Illiquidity Threatens an Early Winter for Funds

For regulators, worrying about vanishing liquidity is one thing; doing something about it is quite another.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Bank of England and Financial Conduct Authority have stepped up their rhetoric about the dangers posed by funds offering customers daily redemption rights while investing in stuff that may prove hard to sell when times get tough.

The problem they and their fellow regulators face is that market liquidity is an elusive, contradictory thing: It can be reliably ever-present when it isn’t needed – only to vanish as soon as it’s desperately desired.

Bank of England Governor Mark Carney is unequivocal in his condemnation of the status quo. “These funds are built on a lie, which is that you can have daily liquidity for assets that fundamentally aren’t liquid,” he told U.K. lawmakers last month.

His ire stems, in part, from local embarrassment. The three most recent high-profile liquidity lapses – GAM Holding AG’s Tim Haywood, Neil Woodford, and H2O Fund Management’s Bruno Crastes – involved investors operating out of the U.K.

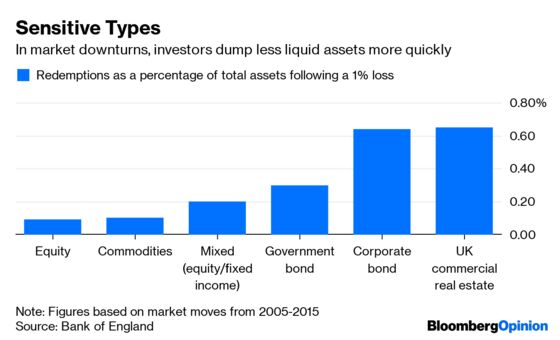

The central bank’s Financial Stability Report, published last week, makes it clear that the corporate bond market is where regulators see the biggest risk of investors being trapped in an illiquid asset class as everyone flees for the exit at once.

The Bank of England estimates that total assets managed by open-ended funds have more than doubled since the global financial crisis to about $55 trillion today. Some $30 trillion of global funds “offer short-term redemptions while investing in longer-dated and potentially illiquid assets, such as corporate bonds,” the report says.

Those funds have become an increasingly important source of buying for sterling-denominated corporate bonds, accounting for 13% of ownership last year from about 8% in 2006.

And, in an echo of the credit deterioration seen across the world in corporate borrowing, the U.K. market has become dominated by low-rated, riskier assets. By the middle of this year, the Bank of England estimates that the share of sterling corporate debt with the lowest BBB investment-grade rating had surged to 47%, up from just 16% in 2008.

When it introduced new rules governing price disclosure last year, the European Securities and Markets Authority calculated that just 220 of the 71,000 bonds it assessed across the European Union traded frequently enough to qualify for real-time reporting. In February, ESMA said 429 bonds met the criteria – still a tiny fraction of the corporate bond universe.

With 470 billion euros ($528 billion) of European corporate and bank debt now yielding less than zero, the scope for a swift deterioration in prices is clear. No wonder the market overseers are worried about a rush for the exit in the event of a market accident.

But if the risk of liquidity drying up is relatively easy to explain, the likely solutions aren’t particularly palatable or practical.

One of the issues facing a fund that gets into trouble is the first-mover advantage that accrues to investors who get out earliest.

“When fund managers sell assets, they should sell a representative slice of the fund, and not the more liquid assets first, to ensure remaining investors are treated fairly,” according to last week’s Financial Stability Report. In practice, that would be very hard to achieve.

A paper published by the Financial Conduct Authority in May studied so-called swing or dual pricing, a practice designed to eliminate that first-mover advantage by passing on transaction costs to exiting investors.

“Our analysis also documents a cost associated with alternative pricing rules: Funds with alternative pricing rules have difficulty attracting new investor capital outside the crisis periods,” the paper concluded.

One solution might be to change the rules so that funds don’t have to let investors get their money back on a daily basis. But that’s also tricky.

“It’s not clear how strong consumer demand for absolute daily liquidity is,” Bank of England Deputy Governor Jon Cunliffe said last week. “But if everyone else in the market is offering it, it’s difficult for one fund not to offer it.”

Last week’s stability report said the U.K. central bank and the FCA will study the pros and cons of a closer match between how quickly investors are allowed to withdraw their cash with how long it would take to sell a fund’s assets. But it acknowledged how difficult it will be to secure international agreement for any shift in the rules. If British regulators can’t get that, there’s a risk that the country’s fund management industry could be put at a competitive disadvantage.

“Is my fund a liquidity trap?” Morningstar asked visitors to its website this week. The best answer currently available to that question is probably “no, it isn’t – until it is.” Let’s hope no more funds blow up or get gated while regulators grapple with what may well turn out to be an intractable dilemma.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.