Emerging-Market Rout Claims a Blameless Victim

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Whenever there’s a bout of emerging-markets flu, Indonesia catches it.

Jakarta may be crying foul, because it looked as though the nation was inoculated: Since May, Bank Indonesia has raised benchmark rates by 1.25 percentage points as insurance against the stronger dollar, almost as aggressive a move as during the 2013 taper tantrum. Meanwhile, President Joko Widodo’s government may increase import taxes and prune infrastructure projects to keep the current account in check. And the deficit on that account has improved — from 3.6 percent of GDP in 2013 to 2.4 percent now.

Yet the rupiah is down 9 percent this year, while the Jakarta Composite Index has plunged 18 percent in dollar terms.

Why is Indonesia so vulnerable? The biggest problem is the country’s addiction to overseas money to fund deficits. Foreign ownership of Indonesian government bonds grew from 33 percent in 2014 to 40 percent in 2017.

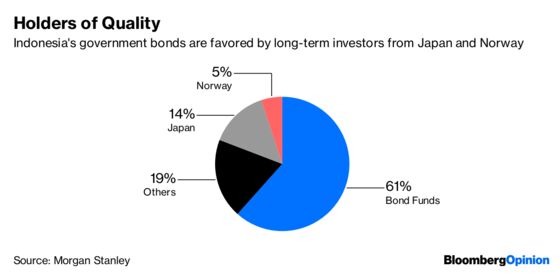

To be sure, that wasn’t just hot money. Many of the buyers of those bonds are top-quality long-term investors that don’t flee at the first sign of weakness. According to Morgan Stanley, of the $57 billion foreign investment in bonds, 14 percent was from Japan and 5 percent from Norway — with institutions so long-term in their outlook and relaxed about Indonesia’s economy that they didn’t hedge rupiah risk.

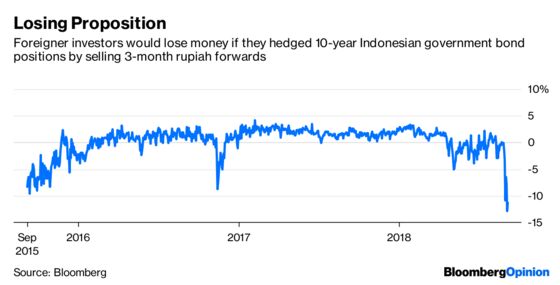

Until recently, Indonesian bonds were so desirable that hedging against a falling rupiah would have been too expensive anyway. As of July 31, 70 percent of global bond investors were overweight Indonesia, Morgan Stanley reckons, and the 10-year government bond’s spread over U.S. Treasuries shrank to a five-year low of 3.4 percentage points in early February. Buying those bonds and selling three-month rupiah forwards would have put managers in the red.

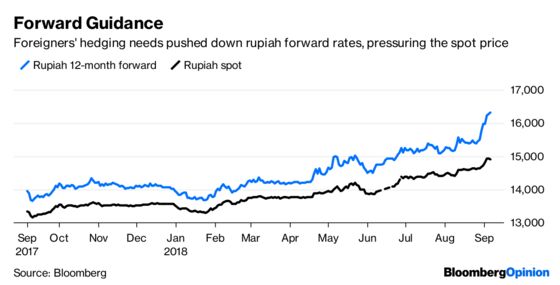

In turbulent times, however, even optimistic long-term investors need some protection from black swans. Forward rates are now implying a 12 percent drop in the rupiah over the next 12 months. If you were a mom-and-pop spot trader, you might panic and sell.

This is why strategists are unwilling to call a bottom yet for the rupiah and other Indonesian assets. It’s unclear how bad sentiment might get, how much currency hedging foreigners will seek, and therefore how much further the rupiah might fall.

Then, too, this sell-off is mild compared with the taper tantrum days. The rupiah depreciated 18 percent against the dollar in the summer of 2013. Since April this year, the devaluation has been only 6.6 percent. Some investors are indeed rewarding Indonesia’s good behavior.

Reliance on foreign capital can supercharge an emerging economy, helping it climb the global ladder. When the environment turns toxic, that effect can reverse quickly.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Paul Sillitoe at psillitoe@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.