdiction in the world.” He’s more free to say what Fed policy makers are thinking.

Even if the Senate confirms conservative economist Stephen Moore, Trump’s recent Fed pick whose views on monetary policy appear to shift depending on which party controls the White House, the central bank won’t suddenly bend to political pressure. As former New York Fed President Bill Dudley wrote for Bloomberg Opinion earlier this week, the leadership troika of Powell, Clarida and John Williams will keep policy on a steady course. Dudley also agrees that the Fed is far from cutting interest rates.

That said, traders have to trade, and even if they’re of the mind that the Fed will stand pat, they need to hedge against the unexpected. Right now, nothing seems to be pointing to further interest-rate increases, while there are at least a few reasons to think a cut could be in the cards. The most recent signs of slowing global growth came from Asia: In South Korea, a bellwether for global trade and technology, the economy shrank by 0.3 percent, the most in a decade. The Bank of Japan soon afterward warned of “high uncertainties” in its growth outlook. And, crucially, Fed officials seem as perplexed as ever that inflation isn’t rising toward their target level. Friday’s data on quarterly price changes cemented those concerns.

Traders can always find reasons to talk themselves into buying protection from Fed rate cuts. That doesn’t mean it deserves to morph into the driving narrative in the world’s biggest bond market. Barring another big dive in the stock market or some truly harrowing U.S. economic data, Powell and his colleagues would be wise to step aside. For all they know, the fabled soft landing might very well be unfolding.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.