A New Energy Paradigm Must Confront the Old

BloombergNEF’s new report on the future of electricity shows how coal and gas block the path to progress.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Nothing blocks a pathway quite like a giant power plant. Or a coal mine. Or a gas field.

Two tomes released in the past week, one looking back and the other ahead, show the enduring importance of facts on the ground (or under it) when it comes to the transition toward lower-carbon energy. BP Plc’s latest Statistical Review of World Energy set the tone with its headline, “An unsustainable path”. The report showed carbon emissions rose at their fastest pace last year since 2011, hitting a new record. Worse, this came on the back of unexpectedly strong growth in primary energy demand, much of which BP attributed to weather effects – people turning on air conditioners in unusual heat or heating in bitter cold, hinting at pernicious feedback loops generated by climate change.

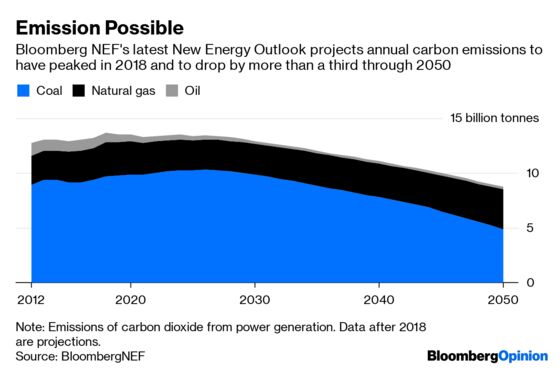

On Tuesday, BloombergNEF released its latest New Energy Outlook, forecasting the shape of the global electricity sector out to 2050. In certain respects, this sounds a more optimistic note, describing a scenario whereby power generated without fossil fuels rises to about 70% of the global mix from just over a third today. Wind and solar power become the biggest sources, together comprising around half the mix. Last year, BloombergNEF expected power-sector emissions to peak in 2027; now it estimates they peaked last year and should fall 36% by 2050.

Yet even this isn’t necessarily compatible with limiting the average global temperature rise to less than 2 degrees Celsius (3.8 Fahrenheit), let alone the 1.5 degrees-level that could make a big difference in mitigating potentially catastrophic effects. As BloombergNEF’s analysts write:

The outlook for global emissions and keeping temperature increases to 2 degrees or less is mixed, according to this year’s NEO. On the one hand, the build-out of solar, wind and batteries will put the world on a path that is compatible with these objectives at least until 2030. On the other hand, a lot more will need to be done beyond that date to keep the world on that 2 degree path.

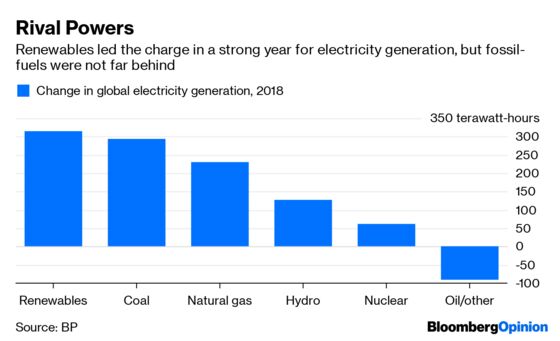

Part of the problem is sheer incumbency. Reviewing 2018, BP found renewable energy led the growth in global power generation. Yet coal came in at a close second, and fossil fuels overall accounted for almost half the growth.

Some of that increase in coal-fired power was cyclical. But it also reflects the simple fact that once a power plant – or any other manufacturing facility – has been built, owners want to keep them running as much as possible, and changing that requires a big shift in economics or policy. Capacity utilization for China’s coal fleet jumped back above 50% last year for the first time since 2014, according to BloombergNEF’s data, and the entire fleet has expanded by 39% in that period. As Gregor Macdonald, author of “Oil Fall”, tweeted after BP’s report was published: “although wind+solar move fast, they need to move even faster to smother marginal growth from [fossil fuels]”.

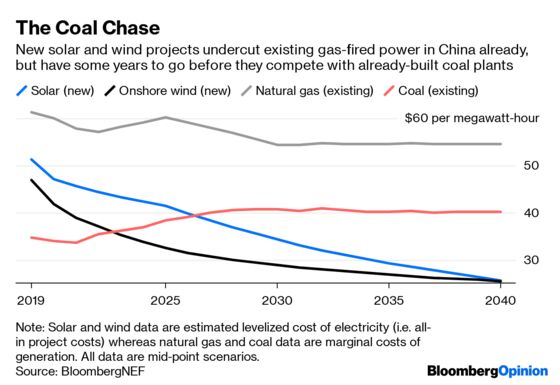

The great advantage of wind and solar power is that they are manufactured types of energy, rather than extracted forms such as coal. Hence, their cost has fallen rapidly and should continue doing so. BloombergNEF calculates the all-in costs of electricity from wind and utility-scale solar power have dropped by 49% and 85%, respectively, since 2010. They’re now cheaper than power from a new coal or gas-fired plant across two-thirds of the world, up from less than 1% only five years ago, and that includes China.

However, existing coal or gas-fired plants are a different story; they get switched on provided they can cover just their running costs. For example, BloombergNEF doesn’t expect solar power to undercut existing coal plants in China before 2027.

This isn’t just an issue in China. New solar projects in India don’t undercut existing coal-fired generation economics until 2039, under BloombergNEF’s projections – and not until 2049 under its low-price scenario.

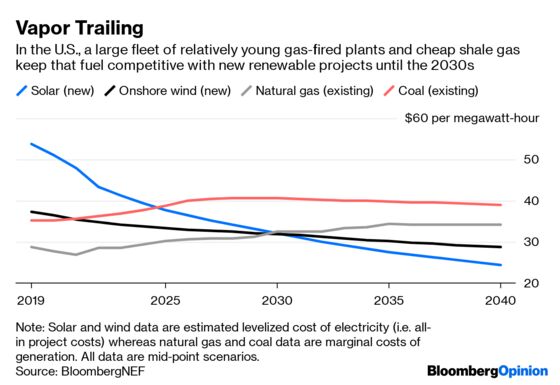

Nor is this confined merely to Asia’s powerhouses. The White House’s black-lungs-matter campaign may not be making much headway, given coal-fired plants are expected in 2020 to burn roughly half the amount they did in 2010, according to government projections. Natural gas from fracking is a different story. Last year’s surge in U.S. production was the biggest for any country ever, according to BP; producers in the Permian basin flare (burn off) more excess gas every day than is used by the entire residential market in Texas. Hence, despite U.S. gas demand having risen by almost a third over the past decade, prices have crashed. In America, the stubborn incumbent against which renewables must compete is invisible.

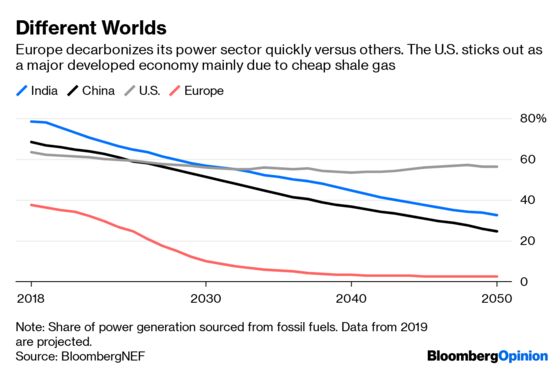

Little wonder, then, that fossil fuels keep a grip on the power sectors of China, India and the U.S.; while Europe – without either a fleet of new coal plants or access to cheap gas – decarbonizes much more, in BloombergNEF’s view:

Shale gas has played a central role in cutting U.S. carbon emissions thus far by helping to displace coal-fired power. Ultimately, however, it will also block progress toward a sub-2 degrees scenario for limiting climate change, unless zero-emission forms of energy can somehow out-compete it. That’s especially so when considering adjacent aspects of decarbonization, such as electrifying transportation and heating.

It’s possible the costs of renewable energy, and batteries, fall even faster than BloombergNEF anticipates, or that other technologies such as carbon-capture eventually prove useful and cost-competitive at scale. Then again, maybe not.

What BloombergNEF’s report shows is that, under reasonable assumptions built around existing technologies and market design, the global power sector can get us so far along the path to limiting climate change but not the whole way. Unblocking that way requires further redesign of our energy markets, most obviously by pricing the outcome we want – fewer emissions – via carbon taxes or something similar.

Here, however, the blockage is less economic and largely political. China’s role in financing new coal-fired power plants across Asia is one big challenge. Meanwhile, in the U.S., the most interesting recent development on this front is moves by some Congressional Republicans to recast themselves as concerned about climate change but oddly in favor of picking winners among technologies – nuclear power and carbon-capture, especially – and spouting buzzwords like “innovation” rather than putting a price on carbon and letting capitalism do its thing.

That they feel the need to move at all is telling, however, and points to a risk embedded within BloombergNEF’s analysis and the unsustainability mentioned in the title of BP’s report. Given the scale of the changes required to our energy systems and the incumbent power of fossil fuels, relying on technology to simply solve it all, in the absence of market reforms to encourage that, is magical thinking.

And as the clock ticks, and political fortunes swing this way and that, the moment for market-based measures to clear out the old could well give way to something more drastic.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.