Four Weird Tricks to Fix Australia’s Chaotic Politics

Australia, the nation famously described as “a lucky country”, looks like it’s survived another brush with ill fortune.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Australia, the nation famously described as “a lucky country, run by second-rate people who share its luck,” looks like it’s survived another brush with ill fortune.

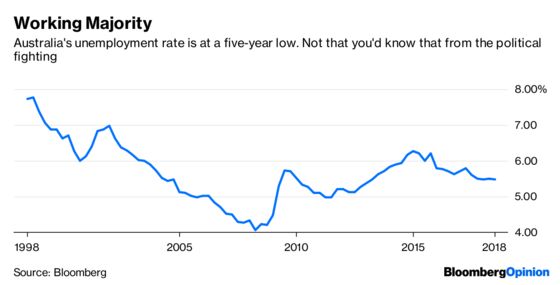

While a vote of the governing Liberal party on Friday picked Scott Morrison as the country’s sixth prime minister in just over eight years with a shaky single-seat majority in its parliament, outside of the capital there are few signs of a system in crisis. After 27 years of uninterrupted economic growth, unemployment is at a five-year low and the country is perennially near the top of international rankings for wealth, health and happiness.

Still, the 1.4 percent fall in the Australian dollar on Thursday, as a week of leadership turmoil came to a head, as well as the country’s persistent inability to set long-term policies on energy and climate, show the real cost of broken political systems. Here are four reforms that could change the set-up for the better.

Make spills harder

It’s easy to focus on the fact that the Liberal party has picked three prime ministers in as many years. There’s less comment on this: After the bloodletting in the opposition Labor party in the years when Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard fought it out, the incumbent Bill Shorten has been leader of the opposition for more than five years, a feat achieved by only one other Australian politician in the past half-century.

That’s not so much a testament to his political skills — it’s only a month since the media were full of rumors of a challenge from shadow transport minister Anthony Albanese. Rather it’s a result of one of Rudd’s last acts in 2013, when the party passed rules lifting the share of elected members needed to overturn the leadership from 50 percent to 60 percent, and 75 percent when the party is in government. If Morrison has any sense, a similar move will be one of his first acts as prime minister.

Have more MPs

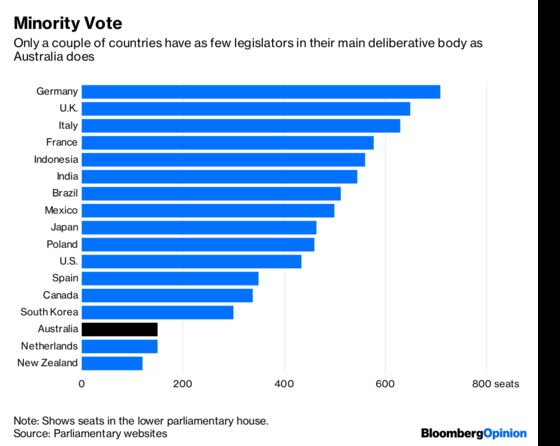

Australia is unusual in having a relatively small parliament. Its governing House of Representatives has just 150 members, well below the numbers in most other advanced democracies.

That has a couple of effects. For one thing, it makes party coups relatively easy: Plotters only need a short round on the telephones to assemble the 45-odd votes needed to remove a leader, compared with the 150 or more that were needed to replace Margaret Thatcher under the U.K. Conservative party’s superficially similar system.

A small House also puts leading legislators in a pressure cooker. Fully 42 of the 107 representatives and senators in the governing Liberal-National coalition were members of Turnbull’s ministry, meaning most of the half-way competent politicians are already in the cabinet. While in the U.K. parliament intra-party ideological disputes are worked out between the cabinet and committees of backbench MPs, in Australia this happens within the cabinet itself, leading to occasional blow-ups of the kind we just saw.

Sort out the Senate

Elections for Australia’s Senate are notoriously complicated: Ballot papers can be as large as bath towels, and the ranked-voting system often produces perverse results thanks to the way parties are allowed to trade preferences to hand seats to candidates with little support of their own.

Australians seem to like the fact that governments hardly ever win a majority in the Senate, allowing cross-bench politicians to push legislation in a more moderate direction. However, the Senate’s voting system means the fulcrum typically no longer sits with a group with a well-defined agenda, but with fissiparous personality cults and chancers, who are often all but unknown until the moment they’re elected.

Thanks to the strong party system, the Senate rarely fulfills its intended purpose of providing a unique voice for Australia’s states and territories. A nationwide party-list proportional representation system would preserve the rights of minor parties while ensuring the make-up of the chamber more closely reflected voters’ intentions.

Longer, and shorter, terms

Elections for Australia’s House of Representatives happen every three years. The Senate is elected every six, with half of senators going to the polls at each House election.

One negative effect of this is that views in the parliament rarely change as fast as those among the electorate. Even after a thumping electoral victory, the half of the Senate that’s been in parliament for three years can hold up legislation, preventing the government from delivering on its promises.

Meanwhile, the House is driven by short-termism and an obsessive eye on opinion polls. The “30 Newspolls” test that has in its way contributed to the fall of two consecutive prime ministers would be meaningless in a democracy where 30 months was not so close to the full term of a parliament.

Switching to four-year terms, as all but two of Australia’s states and territories have done, would allow representatives to get on with the business of governing and ensure the composition of the Senate reflected the intentions of the electorate.

How to do it?

None of these changes would be easy. The first two could be adopted without changing the constitution, however. Even for the other two, Australia isn’t short of unfinished business on issues such as becoming a republic, establishing a First Nations body to advise parliament, and sorting out troublesome constitutional provisions governing the eligibility of federal politicians and the ability of the government to make laws for specific races.

An omnibus referendum to deal with all that is long overdue. If only there was a prime minister with the mandate to propose it.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Paul Sillitoe at psillitoe@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.