When the End of the Earth Isn’t Far Enough to Escape the World

Australia and New Zealand thought they were immune from everywhere else’s economic ills. Monetary policy suggests otherwise.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The term “Down Under” as a somehow blessed space separate from the realities of the rest of the world really ought to be banished, at least from discussions about economics.

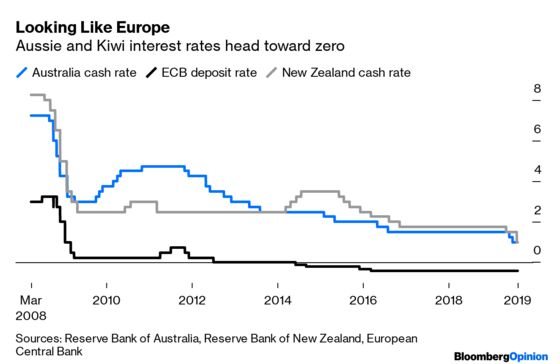

The direction of monetary policy in Australia and New Zealand is headed upside down after years of exceptionalism. As four central banks across Asia reduced interest rates last week, three of them surprises, the key development was the foreshadowing of so-called unconventional measures by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and, two days later, its sibling, the Reserve Bank of Australia. It makes sense to prepare the ground for what was considered radical pre-2008 but is now utterly mainstream in developed nations.

To appreciate the full import of what is happening, a little psychological journey is required. For years, Australia and New Zealand thought themselves special, possessed of a magic formula to escape the ills of the northern hemisphere. The gushes from Federal Reserve folks about the marvel of Australia's 27 years without a recession fueled such belief. Throw in the Sydney Olympics and Tom Cruise sightings (during the Nicole Kidman era) and it all became a bit much. I’ve lived outside Australia for almost a quarter century and recall being struck by a creeping hubris on my visits home.

For their part, Kiwis love to trumpet how they pioneered inflation targeting and renovated a heavily protected economy in the 1980s, setting them up for happy days. When overseas tycoons began snapping up remote property to prepare for vague societal breakdown in the West, some took pride in being at the end of the earth. The spike in property prices grew so bad, though, that the government restricted land sales to foreigners.

There's something to all the plaudits. Growth, whatever its crests and valleys, is better than recession. And I have never heard RBA Governor Philip Lowe, whose term began three years ago, sound anything other than prudent and insightful. RBNZ chief Adrian Orr, fairly new to the job, gets credit for not dismissing extra steps in announcing the dramatic half-a-percentage-point clip in the main interest rate.

But don't let their leadership qualities obscure the broad point: When it comes to something as vital as the price of money, Australia and New Zealand aren't so different from everywhere else. Lenders pay borrowers for the privilege of extending them cash in the euro zone, Switzerland, Japan and the Nordic area. Quantitative easing remains in Japan and existed in euroland until recently; it may well be introduced there again. Massive bond buying was famously deployed during and after the financial crisis by the Federal Reserve.

Antipodean officials would be remiss not to game it out. What was once dismissed as a kind of policy pollution from far away is now plausible and requires consideration, thanks to diminishing business confidence, induced in large part by trade wars, and anemic inflation.

Benchmark interest rates are at record lows of 1% in both countries and the central bank chiefs were pretty candid in flagging the possibility, if not yet probability, of negative rates or quantitative easing. One got the sense they were ready for the questions and opted to lean in, rather than fudge about hypotheticals.

Lowe flagged the issue before a parliamentary committee, acknowledging an underlying shift in the global landscape. Rates would be lower for longer and that might not be the end of it. Under questioning from Labor legislator Andrew Leigh, Lowe reviewed circumstances in Switzerland, Europe and Japan and what lessons might be learned for Australia.

It was a revealing exchange. Negative rates, as the three jurisdictions have, aren’t the only route. Lowe was at pains to stress that the RBA getting to zero, while possible, isn't yet his base case. More explicit forward guidance than the soft variety now used in Sydney is one option. Very clear and consistent communication is paramount.

As if to punctuate that idea, he continued: “We're not doing this because we think it's likely; we're doing it because it's prudent in the global circumstances we face.''

Quite. Forty-eight hours earlier, Orr told reporters that it was “easily within the realms of possibility that we might have to use negative interest rates’’ or other non-standard measures. He said he's hoping that the relatively aggressive cut on Aug. 7 would do the trick.

Hope is fine, preparation better. Even if the result isn’t exactly 100% pure, as a popular, though tired, New Zealand tourism slogan would have it. Might be an idea to put a moratorium on that as well.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Patrick McDowell at pmcdowell10@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.