(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Jeff Bezos, please meet Margrethe Vestager. Ask your buddies in the technology industry. They’ll tell you that she is not a fun person to deal with.

In Brussels on Wednesday, Vestager said that European Union antitrust regulators are starting to ask questions about Amazon.com Inc.’s market power.

Clearly, she is only just starting to sniff around, and the odds are there won’t be a crackdown in Europe anytime soon, if ever. But these early inquiries should worry Bezos and his team.

First, Vestager has proved to be an aggressive foe of America’s biggest corporations, as Google, Apple Inc. and Starbucks Corp. can all attest. Amazon previously tussled with Vestager over taxes and prices in its e-book business, too.

Second, Europe’s antitrust laws differ from those in the U.S. and give Vestager a lower legal bar to clear if she finds that Amazon abuses its market power. Even if she fails to uncover any smoking guns, the EU can still dig up Amazon’s business secrets and otherwise make life painful for the company.

I was most intrigued by the fault line Vestager has zeroed in on: the company’s dual role as both a shopping mall and a shop in its own right. If — and we’re a long way from this — Vestager tries to undo Amazon’s double e-commerce model, things could get ugly for the company.

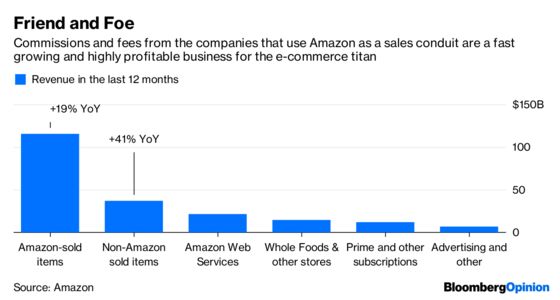

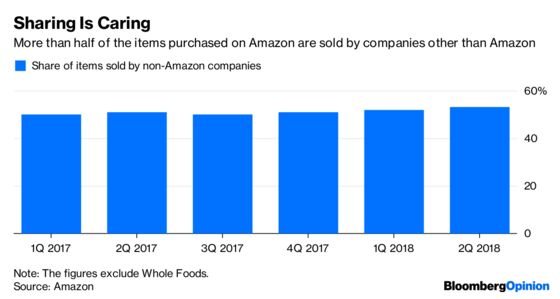

As Amazon watchers know, the company’s e-commerce operation in the U.S. and many other countries is really two businesses in one. Amazon buys KitchenAid mixers, Stephen King books and Gold Toe athletic socks from the companies that make them, and sells them to shoppers at a markup. Amazon also acts like eBay Inc. in giving other companies a shot at selling products directly to shoppers on its website. In return, they give Amazon a cut of each sale. The company says that just over half of the items purchased on Amazon come from these external vendors.

There are inherent conflicts in Amazon’s twin role as a retailer and as a conduit for other retailers. If it sells a case of Pedigree dog food, and a handful of smaller retailers sell the same product on the same platform, can Amazon really offer a level playing field? Or does it find ways to make shoppers choose the product it sells itself?

If Amazon sees that lots of its customers are buying Dawn dish soap, and then makes its own version with a similar look, and highlights that product prominently on its website, is that fair? In his book, my colleague Brad Stone chronicled the case of German kitchen knife company Wuesthof. When it stopped selling its products on Amazon several years ago, the e-commerce giant followed through on its threats to show ads for Wuesthof’s rivals. Are those good, hard-nosed business tactics — or an unfair use of Amazon’s power over shoppers?

Those are the kinds of questions to which Vestager appears to want answers — rightly. Amazon declined to immediately respond to Bloomberg News about Vestager’s comments.

Even if she finds that Amazon is harnessing information about its shopping mall sellers to the company’s own advantage, that doesn’t necessarily amount to illegal abuses of its power. And even if a company is found to abuse its market power, it may not result in a serious wound: witness what happened to Google’s parent company, Alphabet Inc.

But it’s worth noting that Vestager isn’t the only regulator or politician starting to ask hard questions about Amazon. U.S. President Donald Trump has repeatedly attacked the company for a range of perceived business abuses, U.S. politicians on the left and right have said it may be too mighty for the public’s good, and a U.S. antitrust authority is gathering information about how longstanding monopoly laws should be applied to new-economy superpowers such as Amazon.

All this sound and fury may amount to nothing. In surveys, Americans repeatedly say they hold the e-commerce giant in high regard and want to keep shopping there. But public opinion can change fast if doubts creep in about a company’s actions and motivations. Google and Facebook, for example, seem to have been hurt by accounts of their aggressive use of users’ personal information or claims that they unfairly silence conservative political views.

Vestager’s inquiry is just getting started. Wherever it goes, though, the questioning of Amazon’s power and authority isn’t going to disappear quietly.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.