(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Whatever you were hoping to see in this week's buffet of industrial-linked economic data, you probably got it. U.S. orders for non-military capital goods excluding aircraft fell 0.1 percent in February, which marks the third drop in four months. But the Institute for Supply Management’s gauge of U.S. factories climbed more than economists expected in March, with nearly all industries showing growth. While the U.S. as a whole added more jobs than expected in March, the manufacturing sector – which had been losing hiring momentum in recent months – posted an outright decline of 6,000 jobs. That’s the biggest drop since August 2016, when the industrial sector was coming out of a mini-recession prompted by slumping oil and commodity prices. On the other side of the world, a manufacturing benchmark in China pushed into expansion territory in March. Some took it as a sign of a rebound or at least stabilization, while others pointed out seasonal volatility and noted that the improvement in the gauge wasn’t that big on a historical basis. Meanwhile, in Europe, Germany’s economy is now expected to grow in 2019 at the weakest pace in six years. The country’s Economy Ministry flagged “a lack of external demand” as factories posted yet another month of slumping orders in February.

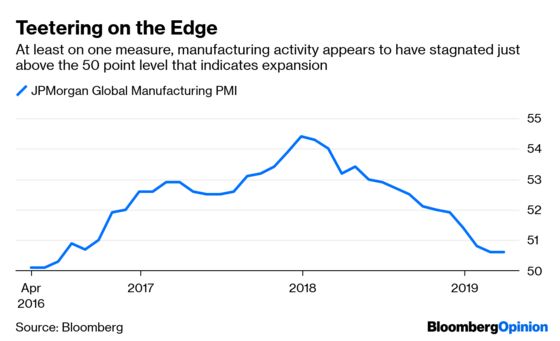

If your head is spinning, you are reading it right. I tend to interpret this data smorgasbord as fits and starts on the way to a slowdown. It seems too optimistic to think that China or the U.S. can isolate themselves from the gloom emanating out of Europe for long, especially as the various trade battles take a toll on demand and businesses’ willingness to invest. In comments last week, China’s Premier Li Keqiang said the country’s domestic economy was improving, but warned of mounting uncertainties globally that had impacted market confidence. And while reports that China and the U.S. are nearing some sort of agreement on trade has given some investors grounds for optimism, the two sides are still at odds over enforcement mechanisms, intellectual property protection and the rollback of tariffs. Call me a cynic, but if those important issues are still outstanding, I’m not sure how “close” a deal really is. The damage may already be done to this later-cycle economy. Global new export orders for the manufacturing industry slumped in March to the lowest level in nearly three years, according to the JPMorgan Global Manufacturing Index. Overall activity has stagnated at the slowest pace since June 2016. This chart seems telling:

Earnings estimates and stock prices seem to be treating slowdown worries as a blip, with investors betting industrial companies will have an ugly first quarter before a recovery in the back half of the year. The S&P 500 Industrials Sector is up 20 percent so far this year, beating the broader benchmark. FedEx Corp. is perhaps the best example of optimism gone too far, with the stock now above where it was in December when the company cut its fiscal 2019 earnings guidance amid signs the peak of economic growth had passed. Recall that FedEx cut its guidance again last month amid deteriorating conditions in Europe and Asia and an ongoing struggle to adapt to a flood of less profitable e-commerce shipments while at the same time integrating its troublesome acquisition of TNT Express NV. Given the mishmash of data, I tend to think the opinions of industrial CEOs are a more reliable predictor of economic direction, and their tone turned more cautious during the last round of earnings. The degree to which that perspective has shifted or stayed the same when the top U.S. industrial companies start reporting next week will say a lot.

BOEING’S BAD LOOK

The controversy around Boeing Co.’s 737 Max jet is going from bad to worse. The company announced late Friday that it would temporarily reduce production of the Max to 42 planes per month, down from a current pace of 52. It’s become increasingly likely that the Max’s global grounding will drag on into the summer as the Federal Aviation Administration compiles an international panel to review the aircraft and scrutiny over what Boeing did and didn’t know mounts. The company will also create a special board panel to review safety and design. Earlier this week, Boeing said it needed more time to complete a proposed fix to the anti-stall flight-control software that investigators believe was a factor in two fatal crashes of the plane in just five months. That’s a bit awkward as Boeing had hosted a junket the week before to sell the fix to pilots and journalists, and said it would have the final paperwork to the Federal Aviation Administration by March 29. Obviously, Boeing should be sure it has all the kinks worked out this time. The company reportedly discovered a problem with integrating the fix with existing flight-control infrastructure in a final audit and also unearthed an unrelated software issue. But this doesn’t inspire a lot of confidence that Boeing has learned its lesson about rushing timelines. In a preliminary report on last month’s Ethiopian Airlines crash, investigators said pilots attempted to follow the procedures to disable the flight-control system that Boeing laid out after the Lion Air crash in October. The plane still crashed, suggesting the procedure wasn’t as simple as Boeing made it seem. The findings prompted a halfway attempt at accountability from Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg. He apologized for the pain the accidents have caused, but also characterized the crashes as the result of a “chain of events” and stopped short of saying Boeing’s initial recommendations were insufficient, acknowledging only that erroneous activation of the software “can add to what is already a high workload environment.” Legal complaints are mounting, with consumer advocate Ralph Nader urging a recall of the Max on behalf of his grand-niece who died in the Ethiopian Airlines crash. That’s unlikely to go far, but Ethiopian Airlines is reconsidering an order for 25 more of the jets because of the “stigma”, following in the path of Lion Air and Indonesia’s flag carrier Garuda Indonesia.

AN ALTITUDE CHECK AT GE

General Electric Co. released a schedule on Friday of its upcoming events, and it includes an investor day at the Paris Air Show in June that will focused on its aviation unit and GECAS leasing business. GE held a similar meeting in 2015 and 2017, but this year’s event comes amid a growing debate over the value and trajectory of these crown-jewel assets. One frequent argument I hear from those advocating buying the stock is that the aviation unit alone justifies GE’s $87 billion market value, meaning investors essentially have a free option on a turnaround in the troubled power unit. That kind of valuation analysis is usually reserved for companies that are going to break up. Both CEO Larry Culp and CFO Jamie Miller have suggested recently that the health-care assets that will remain following the sale of a biopharmaceutical business to Danaher Corp. aren’t core to GE’s future and will ultimately be divested. But as far as aviation goes, it’s unclear how you disentangle that unit from the company without doing significant damage in the process. You also have to make some arguably optimistic comparisons to Boeing and Safran SA to arrive at a standalone aviation valuation in the $90 billion to $100 billion ballpark. GE predicts high-single-digit revenue growth for the aviation unit this year and free cash flow in line with the $4.2 billion it says the business generated last year, making it the only industrial division where the company isn’t forecasting a decline in cash flow. Some investors still have questions about how GE allocates its free cash flow between its businesses and want to better understand how taxes and working capital benefits from GE Capital receivables programs affect those numbers. Risks include whatever fallout may arise from the 737 Max grounding. Should Boeing decide to pursue a new middle-market aircraft, GE would need to make significant investments to win and execute on the associated engine contract. These are mostly just questions at this stage, but investors will have an opportunity to get some answers in June.

DEALS, ACTIVISTS AND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE UPDATE

Triumph Group Inc. announced this week that it’s exploring options for its aerospace-structures division, which makes aircraft wings, fuselage panels and jet-engine casing products. A divestiture would fit into Triumph’s push to rid itself of businesses that are a drag on profits and cash flow. SunTrust Banks Inc. analyst Michael Ciarmoli estimates the division could be worth $400 million to $500 million in a sale, although he says the ability to find someone to pay money for these assets would in and of itself be a win. It’s a bit surprising to see Triumph contemplating such a drastic step after spending years restructuring the business and divesting assets to reduce risk. Along those lines, Triumph also announced an agreement to transition work on wings for the G280 aircraft to Israel Aerospace Industries. The aerospace-structures unit accounts for about 60 percent of Triumph’s revenue, so the company will be significantly smaller if a sale does occur. That raises the question of whether the product-support and repair division and the integrated systems unit that makes gearboxes and control tools for landing gear could end up being takeover bait as well.

Virgin Trains USA raised $1.75 billion in the municipal bond market to fund a plan to expand its high-speed rail service along the Florida corridor. This appears to be the alternative financing option that Virgin Trains alluded to when it canceled its IPO at the last minute back in February. The shares were expected to price below the targeted range amid a lack of appetite for such a speculative bet, with the company burning through money by the trainload and running into construction delays that have caused it to miss past growth forecasts. Bond investors drooling over the high yields on Virgin Trains’ debt offering don’t seem to have the same qualms. The biggest share of Virgin Trains’ debt offering was sold for a yield of 6.5 percent(!), but the lead underwriter, Morgan Stanley, said that’s actually about a quarter percentage-point lower than what was initially offered because the sale was significantly oversubscribed. The money should help Virgin Trains add a stop in Orlando and tap into traffic to Walt Disney Co.’s resort there, a big revenue booster. But something in the 25 pages of risks in the prospectus is apt to make this investment as bumpy as Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride. Virgin Trains seems to have found the investors with the stomach for it after a relative drought of junk-rated state and local government bonds left fund managers with too much cash.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brooke Sutherland is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and industrial companies. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.