Can Siri Teach Johnny to Read?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Convenience is atop the list of benefits Siri and Alexa have brought to millions. But is it possible that they’re promoting literacy, too?

Certainly, it’s not a benefit that immediately comes to mind. After all, we speak and Siri writes. We ask a question and Alexa enters the search terms for us. Load your iPhone up with podcasts, or ask Siri or Alexa to find you the bestseller you’ve been wanting from Audible.com, and you might never need to read a book again. With each voice-to-text improvement, we seem to be moving backward — toward a culture that relies less and less on letters or the ability to read and write.

History tells a different story. As the scope for oral communication expands, we can take comfort, and some instruction, from the variety of forms literacy has taken since its beginning in the West.

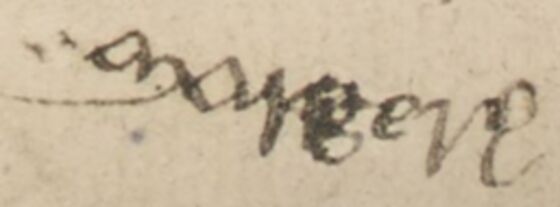

Take this signature from a letter in the 15th century:

It is not easy to see that this word is ‘Margere’ because the woman who wrote it, Margery Paston, was what we might now call functionally illiterate. Her signature was among the few words she ever put to paper, and she's clearly having trouble with her pen. But this signature also comes at the end of a long letter Margery “wrote” to her husband, and she wrote it, as she wrote many others, by summoning one of the male servants her family employed to act as a secretary. Other Paston women wrote in this way too.

This signature could be seen as a dispatch from a culture that reproduces the nightmare of Gilead depicted in “The Handmaid's Tale”: men can write and women are forbidden to because no one even teaches them how to hold a pen. But that would be a misreading: The Pastons were middle-class and so the women in the family were able to employ secretaries. Indeed, it is in these same decades that Margery Kempe used a secretary to write what is arguably the first book by a woman in English — titled, appropriately enough, “The Book of Mergery Kempe.” She could not write, but as her achievements proved, she possessed a form of literacy. She was not alone.

We might say the same thing of one of the most famous “writers” in our language, Geoffrey Chaucer. People who knew Chaucer in the 14th century liked to draw him, and there is a particularly elegant portrait of him at the front of one of the oldest copies of his masterpiece “Troilus and Criseyde.” In an important study of Chaucer from the 1970s this picture is reproduced with the caption “Chaucer Reading from his Book.” This makes sense as an interpretation of the picture. Chaucer is performing the poem before an audience. But, as was noticed more recently, he isn’t holding a book:

What this picture shows is Chaucer reciting his lengthy poem; it assumes he knew the whole of it by heart; and it provides evidence that, in the paper-poor culture in which he worked, Chaucer must have dictated this poem to his own secretary in the first place. Indeed, we know the name of at least one of these secretaries because Chaucer wrote a poem both naming him (as “Adam Scriveyn” or “Adam the Scribe”) and cursing him for his “negligence” in failing to write down accurately what Chaucer had said.

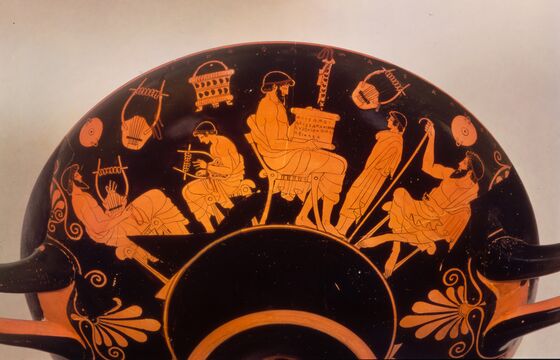

These forms of reading and writing can be traced back to the beginnings of literacy itself. On a Greek vase that survives from the fifth century BCE, just after the Greeks developed their alphabet and started writing their poetry down, there is a vivid depiction of a school scene in which boys are being taught music and letters. In the image in which the boy is being taught to “read” those letters, however, his teacher holds the papyrus away from him, so that he could not possibly see them:

Scholars of Greek culture have said that this vase depicts a stage before the reading of letters was taught in schools. And yet the depiction is also meant to tell us that the boy is literate. In the same way the boy learning music is playing his lyre, he is reciting the text. He is therefore “reading” the papyrus in every functional sense, doubtless because he committed it to memory earlier when his teacher recited it to him. Letters in this stage of Greek culture were a mode of record but probably still not the primary one. Homer, the greatest of the Greek poets, and the original “writer” of the lines on the papyrus, was preliterate; he could neither read nor write. He composed his poems by memory and sang them to an audience. He “wrote” and “read” just as Chaucer did.

Should the connection between the spoken word and literacy really be so alien to us? After all, starting in the 1950s, basic literacy training in elementary schools in the United States has involved ‘phonics.’ And what is phonics but a way of attaching written words to the sounds they had been or could become? The theory grew out of the belief that all those lines of text on the pages of schoolbooks had become too divorced from their sounds; phonics was intended to give new readers a chance to recognize written language as part of the world of language they already knew.

And that’s the point — to teach reading and writing, which is a universally accepted good. Siri and Alexa may not seem to answer any sort of pedagogical need (though it turns out they can be used to assist in the literacy training of those who are disabled or slow to learn their letters), but we would be making the common mistake if we failed to see them as helping us reach our shared aim. They are not providing a new form of literacy so much as they are letting us use a very old one in ways that produced some of the best writing we might ever hope to read.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Shipley at davidshipley@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Christopher Cannon is the Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and Classics and director of undergraduate studies at Johns Hopkins University's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.