Another Emerging-Market Crisis May Be Brewing in Asia

India’s economy is probably growing slower than the 7% claimed in official statistics, but its arch rival is faring a lot worse.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Pakistan is flirting with a textbook emerging-market crisis. An unsustainable investment boom has ended. The central bank has raised interest rates to squeeze a current account gap. Growth has collapsed to a nine-year low; youth unemployment is in double digits; and inflation is getting there. Government revenues are stalling.

Getting Islamabad out of its jam is once again the job of the International Monetary Fund. The IMF has put together the country’s 13th bailout since the late 1980s, but it doesn’t want its $6 billion of rescue funds to be used to pay Chinese loans for Belt and Road projects. The fund’s suggestion to let the currency float freely could extend its 30% decline against the dollar since December 2017.

Throw in fiscal austerity, which had an unmistakable imprint on the government’s budget on Tuesday, and the pain’s bound to get worse before it gets better. Rather than having to deal with stagflation and balance-of-payment deficits, Prime Minister Imran Khan is probably wishing he was in England at the Cricket World Cup, which Pakistan won for the first and only time under his captaincy in 1992.

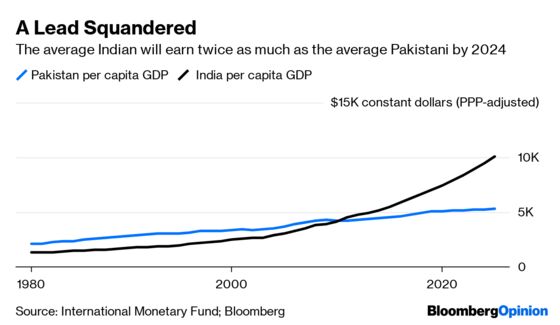

At that time, Pakistan’s per capita real GDP, adjusted for purchasing power of the currency, was 65% higher than India’s. Now it’s 28% lower than its neighbor’s level, and the IMF expects the gap to keep widening.

India’s economy is probably growing much more slowly than the 7% rate claimed in official statistics, but its arch rival is faring a lot worse. The construction frenzy sparked by the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor has petered out. Three cement makers are among the biggest losers on the Karachi Stock Exchange’s KSE100 Index this year, with price drops ranging between 45% and 55%. Even the worst performer on the index – Fauji Foods Ltd. – can chalk up the collapse in its shares to the souring of a deal with Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group Co. The Chinese firm was supposed to buy 51% of the Pakistani dairy company.

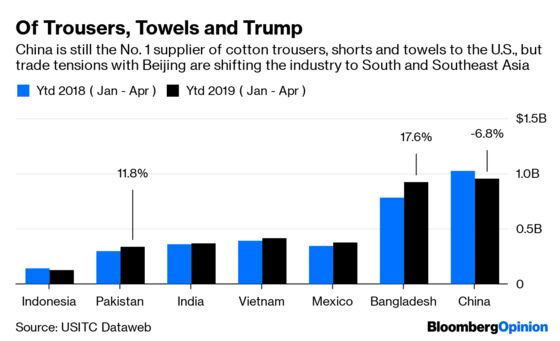

So how will the IMF turn Pakistan around? For an answer, try cotton terry towels, trousers and shorts. As U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade war against Beijing intensifies, American buyers are diversifying their supplier base away from China, the No. 1 exporter of these goods to the U.S. Already, Bangladesh is close to snatching the trousers-to-towel crown. Pakistan, at No. 6 last year, has grown its own shipments to the U.S. by almost 12% this year. It may overtake India, which has seen virtually no improvement.

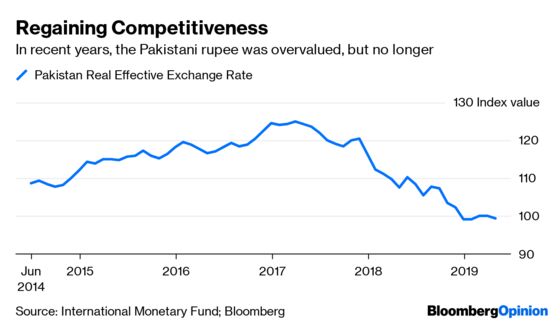

The good news is that the Pakistani rupee has fallen by almost 20% since 2017. That’s virtually wiped out the currency’s overvaluation adjusted for inflation differences with trading partners, as estimated by the IMF. If the currency slides further and inflation doesn’t accelerate, Pakistani exports should receive a boost, provided global growth and cotton availability for the textile industry hold up.

Auto sales shrank 24% from a year earlier in April. With two-fifths of sales financed by loans, only a meaningful reduction in interest rates can spur demand, especially with carmakers passing on the bulk of the burden of a weak exchange rate (on import costs) to consumers. Only two analysts out of 14 tracked by Bloomberg rate the shares of Pak Suzuki Motor Co. a buy. Subsidized interest rates on low-cost housing could plug the demand shortfall to some extent. But the fiscal elbow room to run such ambitious programs is too limited. Besides, boosting agricultural yields may be a bigger priority than supporting urban consumers.

Khan’s administration was hesitant to tap the IMF, knowing how tough it is to persuade the public of hardships that must be endured as the economy is wrung dry of past excesses. Structural adjustments could also have political costs. Khan, who took charge nine months ago, is the nation’s 19th elected prime minister. None of the 18 before him managed to complete their five-year term.

Now he has no choice but to embrace the conditions that come with the rescue. The prime minister can only hope that the reordering of global supply chains will create opportunities and ease the pain of Pakistan’s recovery. A world cup win would also lift sentiment, but the odds on that are rather long.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services. He previously was a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He has also worked for the Straits Times, ET NOW and Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.