(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The year’s best-performing commodity keeps going from strength to strength.

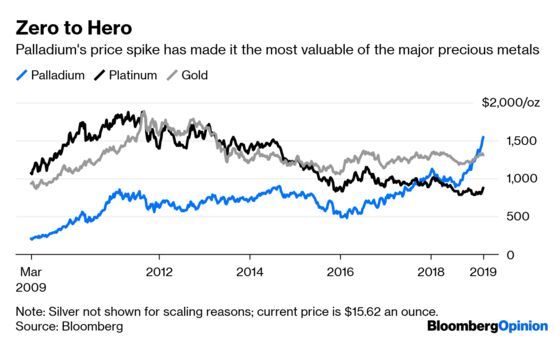

Palladium – a sister-metal to platinum that’s used mostly in car catalytic converters – has gained nearly 28 percent so far this year, outpacing the 26 percent rise in West Texas Intermediate crude, the 22 percent jump in nickel, and the 16 percent gain for lumber.

As we’ve argued, there are fundamental reasons why this performance should be robust. On the supply side, most of the world’s palladium is a by-product of southern African mines mainly focused on platinum. Their profits in recent years have been dismal, so there’s been little scope for building new projects.

On the demand side, tightening auto-emissions rules are requiring larger volumes of platinum-group metals in exhaust catalysts. Manufacturers whose converters at present use more palladium than platinum are likely to take several years to switch back to the cheaper metal.

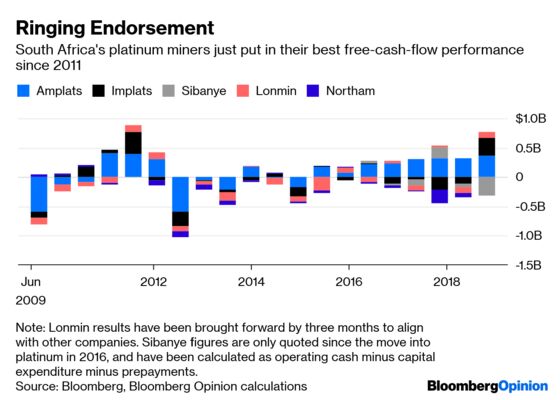

Still, if you want a glimpse of how this boom will come back down to earth, you could do worse than read through the run of financial results from South Africa’s platinum miners over the past few weeks.

For an industry that’s chalked up a collective $5.6 billion of net losses over the past five years, it’s been uncharacteristically upbeat. Both Anglo American Platinum Ltd. and Impala Platinum Holdings Ltd. posted their best half-year results since 2011, with 4.71 billion rand ($334 million) of net income at Amplats and 2.46 billion rand at Implats. Northam Platinum Ltd. still lost money at the bottom line, but its 1 billion rand operating profit was a record.

Sibanye Gold Ltd. and Lonmin Plc, which are gradually working toward an all-share merger aimed for later this year, still seem stuck in the loss-making past thanks to ongoing writedowns, strike action and a workplace death. Even there, though, things are looking up: Analysts upgraded their median forecast for Sibanye's net income in the 2020 fiscal year to $831 million from $351 million on the back of its result.

The problem with all this good news is that miners seem set on squandering their good fortune before they get a chance to enjoy it. Implats will start work on its new Waterberg project in 2021 and aims to boost output at its Mimosa joint venture by 30 percent in the meantime, Chief Executive Officer Nico Muller told Felix Njini of Bloomberg News Thursday. Amplats will increase capital spending to a range of 5.7 billion rand to 6.3 billion rand this year – up about 50 percent from two years earlier – as it seeks to boost output from its Mogalakwena and Mototolo pits.

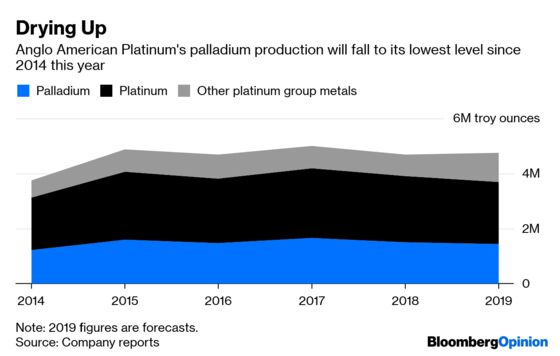

That’s not going to burst palladium’s bubble overnight. Such projects take years to get up and running. In the meantime Amplats, the biggest South African producer, is forecasting that its output of palladium will actually fall this year to its lowest annual level since 2014.

Even if other miners manage to chalk up the 300,000 troy ounce increase in supply being forecast by the biggest palladium miner MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC on Tuesday, the 500,000 ounce increase in autocatalyst demand should leave the market 800,000 ounces short in 2019.

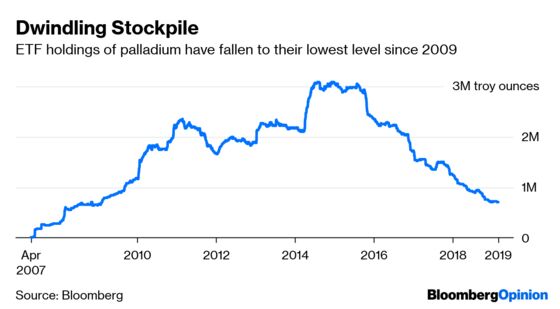

There’s no obvious way to plug that gap. One potential alternative source of new supply – holdings of palladium in exchange-traded funds – has already been whittled away by investors selling into recent strong prices. The total has now fallen to 713,633 troy ounces, its lowest level in a decade, so the market would be short even if every ounce of ETF holdings was sold.

Still, miners contemplating new palladium projects should look to the recent experience of another rare automotive metal, the cobalt used in lithium-ion batteries. Prices have slumped about two-thirds since peaking a year ago, as producers ramped up output and battery-makers sought ways to reduce their cobalt loadings.

Somewhere around the early- to mid-2020s, when new projects come on-stream, reduced-palladium catalytic converters arrive and electric cars become cost-competitive with conventional vehicles, the market for palladium could be looking similarly grim. Enjoy the good times while they last.

Russia’s palladium-rich MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC is in a different and far more profitable class, but still doesn’t produce quite as much of the element as its African rivals.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.