The Amtrak That Works, and the Amtrak That Doesn’t

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- By the time it crossed the Mississippi River at Burlington, Iowa, last week, our California Zephyr was running more than eight hours late on its journey from the San Francisco Bay Area to Chicago. The last meal, a free, off-menu beef stew, had just been served in the dining car. My wife and I opted instead to consume a couple of Maruchan Instant Lunch cups, purchased in the cafe, accompanied by a half bottle of Kendall-Jackson chardonnay, also from the cafe. Occasional wafts of sewage odor tainted the air, the aging Superliner cars creaked and rattled, and the dining- and sleeping-car staff exuded fatigue and resignation. Even the conductor, who had just gotten on at Ottumwa, sounded appropriately defeated when he reaffirmed over the loudspeaker that, yes, every connecting train in Chicago, including the Lakeshore Limited to New York for which we had tickets, would be leaving before our train got there.

Things did improve a little once we entered Illinois. My wife got an unexpected email from Amtrak with a PDF ticket attached for the next day’s Lakeshore Limited, in more spacious accommodations than what we had originally booked. The train also started going consistently faster, mostly between 70 and 80 miles an hour, chipping away at our estimated arrival time by a minute here and a minute there until we were forced to sit still outside the Chicago suburb of Naperville to let a Metra commuter train go by. After a lovely day in Chicago (we stayed with friends, but Amtrak would have put us up in a hotel if needed), we boarded the train to New York only to learn that its departure would be delayed two hours to wait on two very late trains arriving via different routes from Los Angeles, the Southwest Chief and Texas Eagle. The conductor sounded irked about this rather than resigned, and over the next 20 hours we made up about a third of the lost time, arriving in Manhattan in the middle of a minor blackout that spared Penn Station but made getting home from there something of an adventure. Isn’t long-distance train travel great!?!

Actually, it is. I’m not hankering to get on the California Zephyr again anytime soon, but I’m glad to have had the experience. It offered spectacular scenery, mealtime encounters with interesting people from all over (if you’re in a party of less than four, you’re always seated with strangers), and hour after hour after hour of mostly blissful reading and napping. A few months ago, the New York Times Magazine had a detailed account by journalist/humorist Caity Weaver of a trip from New York to Los Angeles on the Lakeshore Limited and Southwest Chief that captured the vibe quite nicely, so I’ll stop here with the travelogue and start with some numbers.

Yes, that’s right: The California Zephyr, with one eastbound train a day and one westbound, lost more money last year than any other service operated by the National Railroad Passenger Corp., aka Amtrak. On a per-passenger-mile basis, it wasn’t so bad (the three-times-a-week Sunset Limited was the worst), but still, the operating losses from the California Zephyr, Southwest Chief and Empire Builder together nearly equaled Amtrak’s total fiscal 2018 operating loss of $170.6 million. Since the start of fiscal 2019 in October, the California Zephyr alone has lost $40.9 million, even as Amtrak’s operating loss has dwindled to $50.9 million and is projected to approach zero for the full fiscal year.

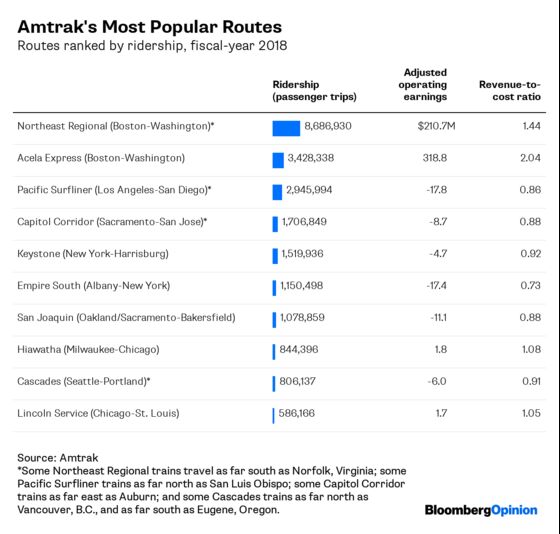

This is possible because Amtrak also operates on shorter routes with much more frequent services that carry many more passengers and in some cases even turn big operating profits:

These numbers include subsidies from the states, which add up to about 7% of overall operating revenue, with California and Illinois the biggest contributors. They leave out capital expenditures, which are highest for the Northeast Corridor along which the Acela and Northeast Regional trains travel because Amtrak owns most of the track and is thus responsible for its upkeep. The California Zephyr uses track owned and maintained by freight railroads BNSF, a subsidiary of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., and Union Pacific Corp. But that’s actually a big part of the problem faced by it and other long-distance routes.

The 1970 federal law that released private railroads from the obligation to carry passengers and created Amtrak decreed that its trains be given priority over freight. But because Amtrak’s long-distance trains run infrequently on tracks controlled by others and a certain amount of schedule unpredictability is inherent in the distances they travel — and because, Amtrak complains, the freight railroads aren’t obeying the law — they are constantly being delayed by conditions outside their control.

The California Zephyr that I traveled on started out about an hour late because of engine problems, kept getting later because of congestion and track work, had to restrict its speed while climbing the Rockies in Colorado because it was hot out, took a seeming eternity to back into and then pull out of Denver’s Union Station, endured more track-repair-related slowdowns amid the waterlogged cornfields of Nebraska, then came to a halt because the conductors and engineer had been on the job for 12 hours straight and another federal law required that they sit tight until a replacement crew came in from Lincoln. On the westward journey two weeks earlier, my wife and son (he and I each flew one way) spent several early-morning hours parked near the Nevada-Utah border after their train pulled onto a siding to let a faster-moving freight train pass, and the freight engine promptly broke down.

On track that Amtrak owns or otherwise exercises some control over — or even just uses frequently enough that its comings and goings can be counted upon — these problems are less pronounced. Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor trains were on time at 76.2% of their stops in fiscal 2018 and its other short-haul trains 77.7%. For the long-distance trains, that percentage was only 52.1%, even though they’re subjected to a looser definition of “on time” than shorter routes are.

Amtrak, then, is really running two train systems. One provides residents of cities in the Northeast, Midwest and along the West Coast with regional train service that’s not great by Western European or East Asian standards but is useful to lots of people and seems like it could get by on ticket revenue, state subsidies, and some federal help with financing big capital projects such as that much-needed new tunnel under the Hudson River. The other consists of 15 longer routes that have appeal for tourists, residents of some isolated towns and airplane-shunning Amish folk (if riding Amtrak through the Midwest was your only experience of this country, you’d think it was about 10% Amish) but cannot survive without ongoing operating subsidies from Congress. The $1.9 billion that Congress appropriated to Amtrak for fiscal 2019 amounts to only about 0.04% of total federal spending, and one could perhaps argue that subsidies for long-distance rail are worth it in some kind of nation-building or nation-advertising sense. But those subsidies do seem to reduce Washington’s appetite for investments to upgrade Amtrak’s more heavily traveled intercity offerings, which are of far more economic value.

Current Amtrak Chief Executive Officer Richard Anderson, who once held the same job at Delta Air Lines Inc., has considered this situation and, as the Wall Street Journal’s Ted Mann described a few weeks ago, understandably concluded that the long-distance routes aren’t a priority. Last year, for example, Anderson said that rather than pay to maintain a 219-mile stretch of Southwest Chief track that owner BNSF no longer uses, Amtrak would replace the train with bus service between Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Dodge City, Kansas.

The White House has taken a similar stance, arguing in the proposed fiscal-year 2020 budget that:

The Long Distance network has not changed from its original iteration 40 years ago. It does not provide efficient services in areas where passenger rail is a competitive form of transportation and inadequately serves low population areas through which they [sic] travel with infrequent and inconvenient service. The Budget proposes that Federal operating support for Long Distance routes would now be provided through the Restoration and Enhancement (R&E) Grant program, not Amtrak's annual grant, and then phased out entirely.

Senators from the affected states forced Anderson to back down on his Southwest Chief plan, though, at least through this fiscal year. And President Donald Trump — who seems at best only faintly aware of the things that Office of Management and Budget Director (and acting chief of staff) Mick Mulvaney puts in the annual budget proposals — surely isn’t going to make cutting rural train service a priority in the run-up to the 2020 election, and wouldn’t make any headway on Capitol Hill even if he did. If I’ve read the maps correctly, the 10 money-losing long-distance trains in the table above travel through 36 states, while the 10 most popular routes touch just 14. Amtrak definitely has a future, with ridership up 41% since 2000. But the arithmetic of U.S. Senate representation and Electoral College votes may keep it chained to its past for a while yet.

Trips of up to 250 miles are considered on time if they arrive less than 10 minutes beyond the scheduled arrival time; 251-350 miles, 15 minutes; 351-450 miles, 20 minutes; 451-550 miles, 25 minutes; and greater than 550 miles, 30 minutes.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.